“The Workers Cup” is a documentary with a defeated spirit, but with fleeting glimmers about why the oppressed keep playing.

It tells of the migrant workers from countries like Nepal, India, Ghana, and Kenya who are building a new stadium for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. These men have taken up such dehumanizing labor for these monstrous companies because it offers a pay better than a job in their own country. It’s still not much of a salary, and they live in cramped, dirty labor camps away from their families. Many of them work an illegal amount of seven days a week, and talk about freedom as if it were a dream. But at the end of their shift, they get to play soccer with their co-workers, against other companies, as part of a tournament called the Workers Cup. The name of their employing company is the also the name of their team.

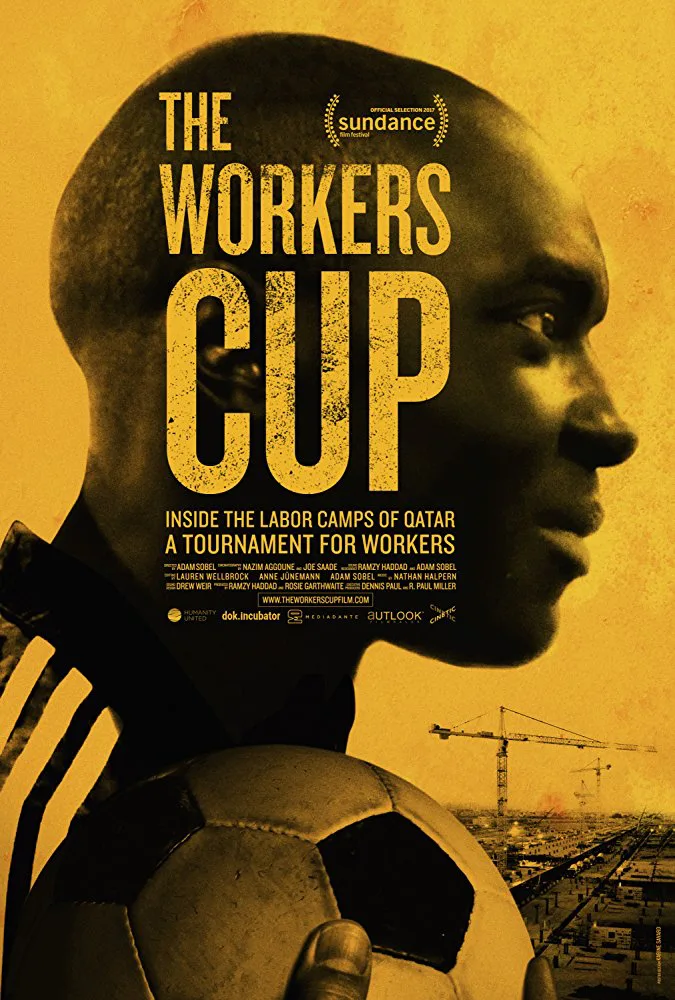

Filmed 87 months before the start of the World Cup, director Adam Sobel’s movie has no sentimentality for this shiny monstrosity that is slowly being built, among other towering buildings in Qatar. He is acutely focused on exposing the poor quality of life of the workers, and the bittersweet escape that playing soccer provides at night. There are some excellent players, like a man named Kenneth who receives a special bonus from his company GCC, but he is another cog in this machine. “The Workers Cup” has incredible access to these workers and their personal thoughts in brief interviews, leading one to wonder what kind of agreement these companies had with Sobel, or if they were ever afraid of his documentary crew.

The footage captured makes for frustrated and frustrating journalism; it surely captures the non-glamorous side of this massive project, and it offers a series of portraits for men who would be otherwise faceless. But the ultimate points it makes are not challenging enough themselves. “The Workers Cup” sings a timeless refrain about the disparity of class, and the dehumanization of a work force in service of a massive business.

This is modern-day slavery, the movie points out directly. The quality of life in this work atmosphere is especially shown in what these men think of their self-worth: “It’s for the good of my children that my own life is thrown away,” one man says, after sharing that he works in security for a luxurious mall, but isn’t allowed to walk around after 10 AM when it opens. “You don’t get to have the privileges of life,” another man states. There’s a stirring moment at the end, a speech from a coach, a rally cry: “We are not slaves,” he declares to his room of athletes. In a narrative movie, it would lead to some kind of uprising. Here, they are then shown getting back to playing soccer, doing something for themselves that is ultimately good company PR.

Sobel paints a wider-ranging picture of their situation’s ugliness, with abrasive edits from the luxurious towers and sports cars to the wide-ranging streets of poverty. His camera, not prodding, captures one injured worker telling another about how someone cut his leg, just so the assailant could be sent home. Another athlete talks of coming from Ghana to make money as a soccer player, and send money back to his father: “If this is hell than I’d rather be in hell than in heaven in Ghana.” It’s a big contrast of personal stakes compared to when Sobel talks to those who work in the offices. Employees openly share that soccer games help the companies make more money, and are even used to recruit more workers.

The men in this movie speak about wanting to be taken seriously as soccer players, and Sobel does provide them some star-athlete moments, like when he gets his cameras right there on the field for penalty kicks. His editing doesn’t create a sports movie-friendly arc with teams or their tournaments, but he’s right in the middle of the fleeting euphoria of sideline celebrations, the happy jigs and exclamations. A sense of universal excitement emerges, and so does a purity for a sport that transcends language and class, and just needs a ball, bodies, and some goal posts. These passages feel like they have an idea as to what leads to a peaceful coexistence: camaraderie, treating your fellow human beings as equals, and stealing what pure happiness you can.

On a larger scale, “The Workers Cup” is not meant to be viewed in a vacuum. It has uncanny timing as our current nation deals with the issue of whether athletes must stand for the national anthem, one that connects here to the worth of these athletes and the companies that use their bodies and talent in any way possible. “Shut up and play,” the sentiment goes. But compared to the activism of players like Colin Kaepernick or the resilience of the Philadelphia Eagles, the men in Sobel’s film don’t even have a voice to be silenced. You’ll be grateful that Sobel’s efforts try to change that.