“The United States vs. Billie Holiday” is so misguided that it’s hard to know where to start griping about it. It wallows in cruelty, misery, and degradation without providing insight into the historical personages who are so thoughtfully depicted by its cast. In the title role, singer Andra Day inhabits Holiday with such intensity that she partially redeems the movie. But there’s a major caveat: you’ll likely spend the whole running time wishing Day had been given a vehicle with more to say about Holiday than this one, the gist of which can be summed up as, “That poor junkie sure could sing.”

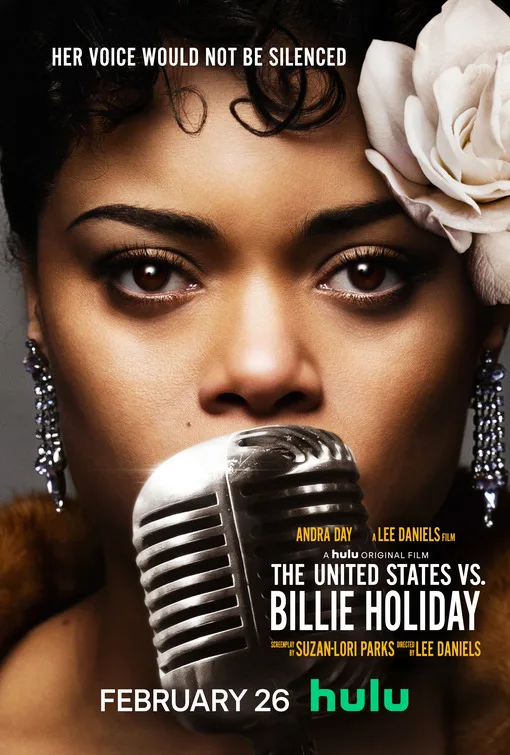

Directed by Lee Daniels and written by Suzan Lori-Parks, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday” is a film about a brilliant artist and drug addict that seems less interested in the art than in the pornographically exact details of the addiction (and the self-damage that often comes with it, such as alcoholism, self-destructive/abusive relationships, and sexually compulsive behavior). If you called the movie up on Hulu, its debut streaming platform, hoping to watch facsimiles of Holiday and her bandmates, lovers, and hangers-on tying off and shooting up, often with closeups of needles going into arms (and in one case, blood spurting from an injection hole), you won’t be disappointed. This is also your movie if you want to watch men beating each other up over women, men beating women up over men, Black people selling out and exploiting other Black people for clout or money, and an array of cardboard cutout white authority figures tormenting the Black characters.

The poker-faced Caucasoid sadists in the film (led by Garrett Hedlund’s Harry J. Anslinger, the first chief of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Bureau of Narcotics, an outspoken racist who believed jazz was jungle music and a corrupting influence on whites) don’t so much incarnate the ugliness of white supremacy in mid-20th century America as give viewers heels that they can boo. Anslinger even makes a point of showing up in person at key points in the narrative of torment that he has authored for Holiday, as punishment for daring to continue singing her anti-lynching ballad “Strange Fruit” after being warned not to. Holiday lost her cabaret license in a drug bust, and was targeted again in a subsequent bust that biographers agree was based on planted narcotics.

This film’s version of Anslinger might as well be Elmer Fudd chasing a wascally wabbit. The cartoonish depiction of Anslinger (drawn from the film’s source material, Johann Hari’s Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs) is reminiscent of the otherwise excellent historical drama “The Hurricane,” which made it seem as if Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a champion boxer railroaded on a phony murder charge, was victimized not by appendages of an American government that had been around for centuries, but by a lone, bad white cop who hated him for being Black.

This is, of course, a familiar and regrettable tendency in Hollywood biopics dealing with race and inequity—a dramatic shortcut. It’s easy to make viewers despise the sort of melodramatic movie villain who would twirl a mustache if he had one, and hard to make them care about systemic and institutionalized racism, or the unequal enforcement of drug laws that disproportionately hurt entertainers of color, and still do. (The drug habits of white stars like Judy Garland were treated more sympathetically by law enforcement.)

Even more unfortunate is the decision to divide screen time between Holiday and a Black junior FBI agent named Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes), who is based on a real man who regretted his role in Holiday’s persecution but didn’t have the kind of longstanding love affair with Holiday depicted in this movie. A condensed excerpt from Hari’s book says Fletcher set up one of Holiday’s busts (though apparently not one that sent her to prison, as depicted in Daniels’ movie). He was seen dancing with her at a club a while later, and many years after that was sent a signed copy of Holiday’s autobiography with a note from the singer that read, in part, “Most federal agents are nice people. They’ve got a dirty job to do and they have to do it. Some of the nicer ones have feelings enough to hate themselves sometime for what they have to do.” But Daniels and Parks go several extra miles beyond that, showing Fletcher not just falling in love with the singer but tanking testimony to make amends for that early bust, then becoming a constant, nurturing presence in her life, up to and including her dying days in a hospital following her final overdose (along the way, Fletcher also becomes a junkie, like nearly everyone else in Holiday’s orbit).

What’s questionable here isn’t the lack of veracity (if infidelity to history were a deal-breaker for audiences, Shakespeare wouldn’t have lasted five minutes) but the message it conveys. What we come away with here is the story of a race traitor who expresses his guilt about setting up one of the century’s greatest singers by entering into a redemptive affair with her, and becoming so adored and trusted that he learns her bleakest secrets. Two of these—witnessing acts of racist violence and getting turned out by her own mother in the brothel where she was raised—are dramatized in a tour-de-force, single-take, Grand Guignol tracking shot that turns Holiday’s trauma into a theme park ride. It’s as if the Haunted Mansion at Disney World had been replaced with a tour of Richard Pryor’s childhood.

And what, the reader may rightly ask, does any of this have to do with “Strange Fruit”? It’s hard to say. The film is so poorly structured and ineptly edited that I often wasn’t sure what I was looking at, when it was taking place, or what the filmmakers wanted me to take away, other than that Holiday had a wretched early life; that her adulthood was an equally miserable slog, filled with self-medicating that made things worse; and that despite it all, she was a crackerjack song interpreter who left some classic recordings behind. Natasha Lyonne shows up as Tallulah Bankhead, Holiday’s maybe-lover, and disappears instantly. Years bleed into other years. Much dope is shot.

Holiday’s indefatigable spirit gets buried under misery porn that’s a bit much even by Daniels’ standards. At least “Precious” was audacious. You could tell Daniels was going for a semi-satirical, Todd Solondz-like vibe, where you were supposed to ask, “Is this meant to be funny, and am I a bad person for laughing?” There’s no such tonal cheekiness here. The film is solemn as can be, hammering nails into Billie Holiday’s ankles and wrists and raising her up on the cross at the end. Daniels frames Holiday in a tight closeup and watches her sing as she stares into the middle distance through glazed eyes. He crosscuts between Holiday singing onstage and getting shtupped backstage by a smooth criminal. He stares at her defeated, puffy face as she lies in a hospital bed with a catheter snaking from her hospital gown, talking to her pals about how her liver has failed. There seems to be no dramatic objective to scenes like these other than to remind us yet again, “Billie Holiday was a junkie, drugs are bad.”

Over the course of two hours that feel like three, “All of Me” loops in and out of the soundtrack in varied arrangements, including a rumbling funereal version that may very well show up in a trailer advertising an R-rated, dark-and-gritty reboot of, hell, who knows which early 20th century cartoon property. Maybe Betty Boop. The film itself seems strung out, and not in an interesting way. It needed an intervention.

Now available on Hulu.