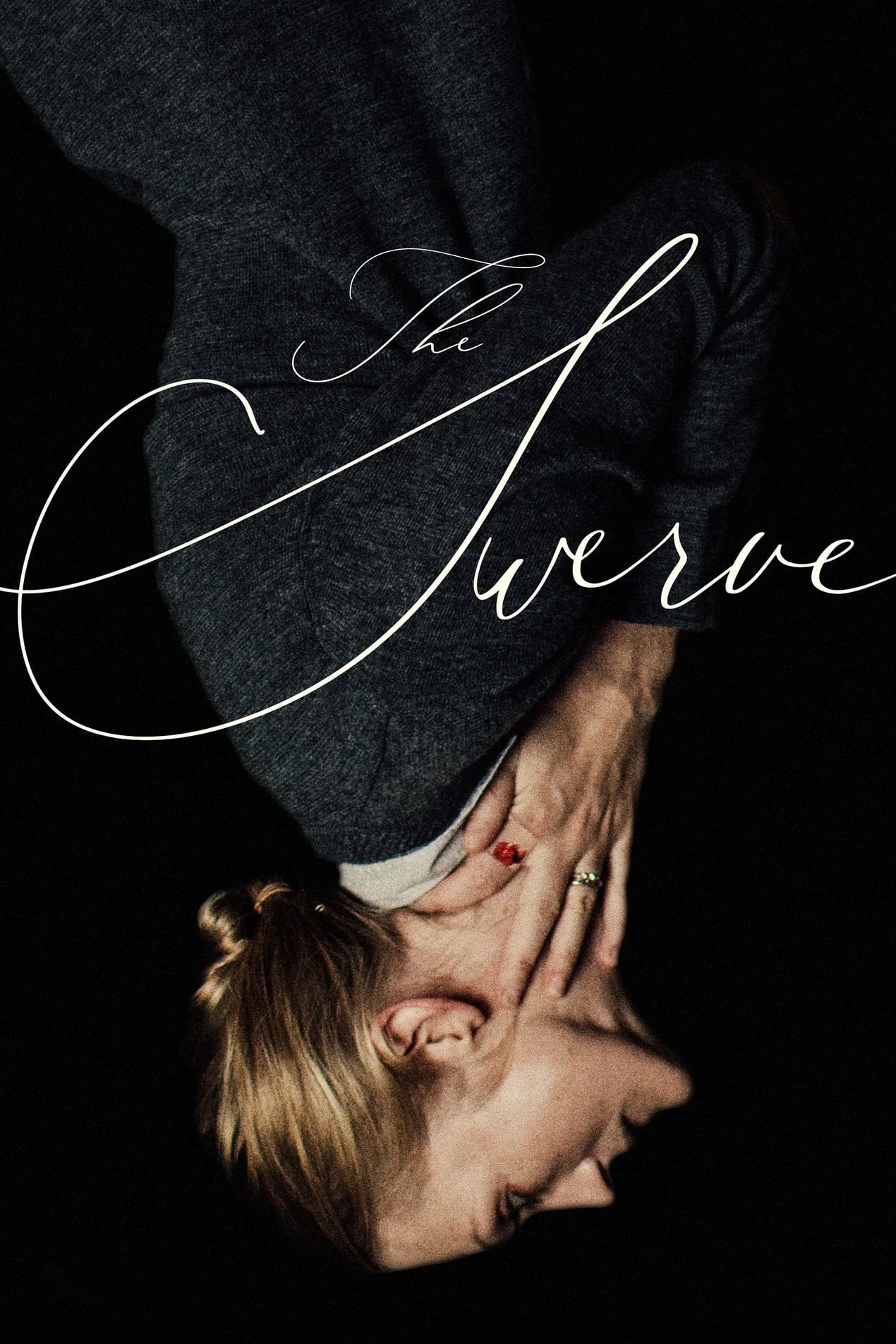

It’s hard to pinpoint the moment when Holly (Azura Skye) goes off the rails. What we witness over the course of “The Swerve,” a powerful debut from writer/director Dean Kapsalis, is the total breakdown of a human being, an accelerated dissolution of defenses, of sanity, until there is no turning back. Seen in this light, Holly’s breakdown isn’t due to any external circumstance whatsoever. It’s like there’s been a monster inside her whole life, waiting patiently for the chance to finally express itself to the fullest after years of severe repression. By the time we meet up with Holly at the beginning of “The Swerve” the situation is already well past the point of no return.

Holly has what appears to be a very normal regulated life. She teaches high school English. Her husband (Bryce Pinkham) manages a grocery store. They have two teenage sons who treat Holly like a maid/chauffeur. They don’t look up when she comes in the room, and when they speak to her it’s always with irritation, impatience and contempt. Holly, submissive and so thin she looks breakable (she’s called “anorexic” during a turbulent family dinner), doesn’t have it in her to say to her wretched rude sons, “Hey. Don’t talk to me like that.” All of these are fairly rote annoyances, but Holly’s response is not rote. It is obvious just from looking at her that she is struggling mighty with an interior typhoon—some gigantic disturbance which is very rapidly becoming unmanageable.

