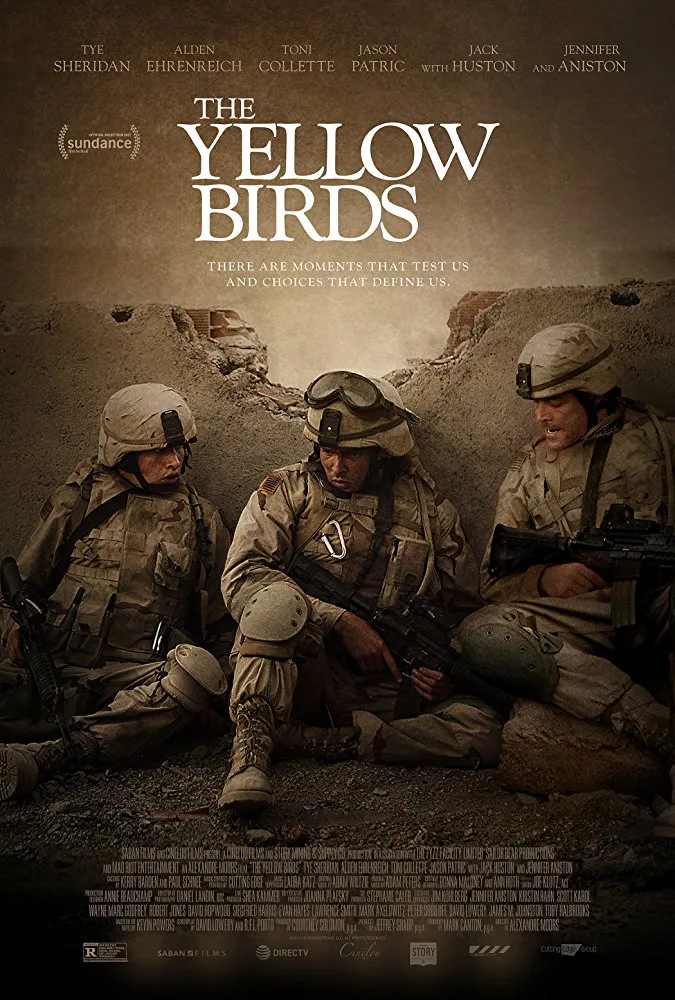

Some pulse-pounding battle scenes and strong work by two very appealing young actors, Alden Ehrenreich and Tye Sheridan, give the Iraq War drama “The Yellow Birds” a measure of distinction. Yet Alexandre Moors’ film is also so lacking in anything new or compelling to say—either emotional or political—about its subject that it ends up a rather dispiriting slog of a movie.

The film starts out with some night warfare amid palm trees that, like later scenes, recalls the incendiary vividness of Kubrick’s “Full Metal Jacket.” Soon enough, though, the story’s time-shifting commences and we’re back at basic training, where two soldiers meet in the barracks. Daniel Murphy, a.k.a. Murph (Sheridan), age 18, approaches 20-year-old Brandon Bartle (Ehrenreich) because he’s heard they’re both from Virginia. While that doesn’t overly impress Bartle, who’s not the friendliest sort, they start talking and reveal some of the differences that separate them: Murph’s a middle-class kid who wants to attend the University of Virginia when his service is done, Bartle a lower-class guy who really doesn’t know what he wants.

Despite these differences, Murph’s puppyish innocence brings out a protective instinct Bartle, and a soldierly friendship is born. Before they ship out for the war zone, there’s a party that involves the men’s families, and there Bartle meets Murph’s mom Maureen (Jennifer Aniston). A worrying sort, she takes Bartle aside and makes him promise that if anything happens to her son, he’ll bring her the news personally. While this rather too obviously telegraphs what’s to come, it gives Bartle an added bond with Murph.

Once they’re in Iraq, the perils facing the men quickly become evident. Although we’ve seen the same techniques in many Iraq War movies by now, Moors (“Blue Caprice”) does a skilled, effective job staging the scenes of urban fighting with handheld cameras and the kind of editing that emphasizes the disorientation and terrors that arise when the danger seems omnidirectional. And when death first occurs right in front of Murph’s eyes, his shock is almost palpable.

There is, here and later, no allusion to the war’s geopolitical context, nary a single mention of Saddam, George W. Bush or any of the debate back home; and needless to say, the only injuries or deaths that count for anything are those of Americans. All of this would be less regrettable if it weren’t such a big cliché at this point, the default position of most Iraq War movies. You’d think filmmakers like Moors would throw in some discussion of the war’s politics if only to give such stories some authentic detail of the time. (The Iraq scenes, incidentally, were shot in Morocco.)

This story takes a crucial turn when we’re suddenly back in Virginia with a battle-scarred Bartle and the whereabouts of Murph are a mystery. The older soldier turns zombie-like, sleeping all day, downing endless six-packs of beer and fighting with his angry, uncomprehending mom (Toni Collette). As he’s also pursued by a CID officer (Jason Patric) and Murph’s mom, who wants him to make good on his promise, the tale begins recurrent flashbacks to Iraq in unraveling the truth of Murph’s fate.

There are no spoilers here, but the mystery’s revelation feels inordinately protracted and results in a conclusion that seems paltry, unsurprisingly depressing and not wholly credible. Why? “The Yellow Birds” (maybe I missed something, but I never figured out what the title means) was adapted from a well-regarded novel by Iraq veteran Kevin Powers. The commentary I’ve read about the book suggests a familiar occurrence: A novel attracts filmmakers due to its interesting characters, smart prose and highly-charged incidents, but when screenwriters—in this case, David Lowery and R.F.I. Porto—adapt it, they put it in dramatic form but fail to make it compellingly cinematic.

As noted, the film’s unquestionable assets are its two young leads. Both are very skilled performers and show their abilities especially in scenes where the soldiers are embroiled in traumatic, potentially lethal situations. While Sheridan’s Murph is skittish and appropriately vulnerable to war’s horrors, Ehrenreich’s Bartle—who has the movie’s most screen time and longest character arc—persuasively transforms from a green, unmoored kid into a haunted and very damaged man.

It’s too bad this film doesn’t ultimately give these actors a better showcase, but fear not, that shouldn’t hurt their careers: sci-fi franchises aside, both seem likely candidates for stardom.