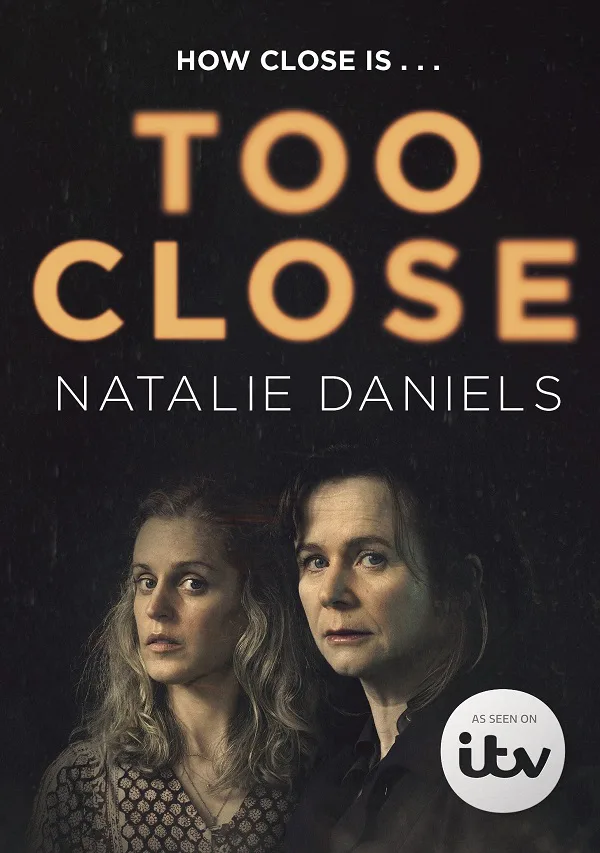

Female relationships as a cat-and-mouse game have emerged as a reliable source of buzzy series, and AMC+ original miniseries “Too Close” throws itself into the ring with a setup now familiar for this subgenre. The trend fueled by programs like “Killing Eve,” “The Secrets She Keeps,” and “Losing Alice”—one about a female detective trailing a female assassin; one about a baby-crazy woman stalking an influencer; and one about the parasitic relationship that develops between a film director and screenwriter—tends to position women as competitive with each other, maybe a little bit attracted to each other, and sometimes unable to separate themselves from each other. “Too Close” treads the same ground, and although the performances from lead actresses Emily Watson and Denise Gough are strong, the circumstances that swirl around them are so predictable that they threaten to overwhelm the impact of that central duo.

The fundamental issue is a disconnect between the show “Too Close” initially presents itself as and the show it ultimately reveals itself to be. “Too Close” first presents as a neo-noir/thriller hybrid, with young, attractive mother Connie Mortensen (Gough) accused of attempting to murder her daughter and another child. Was she in her right mind when she drove her SUV over a bridge and dropped them all into a river? Could she stand trial? Or were her actions driven by mental illness, which would mean a lifetime in a psychiatric facility?

“Too Close” sets up those questions in the first episode of three (all to be released on May 20 on AMC+), and then splits its time between Connie and Dr. Emma Robertson (Watson), the forensic psychologist assigned to Connie’s case. As Emma tries to get Connie to open up so she can assess Connie’s state of mind in her court-required report, the two women find they might have more in common than they expected—but “Too Close” is uneven in its attentions. First the women are at each other’s throats, which supports the miniseries’ initial neo-noir/thriller leanings. Then they’re sharing raw, personal details and empathetically connecting over life’s mistreatment of them, which takes “Too Close” out of genre territory and more into the space of a routine investigative drama. You could mistake the third episode’s final 20 or so minutes for a fairly standard episode of “Law and Order.”

