Something is wrong in the village. Some malevolent force, some rot in the foundation. This wrongness is first sensed in a series of incidental “accidents.” Then the maiming of a child takes place. This forces the villagers, who all know one another, to look around more carefully. Is one of them guilty? How can that be? One person couldn’t be responsible for all of these disturbing events. Have many been seized in an evil contagion?

After the first screening of Michael Haneke’s “The White Ribbon” at Cannes, everybody had theories about who “did it.” Well, we’re trained to see such stories as whodunits. Haneke is never that simple. It all may have been “done,” but what if there seems to be no doer? What if bad things happen to good people who are not as good as they think they are? In Haneke’s “Cache” (2005), who shot the alarming videos spying on the family? Are you sure? Haneke’s feeling is that we can never be certain.

This great film is set in rural Germany in the years before World War I. All has been stable in this village for generations. The baron owns the land. The farmer, the pastor, the doctor, the schoolteacher, the servants, even the children, play their assigned roles. It is a patriarchal, authoritarian society — in other words, the sort of society that seemed ordinary at that time throughout the world.

We are told the story many years after it took place, by the schoolteacher (Ernst Jacobi). In the film, we see him young (Christian Friedel). The old man intends to narrate with objectivity and precision. He’ll draw no conclusions. He doesn’t have the answers. He’ll stick to the facts. The first fact is this: While out riding one morning, the doctor (Rainer Bock) was injured when his horse stumbled because of a trip wire. Someone put the wire there. Could they have even known the doctor would be their victim?

Other incidents occur. A barn is burned. A child is found murdered. Someone did each of these things. The same person could not easily have done all of them. There is information about where various people were at various times. It’s like an invitation to play Sherlock Holmes and deduce the criminal. But in “The White Ribbon,” there are no barking hounds. The clues don’t match. Who is to even say something is a clue? It might simply be a fact seen in the light of suspicion.

Life continues in an orderly fashion, as a gyroscope tilts and then rights itself. The baron steadies his people. The doctor resumes his practice, but is unaccountably cruel toward his mistress. The teacher teaches, and the students study, and they sing in the choir. Church services are attended. The white ribbon is worn by children who have been bad but will now try to be good. The crops are harvested. The teacher courts the comely village girl Eva (Leonie Benesch). And suspicion spreads.

I wonder if it’s mostly a Western feeling that misfortune is intolerable and, to every degree possible, death must be prevented. I don’t hear of such feelings from Asia or Africa. There is more resignation when terrible things happen. Yes, a man must not harm another. He should be punished. But after he causes harm, they don’t think it’s possible to prevent any other man from ever doing the same thing.

In this German town, there is a need to solve the puzzle. Random wicked acts create disorder and erode the people’s faith that life makes sense. The suspicion that the known facts cannot be made to add up is as disturbing as if the earth gave way beneath our feet.

Haneke has a way of making the puzzle more interesting than its solution. If you saw “Cache,” you’ll remember how, after a certain point, a simple shot by an unmoving camera became disturbing even when nothing happened. It wasn’t about what we were seeing. It was about the fact that someone was looking, and we didn’t know why.

It’s too simple to say the film is about the origins of Nazism. If that were so, we would all be Nazis. It is possible to say that when the prevention of evil becomes more important than the preservation of freedom, authoritarianism grows. If we are to prevent evil, someone must be in charge. The job naturally goes to those concerned with enforcing order. Therefore, all disorder is evil and must be prevented, and that’s how the interests of the state become more important than the interests of the people.

I wonder if Haneke’s point is that we grow so disturbed by danger that we will surrender freedom — even demand to. Do we feel more secure in an orderly state? Many do. Then a tipping point arrives, and the Berlin Wall falls, or we see the Green Revolution in Iran. The problem, as philosophers have noted, is that revolutionaries grow obsessed with enforcing their revolution, and the whole process begins again.

Haneke’s genius is to embed these possibilities in films rooted in the daily lives of ordinary people. He denies us the simple solutions of most films, in which everything is settled by the violent victory of one side. His films are like parables, teaching that bad things sometimes happen simply because they . . . happen. The universe laughs at man’s laws and does what it will.

