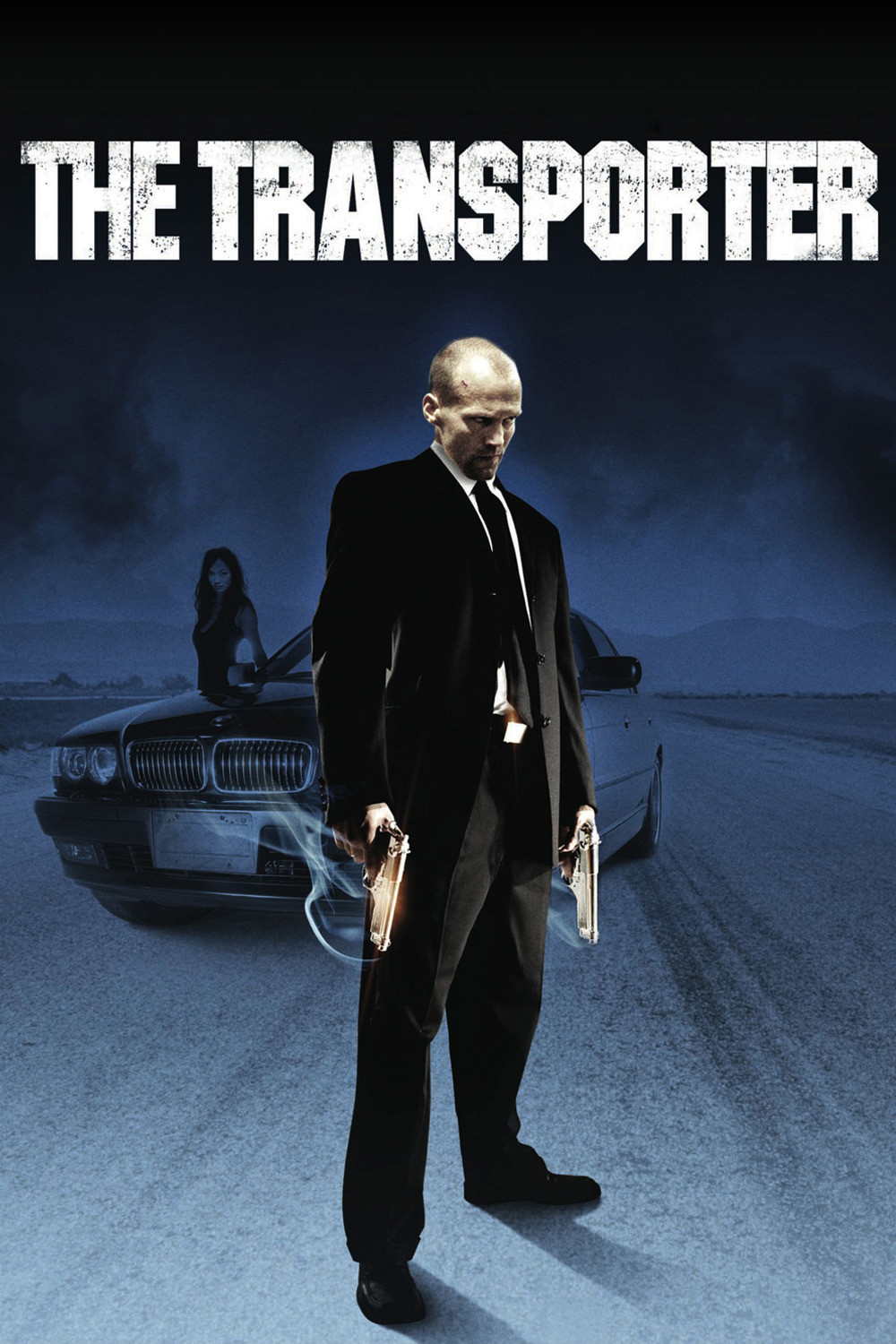

The marriage of James Bond and Hong Kong continues in “The Transporter,” a movie that combines Bond’s luxurious European locations and love of deadly toys with all the tricks of martial arts movies. The movie stars Jason Statham (who has pumped a lot of iron since “Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels“) as Frank Martin, a k a the Transporter, who will transport anything at a price. His three unbreakable rules: never change the deal, no names, and never look in the package.

Unlike Bond, Martin is amoral and works only for the money. We gather he lost any shreds of patriotism while serving in the British Special Forces, and now hires out his skills to support a lifestyle that includes an oceanside villa on the French Riviera that would retail at $30 million, minimum.

In an opening sequence that promises more than the movie is able to deliver, Martin pilots his BMW for the getaway of a gang of bank robbers. Four of them pile into the car. The deal said there would be three. “The deal never changes,” Martin says, as alarms ring and police sirens grow nearer. The robbers scream for him to drive away. He shoots the fourth man. Now the deal can proceed.

And it does, in a chase sequence that is sensationally good, but then aren’t all movie chase scenes sensationally good these days? There have been so many virtuoso chase sequences lately that we grow jaded, but this one, with the car bouncing down steps, squeezing through narrow lanes and speeding backward on expressways, is up there with recent French chases like “Ronin” and “The Bourne Identity.” The movie combines the skills and trademarks of its director, Corey Yuen, and its writer-producer, Luc Besson. The Hong Kong-based specialist in martial arts movies has 43 titles to his credit, many of them starring Jet Li and Qi Shu. This is his English-language debut. Besson, now one of the world’s top action producers (he has announced nine films for 2003 and also has “Wasabi” in current release), likes partnerships between action heroes and younger, apparently more vulnerable women. Those elements were central in his direction of “La Femme Nikita,” “The Professional” and “The Fifth Element.” Now he provides Frank Martin with a young woman through the violation of Rule No. 3: Martin looks in the bag.

He has been given a large duffel bag to transport. It squirms. It contains a beautiful young Chinese woman named Lai (Qi Shu, who at age 26 has appeared in 41 movies, mostly erotic or martial arts). He cuts a little hole in the bag so she can sip an orange juice, and before he remembers to consult his rules again he has brought her home to his villa and is embroiled in a plot involving gangsters from Nice and human slave cargoes from China.

The movie is by this point, alas, on autopilot. Statham’s character, who had a grim fascination when he was enforcing the rules, turns into just another action hero when he starts breaking them. I actually thought, during the opening scenes, that “The Transporter” was going to rise above the genre, was going to be a study of violent psychology, like “La Femme Nikita.” No luck.

Too much action brings the movie to a dead standstill. Why don’t directors understand that? Why don’t they know that wall-to-wall action makes a movie less interesting–less like drama, more like a repetitive video game? Stunt action sequences are difficult, but apparently not as difficult as good dialogue. Unless you’re an early teens special effects zombie, movies get more interesting when the characters are given humanity and dimension.

Frank Martin is an intriguing man in the opening scenes, and we think maybe we’ll learn something about his harsh code and lonely profession. But no: We get car leaps from bridges onto auto transporters. Parachute drops onto the tops of moving trucks. Grenades, rocket launchers, machine guns (at one point a friendly inspector asks Martin to explain 50,000 spent rounds of ammo). There is of course an underwater adventure, tribute to Besson’s early life as the child of scuba-diving instructors. At one point, Martin tells Lai, “It’s quiet. Too quiet.” It wasn’t nearly quiet enough.