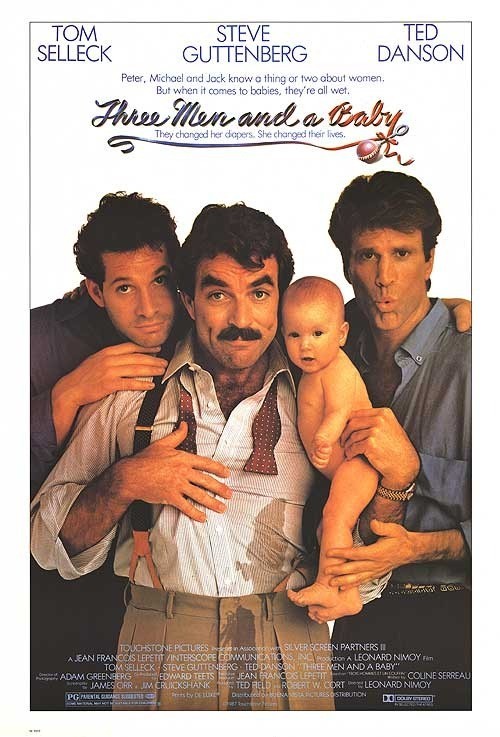

“Three Men and a Baby” begins with too many characters and too much plot, and 15 minutes into the film I was growing restless. It spends a lot of time describing the lifestyles of three bachelors – Tom Selleck, Steve Guttenberg and Ted Danson – who share a luxury apartment and play host to a never-ending stream of girlfriends. We meet too many of the girlfriends, and too many of their friends. And then it’s the morning after Selleck’s big birthday bash, and on the doorstep outside their apartment is a basinette containing a little baby named Mary. From that point on, the movie finds its rhythm, and it works.

The baby apparently was fathered by Danson, an actor who has just left to spend 10 weeks shooting a film in Turkey. Selleck and Guttenberg contemplate the little bundle with dread, and Selleck’s confusion is not helped when he goes to the market to buy baby food and gets a lot of advice about babies from a helpful clerk. (“You mean you don’t even know how old your baby is?” she asks incredulously.)

Shortly after comes one of the funniest scenes in a long time, as Selleck and Guttenberg, an architect and a cartoonist, try to change Mary’s diapers. The basic situation may sound familiar and even overworked, but the way they act it and the way Leonard Nimoy directs it, it builds from one big laugh to another.

The movie never steps wrong as long as it focuses on the developing love between the two big men and the tiny baby. At first they’re baffled by this little bundle that only eats, sleeps, cries and makes poo-poo – lots and lots of poo-poo. “The book says to feed the baby every two hours,” Selleck complains, “but do you count from when you start, or when you finish? It takes me two hours to get her to eat, and by the time she’s done it’s time to start again, so that I’m feeding her all of the time.”

Those scenes are the heart of the movie. Unfortunately, there is also a completely unnecessary subplot to distract from the good stuff. “Three Men and a Baby” is a faithful reworking of a French film from a few years ago, in which the basic plot device was that two “packages” were left with the bachelors on the same day – a baby, and a fortune in heroin – along with the message that “the package” would be picked up a few days later.

The plot allows them to know nothing about the heroin, so they think the “package” is the baby, and that leads to a misunderstanding with some vicious drug dealers.

Learning that an American remake of the French movie was being planned, I assumed that the drug angle would be the first thing written out of the script. To begin with, it’s completely unnecessary; the fact that the baby is left on the doorstep is all the story needs to get under way, and the central story is so funny and heartwarming that drugs are a downer.

But, no, Nimoy and his writers, James Orr and Jim Cruickshank, have remade the entire French movie, drugs and all, leading to a badly staged and distracting confrontation between the heroes and the dealers at a construction site.

Why bother with all the exhausted apparatus of crime and violence, recycled out of TV crime shows, when the story of the men and the baby is so compelling?

Luckily, there’s enough of the domestic comedy to make the movie work despite its crasser instincts. One of the big surprises in the movie is Selleck’s wonderful performance as the bachelor architect. After playing action heroes on TV and in the movies, he now reveals himself to be a light comedian in the Cary Grant tradition – a big, handsome guy with tenderness and vulnerability. When he looks at baby Mary with love in his eyes, you can see it there, and it doesn’t feel like acting.

Because of Selleck and his co-stars (including twin baby girls, Lisa and Michelle Blair), the movie becomes a heartwarming entertainment. There are, however, a couple of glitches at the end. When Mary’s mother turns up, the men allow her to leave with the baby without even asking the obvious question on the mind of everyone in the audience: How could she have abandoned the baby in the first place? Another problem is that Selleck isn’t the only one who doesn’t know how old Mary is. If you follow the various dates mentioned in the script, the filmmakers also haven’t a clue. But by the time the movie reaches its predictable but comfortable ending, who cares?