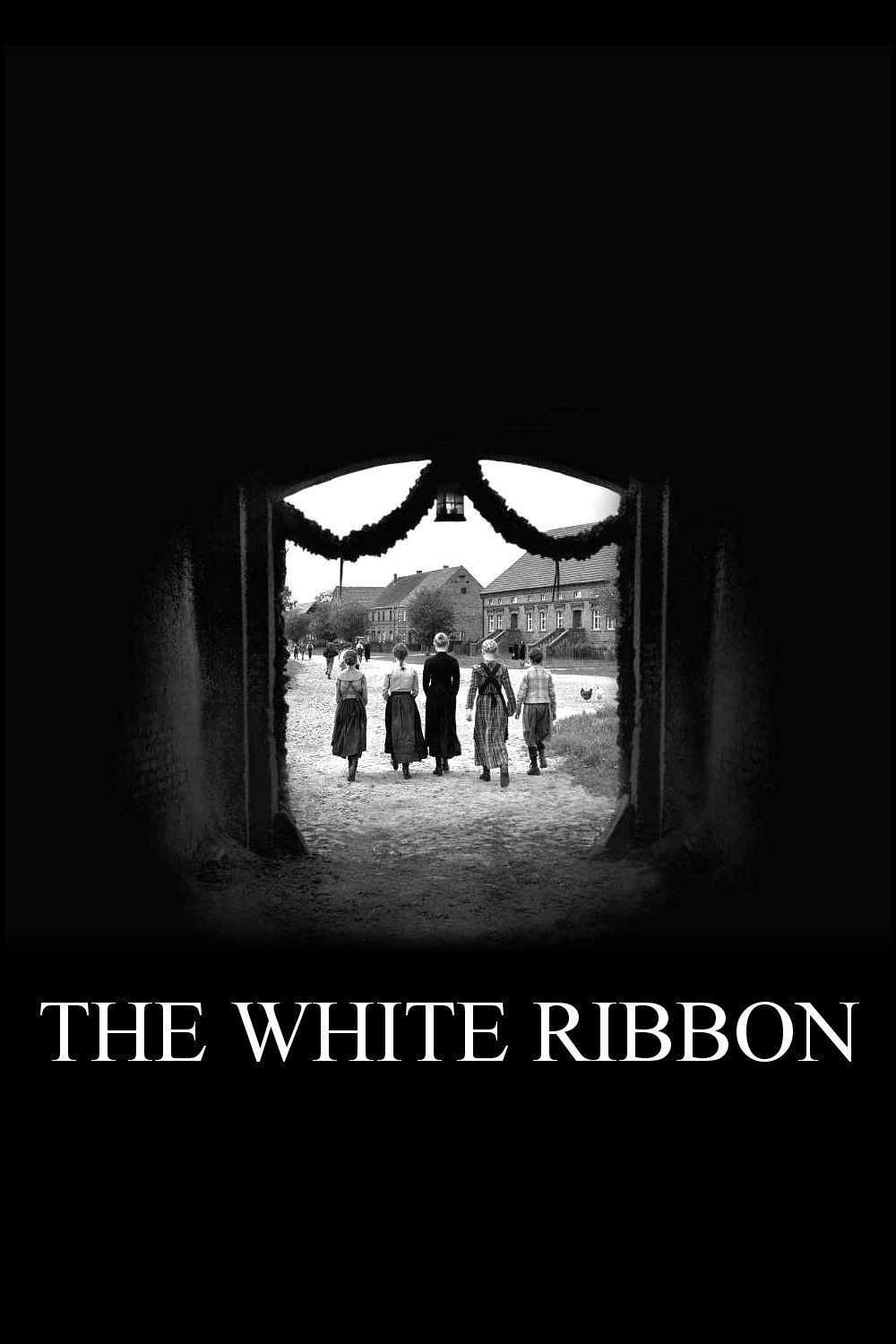

The film is visually masterful. It’s in black and white, of course. Color would be fatal to its power. Perhaps because black-and-white film stock is hard to find, Haneke filmed in color and drained it away. If a color version is ever released, you’ll see why it’s wrong. Just as it is, “The White Ribbon” tells a simple story in a village about little people and suggests that we must find a balance between fear and security.