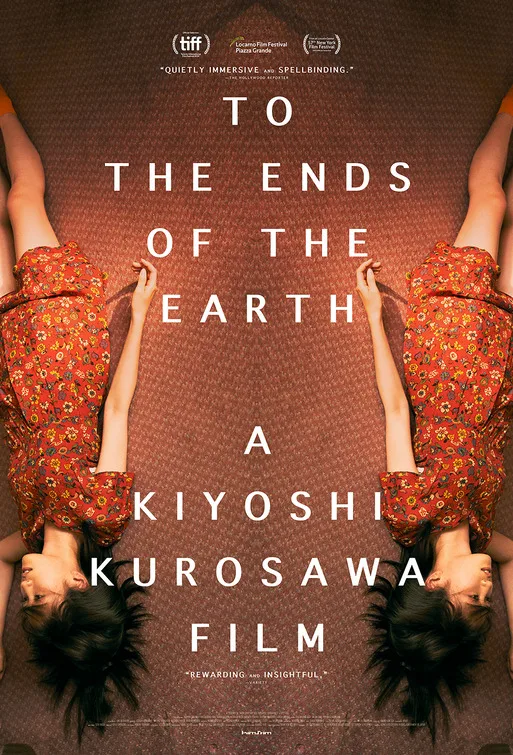

How to describe “To the Ends of the Earth”? I could tell you that it’s an extraordinary character study: Yoko (Atsuko Maeda), a young Japanese TV journalist, travels to Uzbekistan on assignment, and gradually spirals into an emotional crisis after a series of touch-and-go misunderstandings remind her that she’s a single woman abroad, working a job that requires her enthusiasm, but doesn’t really value her input.

I could also tell you that “To the Ends of the Earth” is a movie where gorgeously lit and framed exterior photography, as well as consummately precise body-language-centric performances, often convey more than most dialogue could. This is the sort of arthouse drama that’s complimented in its press notes with praise for director Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “mise en scene,” or the arrangement of objects within the camera’s frame. Trying to explain how this movie works as well as it does, without using excessive jargon or some kind of audiovisual aide, is tricky since “To the Ends of the Earth” isn’t about anything less than its heroine’s uncertain relationship with her foreign environment, and what she chooses to communicate simply by being seen and heard. Which is often thrilling to behold, but not so much to explain.

Still, I’ll give it the ol’ college try. You can almost always understand what’s happening to Yoko without ever really knowing what she’s feeling since Maeda’s character doesn’t often explicitly spell things out through literal-minded dialogue or canned confrontations. Yoko’s behavior suggests that she’s “cautious and insular like many young Japanese,” as the movie’s press notes spell out: she keeps to herself when she’s not on call, enjoys texting her firefighter boyfriend Ryo (never seen or heard), and sometimes takes short side-trips by herself.

And when Yoko is on the job, she’s often tamping down her emotions for the sake of performing as an enthusiastic, engaged travel host. She smiles and remarks about the “crunchy” flavor of uncooked rice in a bowl of “plov,” a local dish—the chef didn’t have time to properly cook the rice before an unannounced shoot—and pretends to casually shake off intense nausea after she takes three consecutive turns on a fun-park pendulum ride (the camera crew couldn’t get enough B-camera footage of Yoko’s face after just one or two takes).

Yoko also studiously avoids men and other locals when she sneaks out of her hotel room to get food or sight-see. Her mind sometimes wanders, like when she visits a concert hall, and she fantasizes about performing on stage with a small orchestra sitting in front of her. The staging, lighting, and pacing of this unusually whimsical sequence (it’s all a dream!) reveals its character: the camera follows Maeda from behind in medium close-up as Yoko enters and prepares to exit a series of rooms that are decorated with gorgeous arabesques at the end of each hallway. In this scene, Yoko is never shown leaving a room; she approaches the end of one hallway, and then re-appears at the far side (or in the middle) of another room. She finally appears on stage, and sings a moving version of Edith Piaf’s “Hymne a L’Amour.” The theater’s stage seems broad enough that the orchestra pit below appears to us like the outside of a zoo cage; for one rare moment, we are on the inside with Yoko looking out.

Thankfully, the rest of “To the Ends of the Earth” is not as impersonal or cold as that last line might suggest. Environmental ambience often trumps story in Kurosawa’s films, as he explained to me when we talked about his appropriately titled “Creepy.” Fluid camerawork, subtle lighting cues, and a rich depth of field make each scene a pleasure to look at thanks in no small part to Kurosawa and regular collaborator/cinematographer Akiko Ashizawa. Sound designer Kenji Shibasaki’s subtle, but instrumental contributions to the movie’s densely layered soundtrack are also noteworthy.

All of this consummately pared-down style brings things back to Yoko, who internalizes so much that when she does ultimately try to express herself, it’s understandably not an intuitive process. She tries to free an underfed goat during an improvised travel segment, but only winds up leading the poor animal to its doom (There are wild dogs in the area, and the animal’s neglectful owner has to be paid to stay away). There’s also some discussion about what the sea symbolizes, though it’s ultimately inconclusive: “I hear it’s a dangerous place. Nothing to do with freedom.” This line is especially funny given how deeply felt and often stunning “To the Ends of the Earth” is as a days-in-the-life portrait of a young woman who’s struggling to enjoy her own freedom. That sentiment may be hard to explain in the abstract, but Kurosawa and his collaborators make it easily understood.

Now playing in virtual cinemas.