But what is wrong, exactly? Holly obsesses on a mouse she saw in the corner of her bedroom. The shadows underneath her huge tragic eyes show her insomnia, and the pills she takes barely makes a dent. She cuts her finger and picks nervously at the Band-aid in every scene. She develops a crush on one of her students (Zach Rand), which comes out in increasingly unstable and inappropriate ways. She is sure her husband is having an affair. He works late. “Inventory,” he reassures her. Everyone treats her like an invalid or an annoying moody teenager. Her mother bosses her around. Her sister Claudia (Ashley Bell) has led a peripatetic life filled with stints in rehab. A seething current surges underneath their interactions. Claudia does not forgive Holly for some transgression in the past, but Holly has no idea what it is.

This is reminiscent of Gena Rowlands’ chilly, cerebral Marion in “Another Woman,” a film I flashed on while watching “The Swerve.” Marion is baffled when she learns that so many people in her life have hostile feelings towards her. Her sense of self collapses. There is something in Holly that refuses to look within. It’s way too dangerous, there’s nothing but forbidden emotions down there. When Holly’s feelings eventually do pour out, they are huge and ugly, toxins from a lifetime of build-up.

Kapsalis knows the story he wants to tell and he sticks to it in a controlled way. Nothing distracts. The color scheme is extremely specific, all chilly blues and greys, monochrome, lifeless. The colors are so controlled that when bright colors do show up—in the the vivid greens of the produce section in the store, in the red and white checkered cloth over Holly’s fresh-baked apple pies—they register like a warning bell. Something is not right. Holly is often placed off-center in the frame, huddled in the corner with space above her head, a visual manifestation of the yawning abyss around her. Mark Korven’s unnerving score gives Holly’s mental state the tenor of a horror film.

One of the worst parts of mental illness is that the experience often eludes description. (John Keats’ “wakeful anguish” comes close.) One of the best descriptions I’ve found is from David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest: “Everything you see gets ugly. Lurid is the word … I fear this feeling more than I fear anything, man. More than pain, or my mom dying, or environmental toxicity. Anything.” It is the “lurid” quality that is so impossible to describe to people who have never experienced it. To go personal for a moment, during one of my breakdowns (my preferred term), I looked up at a bright pink sunset sky, and had the distinct impression that the sky had ripped open, that some invisible layer had flipped down like a flap on a piece of paper, revealing a sea of blank pink nothingness beyond. I thought the world was ending, that I was perceiving a catastrophe no one else could see. To this day, I think of that pink sky and shiver. It was the beginning of something, of reality unhinging.

In the “lurid” realm, Roman Polanski’s “Repulsion” is another reference point for “The Swerve,” where Catherine Deneuve’s submissive character deteriorates rapidly when left alone in the apartment over a long weekend. Grasping arms emerge push through the walls, shadows come to life, the ceiling gets lower and lower, a rapist hides in the corner. The final shot of “The Swerve” echoes “Repulsion”‘s final shot. Kapsalis is well-versed in his “women going off the rails” movie history.

None of this would register, however, without Azura Skye’s tremendous performance, as unblinkingly honest as anything Rowlands has done, although with its own specific rhythms. Skye’s face looks literally crushed at times, like her cheekbones have shattered, like something inside has collapsed, structural integrity breached. The deterioration progresses, and Skye meticulously tracks it: by the end she is unrecognizable from who she was at the beginning. Skye brings to the breakdown a feeling of inevitability: all this has been in Holly for decades. Skye’s work is not ingratiating to an audience, and uncompromising in its devotion to raw reality. Her choices are huge, and it’s astonishing the depths she is capable of going to. There’s no bottom. When Holly eats a piece of apple pie, alone in her kitchen, her lips jerk back, baring her teeth which then clang on the fork. It’s ferocious, animal fangs, fury now out in the open. In such details great performances are made and this is a great performance.

It’s not a requirement that art provide comfort, although many critics and audience members reject a film for being “depressing.” Roger Ebert’s thoughts on the 2005 film “The Weather Man” are appropriate: “One of the trade papers calls it ‘one of the biggest downers to emerge from a major studio in recent memory—an overbearingly glum look at a Chicago celebrity combing through the emotional wreckage of his life.’ But surely that is a description of the movie, not a criticism of it. Must movies not be depressing? Must major studios not release them if they are?” Promoting a hopeful message is fine, but not all art has to operate that way. Films about mental illness are often well-meaning but come from an outsider perspective, as opposed to straight from the heart of the lurid abyss. Films like “Repulsion,” “Melancholia,” “The Babadook” … are willing to go the distance, to depict the experience without necessarily showing the light at the end of the tunnel. The ending of “The Babadook” is one of the most accurate portrayals of “living with mental illness” I’ve ever seen. “The Swerve” is the opposite of comforting.

What is “the swerve” of the title? You’ll have to see it to find out.

Not being able to describe the experience of mental illness has serious repercussions. If you can’t describe it, then people don’t understand what it is. Empathy can’t develop. (Witness the mockery of Britney Spears during her meltdown some years back. I’m not sure what people think a breakdown looks like. Adorable?) We can’t de-stigmatize mental illness if we don’t know what it looks like when things get really really bad. “The Swerve” is not afraid to say: “This. This is how bad it can get.”

Now available on digital platforms.