Hitchcock said that most of his films were really about the same thing, the Innocent Man Wrongly Accused.

These days audiences do not have the patience to follow a man as he fights against persecution; the films of our time are about the Innocent Man Wrongly Blown Away and Immediately Forgotten. When the theme does find new life, in something like “The Fugitive,” it is translated into action, and the hero spends the movie being clever about how he eludes capture, instead of wrestling with the world’s unfairness to him.

Too bad (although “The Fugitive” is a splendid film), because we all have deep wells of guilt within, and often in our dreams are framed of crimes we did not commit. In these nightmares we try to defend ourselves, try to explain, but the authorities ignore us. Such situations are so frightening and frustrating that I wonder how Hollywood ever got the idea that it was scarier to shoot people, or blow them up – which simply releases the tension.

Franz Kafka’s novel “The Trial” is one of the best stories ever written about the Innocent Man, and all the better because there is a sense that Josef K., its hero, secretly suspects that he must have done something wrong to deserve such cruel treatment from the authorities.

Josef is awakened one morning by his landlady, who reports there are men to see him. She reveals by her manner that she’s already found him guilty; anyone who draws unconventional visitors so early in the day is probably unreliable in many other ways. The police have come to inform Josef about the charges against him – charges that are never spelled out, although Josef spends the rest of the story trying to find out what he has allegedly done.

Do people read Kafka any longer? I am thinking of real readers, people who love the smell and feel and privacy of a book, not students working their way through an assignment. It is ironic that this new film of “The Trial” will probably play, for most of its viewers, as an entirely new experience. They will not have read the book, nor will most of them have seen Orson Welles’ great version, also called “The Trial” (1963).

Too bad, because this film, directed by David Jones and written by Harold Pinter, is lacking in the anger and fear which inhabited both the Kafka and Welles stories. Josef K., in the earlier versions, was outraged to his very core that he could be treated in such a way. True, he might secretly be guilty of something – who is not? – but if the state can’t put a name to it, then it should stay the hell out of his life.

Kafka wrote in the early years of the century. Welles was shaped by them. Today we have been tamed by the notion of a powerful state; most of us are frightened even to be pulled over by a traffic cop. Yet we believe, naively, that if we follow the rules everything will be set straight in the end. That seems to be Josef’s belief in this version of “The Trial;” he is played by Kyle MacLachlan as an upright, reserved, logical man who continues patiently to try to defend himself.

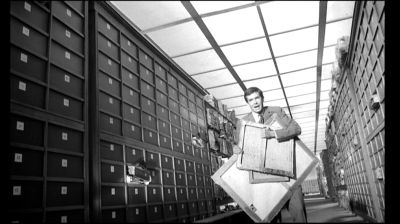

The star of Orson Welles’ film was Anthony Perkins. Much better. Perkins projected the kind of man who, told he is guilty, would look in the mirror and see that they were probably right. He was jumpy, nervous, filled with squirms and ticks. Welles put him in one of the most extraordinary landscapes in movie history: A city of vast blasted empty spaces and towering lifeless apartment buildings that looked like cell blocks. When he went to visit an archive, it looked filled with the dusty records of all recorded time. When he went to appeal to a famous lawyer (played by Welles), the advocate’s flat was lit by candles, and not half a dozen candles, but hundreds or thousands, blazing away on every horizontal space.

In the Welles film there always seemed to be someone in the next room, snickering, and then disappearing from view just a second before Josef could get a good look. The whole feel of the film was paranoid. This new “Trial” seems more clean and well-lit. It still provides opportunities for great walk-on performances (Anthony Hopkins has a brief scene as a priest who tries to make it easier for Josef toward the end, and steals, not just the scene, but almost the last half of the movie). It is a solid, respectable screen adaptation, but it lacks the madness.

A movie need not be “faithful” to a book (adaptations are not marriages and remakes are not adultery). But if it is based on a book at all, the filmmakers must have seen something worth preserving. In the case of Kafka’s masterpiece, it is the uneasy feeling that if the state ever gets its lunch hooks into us, we’re guilty until proven innocent. This queasiness is as appropriate today as in Kafka’s lifetime; the trials of Josef K. foreshadow the fate of anyone unlucky enough to attract the attention of the IRS, or Rush Limbaugh.

Assignment: Buy a paperback of The Trial and read it. It is written in a tightly controlled, flat, factual tone that is echoed (without the intensity) in the narration of those true-crime TV infotainments. Then rent the Welles film. Then see the Jones version of “The Trial,” in a theater or eventually on home video. Meditate on the differences among the three versions, and you will discover insights into the difference between artistry and craftsmanship, between inspired madness and mere indignation.