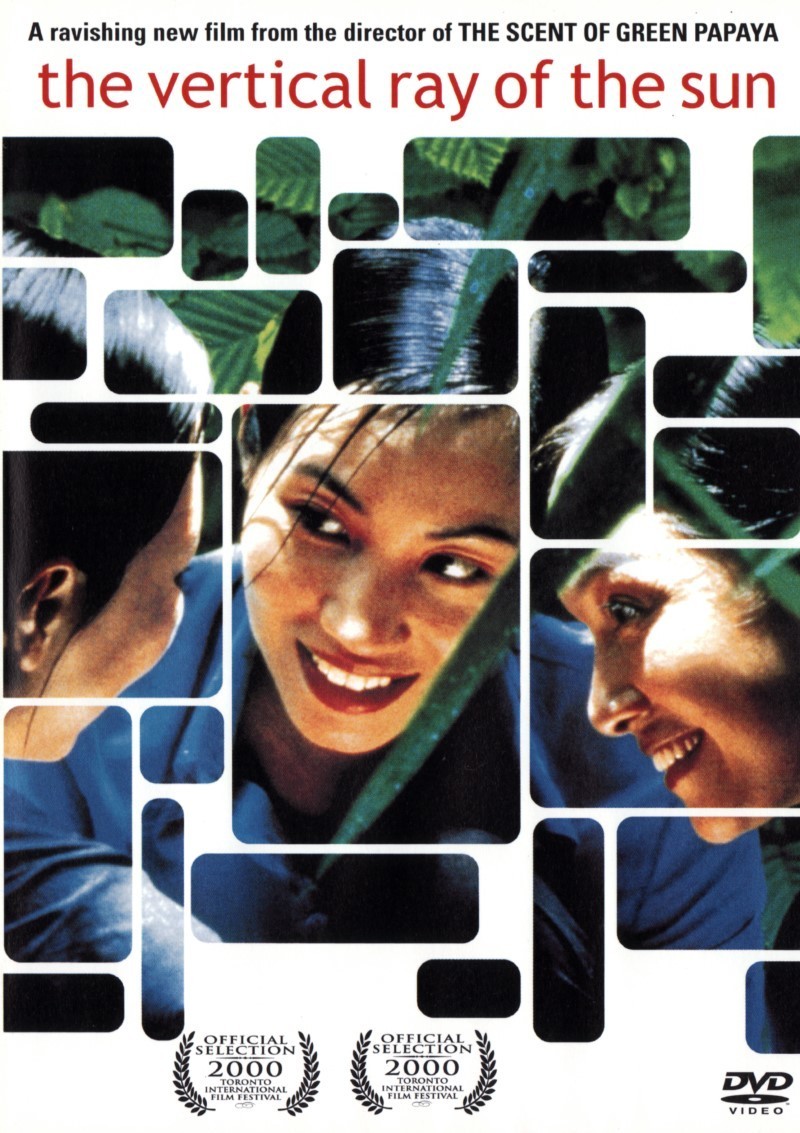

‘The Vertical Ray of Sun” is beautiful, languorous, passive–it plays like background music for itself. Filmed in a Hanoi that looks more like an Asian love hotel than a city, it’s a lush, sensuous work–the film equivalent of those old Mantovani albums with names like ”Music for Lovers Only.” It tells the stories of three sisters, two married, one single, and although it contains adulteries in the present, rumors of adultery in the past, one or perhaps two pregnancies and a hint of incestuous feelings, it would be fair to say that hardly anything happens.

Let me describe one shot. In the left foreground, a woman reclines on a bed. In the right background, a man looks out the window. It is raining. He is smoking. She lights a cigarette. For a time nothing happens except for the pleasure they take in silent companionship and smoking together. This time, passing in this intimacy without words, is a moment that says so much about their comfort in each other’s company that we realize most movies are about people who are doing instead of being . Little surprise that the director, Tran Anh Hung, grew up in Paris to love the work of Robert Bresson, that French master of films that were about the essence, not the adventures, of his characters. Tran was born in Vietnam, moved to France with his family at the age of 6, and made the remarkable debut film “The Scent Of Green Papaya” in 1993, when he was still in his 20s. It was the love story of a simple servant girl and a sophisticated rich boy, and it was set in French-ruled Saigon–a Saigon created for the film, astonishingly, entirely on a Parisian sound stage. Then came a trip to Vietnam to film ”Cyclo,” a rougher, more realistic story about street life in what had become Ho Chi Minh City. Now here is ”The Vertical Ray of the Sun,” filmed in Hanoi, but a Hanoi no more realistic than the Paris in MGM musicals like “An American in Paris.” ”I wanted my film to feel like a caress,” Tran told Trevor Johnston of the London Independent. ”It had to have a gentle smile floating through it, a sort of floating feeling.” He wanted to find a style, he said, ”which didn’t present the drama as a series of emotional problems for the various couples.” He has been so successful that his film may be maddening for those who expect conflict in their movies. The various couples do, in fact, have emotional problems, but they live in a sea of such emotional contentment that unhappiness is a wave that crests briefly and falls back, forgotten.

We meet three sisters. Lien, the youngest, is played by Tran Nu Yen-Khe, who is Tran’s wife and was the star of ”Green Papaya.” She still lives at home with her twin brother, Hai (Ngo Quang Hai). At times they chase each other around the house like children. At other times he awakens to find her in his bed because she ”got lonely” in the night. ”People think we are courting,” she says with delight as they walk in the street. They talk about what he would do if she ever got married. This is emotional, not physical incest.

Their older sister Khanh (Le Khanh) is married to a novelist who says he is stuck on the ending of a novel which may not even have a beginning. She has, for me, the most luminous moment in the movie, in a close two-shot where she is filled with something she wants to say, and then says it: She is pregnant. Do you know how a woman’s lips look when she delays with delight, holding back happy news? The pause before she speaks is a moment of such beauty. The third sister is Suong (Nguyen Nhu Quynh), whose husband is obsessed with his photographs of rare plant species.

Sometimes, she says, she thinks he cares more about his plants than about her. Actually, he also cares about another woman he lives with secretly on the island where he collects his specimens; they have a child. The nature of his life explains his long absences to both women, but Suong has a breathtaking scene where she tells him what she knows, how she knows it, and what she expects him to do about it.

The title, which can also be translated as ”At the Height of Summer,” captures a season of heat and humidity when motion is to be avoided and the most luxurious time of the day is waking while it is still cool. The sisters meet to prepare meals, gossip, confess and speculate. The men are more vaguely drawn. The film finds it so unnecessary to conclude and solve the character’s problems that after it’s over you may not be able to remember if it did. It is not about incident, but about nostalgia for the slowness and peace of days past.

Here is Tran again, in the London interview: ”My thoughts turned back to my childhood in DaNang, remembering the time when I’d be waiting to fall asleep at night, my mind racing from one thing to another, nothing precise. The smell of fruit coming in through the window, a woman’s voice singing on the radio. Everything was so vague. It was like a feeling of suspension. If I’ve ever experienced harmony in my life it was then. It was just a matter of translating that rhythm and that musicality into the new film.” Reading those words, I was reminded of a little-known but evocative film by Robert Altman named “Thieves Like Us” (1974) in which, in a small frame house in the summertime, on Sunday afternoon perhaps, the characters sit dozing in easy chairs and from a distant room comes the sound of a song on the radio. On such warm and idle afternoons there is the possibility that love-making lies ahead, or perhaps it lies behind; it is too much to think about just now.