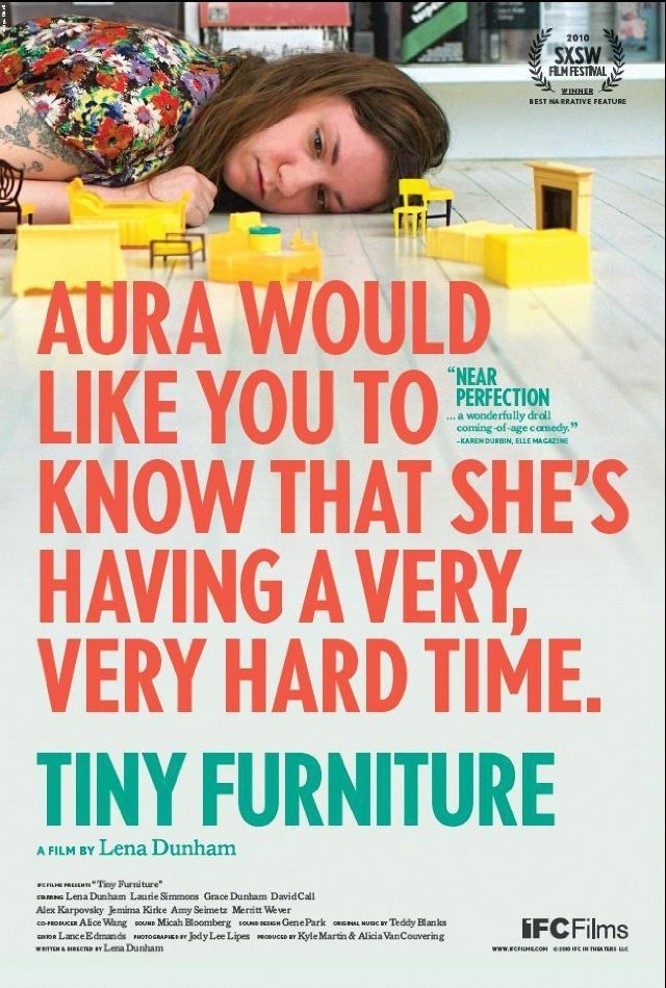

There is a strange space between when you leave school and when you begin work. You are idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean. You grow restless. You cannot go back and are uncertain how to proceed. “Tiny Furniture” is about Aura, who is becalmed on that sea.

She has graduated from college in Ohio, and returned home to live in her mother’s loft in Tribeca. Her boyfriend called it quits; he had to return home to Colorado and see about the spirits of his ancestors, or something. Four years of education have left her with one video on YouTube and the ability to show approval when a guy says he’s reading The Road by Cormac McCarthy. Her mother is a famous artist who makes a lot of money selling photographs of tiny furniture, sometimes in the same frame as the feet and legs of Nadine, Aura’s sister, who is taller, thinner and younger than Aura.

Aura (Lena Dunham) is discontented. She hates living at home but has no money to move out. She wants a good job but takes one taking reservations at a restaurant. She wants love and acceptance, and finds it much diluted by her distracted mother (Laurie Simmons) and her competitive sister (Grace Dunham). Of possible boyfriends there are: (1) Jed (Alex Karpovsky), a “big deal on YouTube,” who rides a mechanical pony while reciting Nietzsche, and (2) Keith (David Call), who works at the restaurant and has a girlfriend but asks Aura out and then stands her up.

Aura’s life unfolds without plot because there is none. The film seems deliberately motionless, although deep currents are stirring. We see Aura at home, with Jed and Keith, and with her new friend, Charlotte (Jemima Kirke), who has a British accent, lends her clothes and otherwise seems firmly one-up. None of these characters have what you might call chemistry, and that seems deliberate. This is a movie about people who are all passive-aggressive, including Aura. Nobody laughs or tries to say anything funny, and when Aura is happy sometimes, she doesn’t trust it.

Aura is played by Lena Dunham, who wrote and directed the film. Her mother and her sister are played by her real mother and sister. The loft in Tribeca is where her family lives. I have no idea if they’re playing themselves, but they’re certainly convincing. Dunham, indeed, plays one of the most real people I’ve seen outside of a documentary. She and the others are unaffected, behave as people we know actually do, live in familiar rhythms.

Visually, the film is simple and direct, as unadorned as the white cabinets that cover a wall of the loft. Dunham’s cinematographer, Jody Lee Lipes, doesn’t move the camera. It’s locked down for a steady, flat gaze. This is correct. It sees like Aura sees. She regards with detached fascination as people behave as people will. Her personality doesn’t suggest tracking shots.

Why do I feel such affection for “Tiny Furniture”? It’s a well-crafted film, for one thing. For a first picture, it shows a command of style and purpose; Dunham knows what she wants and how she needs to get it, and succeeds. Her character Aura is not charismatic or glowing or mercurial or seductive or any of those advertising adjectives, but she believes she deserves to be happy, and we do, too.

The movie has a scene in which sex is enacted. It isn’t great sex. It calls into question Woody Allen’s statement that the worst sex he’d had wasn’t that bad. It happens unexpectedly between two people. It happens in the most depressing place for sex I can imagine. No, worse than whatever you’re thinking. It is so desperately dutiful. Two people become seized with the urgent need to create an orgasm together and succeed, and that exhausts the subject. The scene and what leads up to it define Aura and her partner in terms of what they will settle for. Sometimes that’s better than nothing.

I know what the budget of this movie was, but never mind. Lena Dunham had every penny she required. She also had all the talent she needed, and I look forward to her work. It’s hard enough for a director to work with actors, but if you’re working with your own family in your own house and depicting passive aggression, selfishness and discontent and you produce a film this good, you can direct just about anybody in just about anything.