That’s not to say that what Emma and Connie connect over—frustration with a world that doesn’t see them, with men who took their best years from them, and with ambitions and friendships that feel irretrievably stalled—isn’t relatable and recognizable. But how writer Clara Salaman (adapting her own novel, published under the pseudonym Natalie Daniels) and director Susan Tully formulate the surrounding characters whose actions drive the reactions of Connie and Emma leaves much to be desired. With those characters so underdeveloped but the effects of their actions so outsized, “Too Close” fails to hit quite the right tonal balance that would really convince us of the ways that Emma and Connie’s relationship transforms.

“Too Close” begins with a horrifying act, given appropriate tension and horror by Tully’s claustrophobic direction: On a rainy night, a clearly frantic Connie drives her SUV, with her daughter Annie (Isabelle Mullally) and her neighbor’s daughter Polly (Thea Barrett) in the backseat, onto a bascule bridge. As the flashing red light indicates that the bridge is separating in the middle, Connie punches it—ramming through a dividing barrier and sending the car into the river below. After she is pulled out (horrendously bruised, but not devastatingly injured) and both children are rushed to the hospital (where they’re placed in comas, their health precarious), Connie becomes known as the “yummy mummy monster,” and her case receives national attention. Emma, a forensic psychologist, takes the case after she ignores her husband Si’s (Risteard Cooper) reservations. Her task is to determine whether Connie’s amnesia is genuine, and so she records their meetings to revisit later. What was Connie’s relationship with Ness (Thalissa Teixeira), the beautiful new neighbor who becomes Connie’s best friend, who mimics her tattoos and her perfume, and who ingratiates herself into the lives of Connie and her husband Karl (Jamie Sives)? What about when Ness’ wife left her and their daughter Polly, and Connie realized that maybe she didn’t just care deeply about Ness—maybe she was actually falling in love with her? How did that make Connie feel?

Connie, meanwhile, doesn’t take Emma’s questions lying down; instead, she instigates a battle for dominance with lengthy monologues about the unhappiness she senses in Emma as well. Gough, who elevates the material given to her by markedly differentiating between the Connie of before with the Connie of now, spits out barb after barb with measured relish. Do Emma and Si still have sex? Is Emma happy in her job? Does Emma have children? Does she love them? “You can be very tedious, Connie,” Emma says, but aren’t the questions Connie is asking her really clues about Connie herself?

The problem with this tête-à-tête dynamic between Emma and Connie, though, is that when “Too Close” incorporates flashbacks for Connie or present-day scenes for Emma, the narrative often relies on its characters acting, frankly, absurd. The instigating events to which Connie reacts are so illogical and so lacking in realism that watching certain scenes becomes irritating rather than illuminating. (Other issues: that the series’ only Black or women of color characters are uniformly portrayed as duplicitous, cruel, or negligent, and that characters’ sexual preferences and potential queerness feel primarily like “gotcha!” moments.) Emma’s character, and the subplots that drive her, fare better, and Watson impressively wields a number of unimpressed, numb, and aghast expressions: after her friends’ gossipy reaction to Connie’s case, after a dutiful and unsatisfying sex scene with her husband, and after a harrowing conversation with Connie’s confounded father.

It’s a testament to Watson’s skill that she so naturally communicates the self-destructive impetus for so many of Emma’s choices: her constant smoking, her midday drinking, her hitting “ignore” on her cellphone when her husband calls. When “Too Close” reveals itself as more of a tragedy than a thriller, Watson serves as the narrative’s belabored center, and the scenes she shares with Gough are the miniseries’ strongest. The answers to Connie’s bitter “What could possibly go wrong in your perfect world?” query toward Emma aren’t particularly unique for stories like this, but Watson and Gough meet at a certain wavelength that works well enough for the series’ three episodes. Although “Too Close” struggles to find the right balance between the demands of its plot and the depth of its characters, its most impactful moments are found when Connie and Emma—women of different ages, backgrounds, social classes, and lifestyles; women who have both done horrible things while overwhelmed by the emotional and domestic labor that so commonly falls to their gender—realize that the forgiveness they’re seeking from others needs to start with themselves.

“Too Close” is available in its three-episode entirety on AMC+ on May 20.