She thinks of everything: where his glasses are, when it’s time to take his pills, what he should eat for lunch. After three-plus decades together, the wife anticipates the husband’s needs and meets them before he even realizes he has them—and certainly long before she’d ever consider tending to any needs of her own.

It’s an efficient if unhealthy dynamic that’s kept their marriage humming along through two kids and a grandkid on the way, through bouts of infidelity, through the husband’s spectacular and longstanding literary success and up to his crowning achievement: winning the Nobel Prize.

This should be a joyous occasion for them both, a chance to take a breath and assess with pride the life they’ve built together. Instead, it becomes an opportunity for the wife to confront some uncomfortable, deeply suppressed truths.

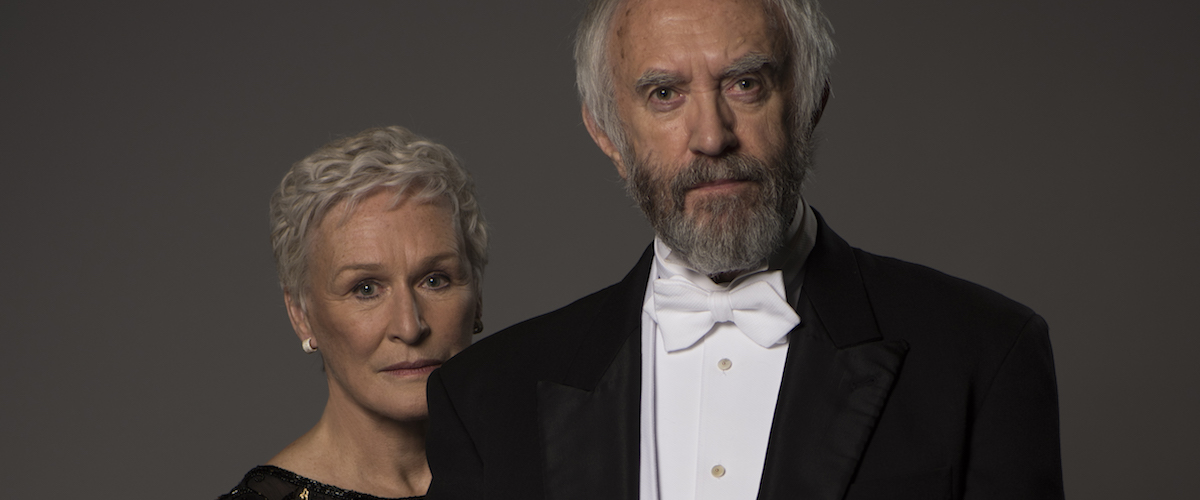

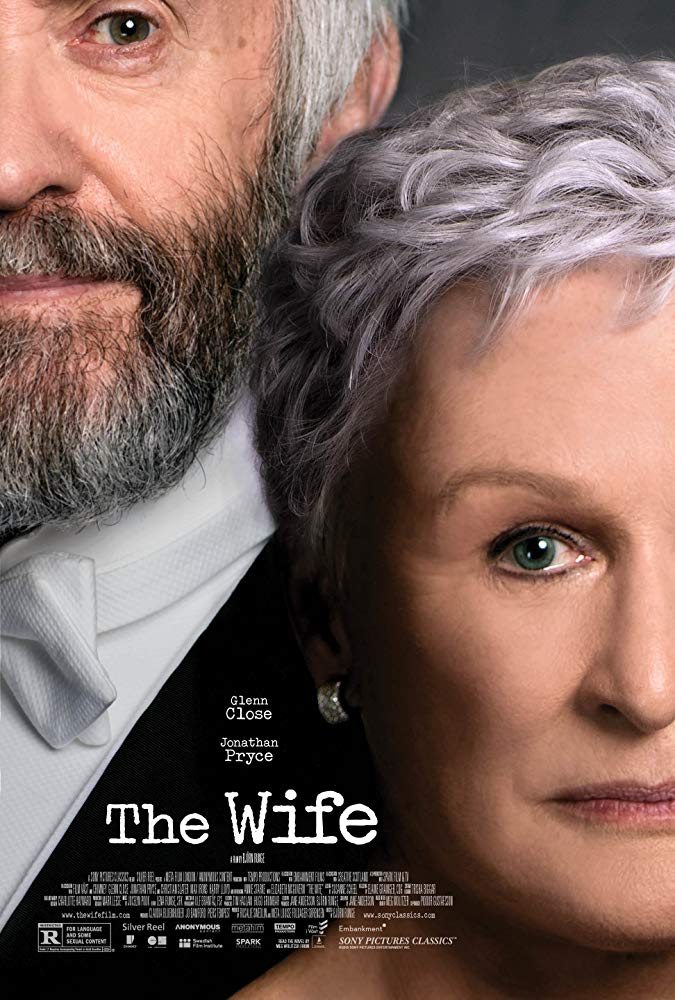

That process of achieving clarity is riveting to watch over the course of just a couple of days in “The Wife.” And as the title character, Glenn Close is subtly devastating, indicating a lifetime of repression and resentment in just the slightest wry smile or withering glance. Close and Jonathan Pryce have crackling chemistry with each other, the two veteran actors enjoying snappy banter and enduring lacerating battles. But while Pryce’s character remains steady in his narcissism and neediness, Close’s undergoes a quietly powerful transformation from self-deprecating spouse to fiery force of nature. The sort of scenery-chewing scenes Close is known for seizing upon take a while to arise, and when they do, they are doozies. But watching the steady build-up to her character’s epiphanies provides a different kind of pleasure.

Swedish director Björn Runge’s approach is no-nonsense and workmanlike, perhaps to give these esteemed actors room to swagger and shine, but a bit more imagination and artistry wouldn’t have hurt. (“The Wife” is also distractingly, flatly bright.) Working from a script by Jane Anderson, based on the novel by Meg Wolitzer, Runge jumps back in time here and there to provide context for the relationship we see at the film’s start.

