The Corsican-born filmmaker Paul Vecchiali is probably best known, if at all, in the States as the producer of “Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles,” the Chantal Akerman picture that raised international consciousness when it topped the once-every-ten-years Best Film Ever poll in Sight and Sound magazine. Vecchiali was also a writer and director, and on the evidence of his 1970 picture “The Strangler,” presented in a solid-looking restoration by the indie distributor Altered Innocence, he’s definitely what Andrew Sarris would call a “subject for future research.”

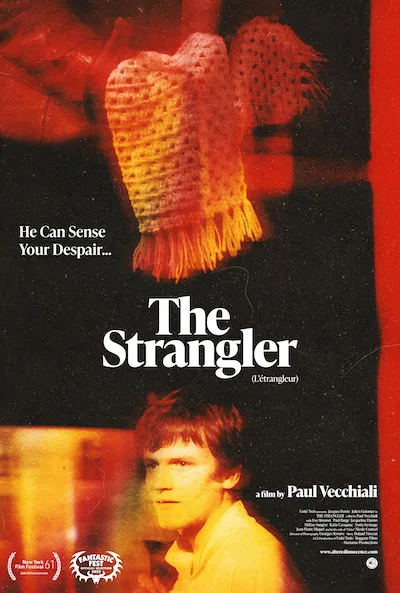

“The Strangler” is being touted as a “lost giallo,” and while its plot elements—a baby-faced young man habitually murders older women he considers “lonely”; a young woman drawn to the case volunteers to act as bait; a dogged detective resorts to unorthodox means to catch the killer—certainly suggest lurid genre fare, Vecchiali’s movie is not particularly interested in exploitation-cinema-style kicks. For one thing, the filmmaker mostly cuts away from the violence. The movie begins with a young boy, Émile, hammering apart his piggy bank and leaving his house, where he’d been pretending to be sick. Out on the town, he’s taken under the wing of a man in a pinstripe suit, and Émile watches as that man uses a white crocheted scarf to squeeze the life of a sorrowful older woman.

Decades later, Émile works at an outdoor market, selling vegetables and looking pleasant, albeit slightly creepy, as he observes which shoppers look as if they might be leading unfulfilled lives that he can snuff out. Jacques Perrin plays the psycho with an intriguing blandness. Émile is taken in by a police inspector masquerading as a criminal psychologist; he sees Dangret (stocky, gruff Julien Guiomar) seeking insight into the killer and finds a cat with whom he can play mouse. Émile begins sending Dangret kidnap-note-style missives expounding on motivations and announcing plans. The lonely younger woman, Eva Simonet’s Anna, eager to become a part of the case, becomes involved with Dangret. And she’s tracked down by the thief who’s started following Emile for unsavory reasons.

That’s quite a bit of plot, and pressing outside that material are enigmatic, out-of-focus shots speeding down a street. The movie’s disinclination to depict violence starts to fray, and Émile is tortured either by flashbacks or memories of other movies in which young gangs create havoc, including sexual assault. And there are some fascinating set pieces. The floating nightclub where one of Émile’s victims is a chanteuse, with its hammocks and nets and complement of sailor-shirted female dancers, is stunning. So, too, is a sociologically astute scene in which a gaggle of prostitutes nab the “hyena” who’s been tracking Émile and robbing the corpses of his victims and interrogate him in a café near the woods where they ply their trade. For all this, Vecchiali, who inserts some lines of disturbed poetry between the movie’s opening flashback and the contemporary diegesis, seems less concerned with story than the atmospheres of mortality and morbidity. Sometimes, he gets awfully close to what one would consider an apotheosis of the surreal. But not quite. Why?

Well, the cinema stylings here aren’t inordinately sophisticated or refined; most of the stalking-by-night scenes are quite flatly floodlit, which doesn’t do much to enhance an atmosphere of dread. The movie’s disregard for verisimilitude will sometimes grate even viewers who make a point of not thinking like Hitchcock’s least favorite audience member, the “Plausible”; for instance, the film starts with the killer having taken five lives, and yet the police force seems to have only two guys, Dangret and his boss, working on the case. For all that, the sensibility behind “The Strangler” is sufficiently unusual and stalwart. And maybe future Vecchiali revivals will flesh out the filmmaker well enough to land him in Sarris’ “Expressive Esoterica” category.

Now playing in select theaters.