“The Warrior” tells the story of a fierce warrior who changes the direction of his life after a mystical visionary moment. Lafcadia (Irfan Khan) is an enforcer in the employ of a cruel lord in the far northwest Indian state of Rajasthan. When a village cannot pay its taxes because of a bad harvest, the lord has their leader beheaded, and orders the warrior: “Teach them a lesson.”

Lafcadia and his men ride out to the village and rape, pillage and burn — and then the warrior sees a young village girl wearing an amulet given to her earlier that day by Lafcadia’s son; he understands that in killing any child he might as well be killing his own. He has an inexplicable image of a snowy mountain vista, and he vows: “I’ll never lift a sword again.” The lord is enraged: “No one leaves my service. Bring me his head by dawn.”

And so now the hunter has become the hunted. And the man who is hunting him, an ambitious warrior who was eager to replace him, faces a death sentence of his own if he does not return with the warrior’s head, or one that looks almost like it. This description makes “The Warrior” sound violent, I know, but almost all the violence takes place offscreen, and the action is located primarily in the warrior’s mind.

To save his life, and also because he is compelled to seek out the source of his snowy vision, he begins a long trek to the mountains of the north. He is accompanied by a orphaned thief (Noor Mani) whose family he may in fact have killed, and by a blind woman (Damayanti Marfatia) who is on a pilgrimage to a holy lake. “There’s blood written on your face,” she tells the warrior, and he tells the thief, “She’s right about me.”

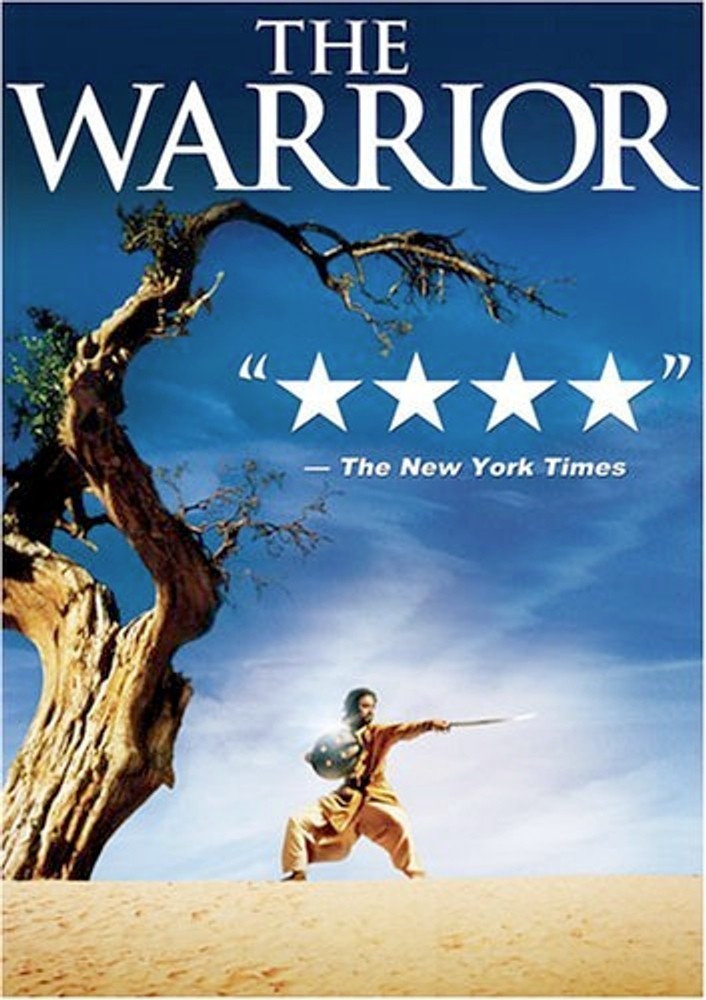

The movie, which is opening in America without fanfare some four years after Miramax bought the U.S. rights to it, arrives from Britain trailing clouds of glory: It won the Alexander Korda Award for Best British Film at the BAFTA Awards, and was named Best British Independent Film at the British Independent Film Awards. Filmed on location near the Himalayas, it was written and directed by Asif Kapadia, a documentary maker for the BBC.

The film is interesting for what it does not show. Not only is violence offscreen, but so is a lot of motivation; it is only by following the action and then thinking back through the story that we can understand the warrior’s thought process. And it is only because he eventually finds the source of his snowy vision that we understand the role it played early in the film. These are not flaws, just curiosities.

What is best in the film is its depiction of the warrior’s epic journey, photographed with breathtaking beauty and simplicity by Roman Osin, who just finished filming the new British version of “Pride and Prejudice.” The lands through which the warrior travels are familiar to my imagination from novels like The Far Pavilions, and by not setting the film in a particular period, the story takes on a timelessness. It is about people stuck in an ancient culture of repression, greed and revenge, and how some are able to escape it by a spiritual path. Parallels with the current eye-for-an-eye diplomacy of the Middle East are inescapable.

It may be that some American moviegoers will find the film’s form unsatisfactory. We are accustomed to closure and completion. If a threat is established at the opening of a film, by the end, we expect it to be enforced or evaded. We do not expect it to be … outgrown. Our plots are circular; “The Warrior” is linear. There is a kind of strange freedom in the knowledge that a story has cut loose from its origins and is wandering through unknown lands.

Note: It is hilarious that this elegant and thoughtful film has an R rating “for some violence,” while buildings are destroyed 9/11 style, thousands are killed and a nuclear cloud poisons a city in the PG-13-rated “Stealth.”