Not all he was saying was “Give peace a chance.” When John Lennon and friends sang that song, and millions of anti-war protesters took up the chant, they were also saying “power to the people” (the name of another Lennon tune). And that, strangely, worried some of the nation’s top crooks: J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI, and various officials in the Nixon White House.

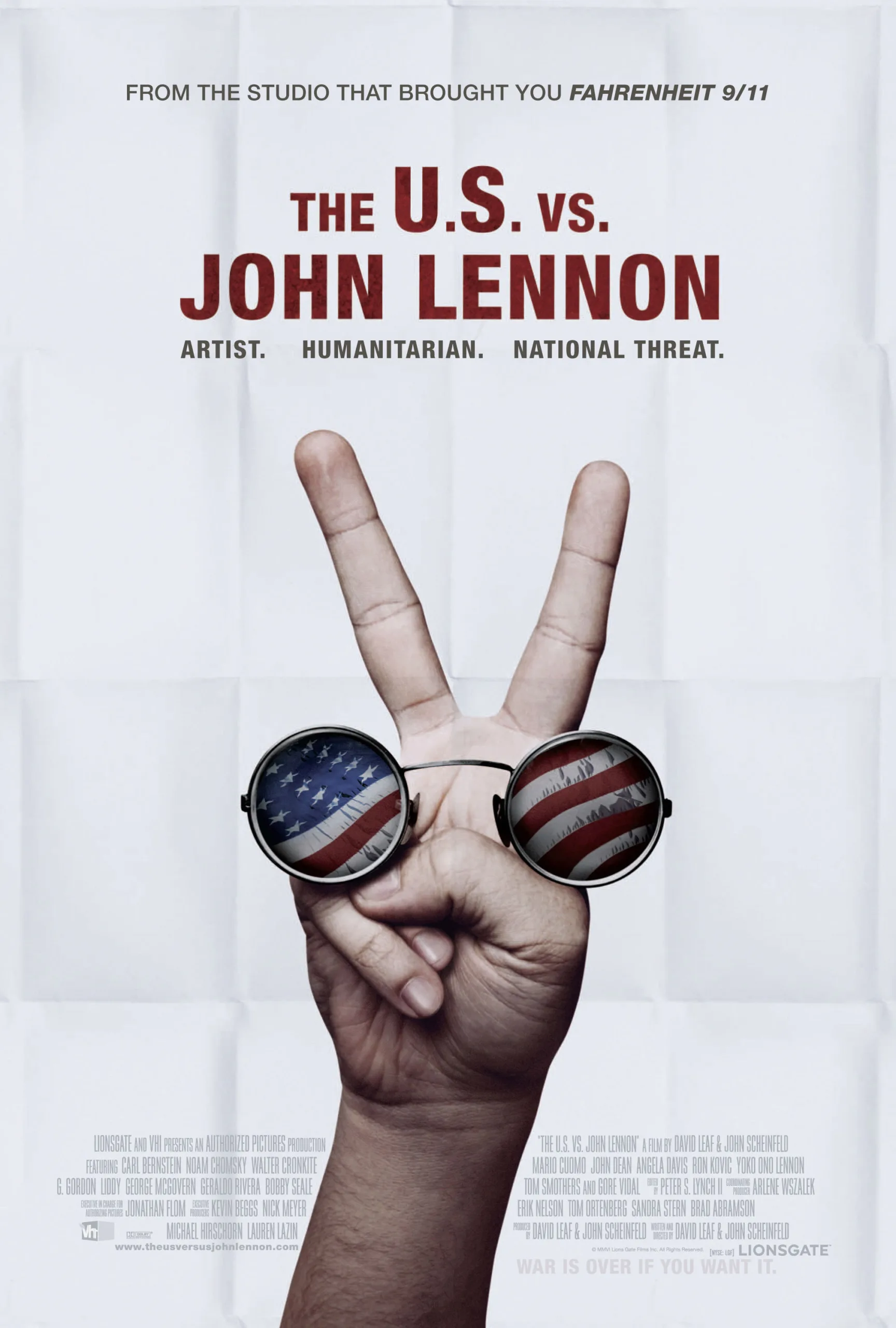

Make no mistake, Beatlemania was big, and we’ll probably never see anything like it again. But the idea, as writer and political activist Tariq Ali says in the documentary “The U.S. vs. John Lennon,” that an artist — even a former Fab Four mop-top — could pose any kind of threat to the interests of the most powerful nation on earth, is patently ridiculous. Nevertheless, Lennon was put under surveillance by the FBI and — with a gentle nudge in the form of a letter to the White House from Republican Sen. Strom Thurmond — attempts were made to deport him, for purely political reasons, as an “undesirable alien.”