It’s 1992 in wealthy coastal Connecticut. Pryce’s Joseph Castleman is awake in the middle of the night, unable to sleep out of nervous anticipation that he might get the call he’s been waiting for from Stockholm. When it finally comes—with the giddy news that he’s this year’s recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature—his first instinct is to have his wife, Joan, join them on the line from another phone. She is there to support him, as she always has been, as we’ll learn in vivid and increasingly dramatic detail.

A celebration at the couple’s sprawling home further reveals nuances to their relationship. Joe is holding court with his accomplished, adoring guests; Joan is holding a tray full of champagne flutes to serve them. Their grown son, David (Max Irons), an aspiring writer himself inspired by years of bitterness toward his brilliant old man, is quick to point out this disparity.

“I don’t think people give the spouse enough credit,” says Christian Slater, who adds a layer of tension as the sly, would-be biographer trying to insinuate himself into this momentous occasion. But shy Joan, who always looks just right and says just the right thing, is loath to claim any such credit. She doesn’t even want the greatest American writer of his generation to thank her on the world stage.

“I don’t want to be thought of as the long-suffering wife,” she tells Joe as he ponders what to say in his acceptance speech. Once they reach Stockholm, she also doesn’t want to take part in the shopping trips and beauty treatments offered to the Nobel winners’ spouses – all wives, by the way. Awkward interactions between the best of the best in their respective fields provide moments of absurd humor in this rarified setting, as do the many over-the-top displays of adulation. And yet, there’s a simmering undercurrent of unease as Joan’s disquiet swells.

We see the roots of that independent streak in flashbacks to Smith College in 1958, when Joan (Annie Starke, who nicely mirrors Close’s cadence and mannerisms) was a bright student with great promise and Joe (Harry Lloyd) was her charismatic professor – with a wife and an infant daughter at home. Even then, though, we can see her silently listening, taking it all in, reflecting her inner analysis only in slight, tantalizing ways.

“The Wife” gets juicier and juicier as Joan eventually gives voice to all she’s seen and done and unleashes secrets she’s held close for too long. Once she does that, she can finally allow herself to come into her own—and the look on Close’s finely featured face at the finale suggests she’s ready to do just that with a vengeance, and on her own terms. It’s a moment of understated triumph.