“I’m just one of those faces, you know,” Lennon said. “People never like me face.”

When Nixon was re-elected by a landslide in 1972, Lennon was suddenly no longer a threat and the White House lost interest in him. The bureaucracy of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, however, kept churning away, and Lennon did not achieve legal victory, or his green card, until 1976. (He would live another four years.) Unclassified memos, from the FBI’s Hoover to White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman, showed improper political interference in an immigration proceeding. Imagine.

“The U.S. vs. John Lennon,” written and directed David Leaf and John Scheinfeld, is remarkable mainly for being so tepid, given its charismatic protagonist and its setting during one of the most turbulent periods in modern American history. Even at 99 minutes, it feels padded, repetitious and unfocused, with too much time spent establishing Lennon’s “rebel” bona fides and not nearly examining the preposterous (and ultimately failed) immigration case against him that stretched over 4½ years.

Also, probably because Yoko Ono’s cooperation was essential to getting the film made, it unfairly whitewashes Lennon, strips him of much of his complexity, and eliminates any mention of his traumatic separation from Ono in 1973 and 1974, when he lived in Los Angeles.

Still, it’s great to see a lot of this footage of Lennon — playful, engaged, warm and spontaneous — whether he and Yoko are being interviewed inside a large white bag (a hilarious scene), in a bed at the Amsterdam Hilton, or on the Mike Douglas or Dick Cavett shows. Lennon speaks of his legal dilemma as “Kafkaesque,” but he also wryly appreciates the absurd humor of the situation. As his case drags on through seemingly endless appeals, he remarks that it’s keeping the conservatives happy because at least it looks like they’re doing something, and it’s keeping the liberals happy because he hasn’t actually been deported yet. So … everybody’s happy.

John and Yoko even came up with their own extra-legal attempt to fight the INS, by declaring themselves citizens of a new country, Newtopia, requesting recognition from the United Nations, and asking the U.S. for diplomatic immunity. Now that is a brilliant strategy. Of course, like most of Lennon’s symbolic idealistic gestures, be they utopian or Newtopian, it didn’t quite work. But that wasn’t really the point, was it? For Lennon, the idea was always to show people that change was only possible once you believed it was possible.

“So, flower power didn’t work. So what?” he tells a crowd at the concert for John Sinclair, who had served 2½ years (and was sentenced to 10) for giving two marijuana joints to an undercover policewoman. (This particular utopian gesture did work — the Michigan Supreme Court ordered Sinclair released from prison a few days later.)

Lennon was always ready to grab the next wave. His and Yoko’s publicity stunts for “peace” were condescendingly dismissed as silly, naive and even trivializing, but Lennon was dead serious about promoting the idea of peace: “We’re selling it like soap, you know?” And in 1969, there was indeed something liberating and comforting in seeing those billboards (and, in 1971, hearing that song): “WAR IS OVER! (If you want it.) Happy Christmas from John and Yoko.”

“The U.S. vs. John Lennon” touches on all of this, and a dose of idealism may be helpful at this deeply cynical moment in American history. (One can’t help wondering what a 66-year-old Lennon would have made of Geraldo Rivera, interviewed here, as a Fox News correspondent.) When journalist Carl Bernstein speaks of politically motivated surveillance campaigns and refers to the Nixon administration as “a rogue presidency, a criminal presidency,” you know the parallels the filmmakers intend you to draw.

Gore Vidal puts it bluntly. Lennon sang about love and peace and “represented life, and that is admirable,” he says. “And Mr. Nixon, and Mr. Bush, represent death. And that is a bad thing.”