In the Sweden of Ruben Östlund’s “The Square,” what was once Stockholm’s Royal Museum is now the “X-Royal” Museum, dedicated to contemporary art and its attendant values. The manner of the out-with-the-old, in-with-the-new change is conveyed in a scene in which workmen try to remove a statue of a horse and rider from the plaza in front of the museum; the statue, hoisted by the neck of its rider, breaks, decapitating the figure and ruining the plinth on which it once stood.

In the plinth’s place is installed the title square, or Square, a small space enclosed by a white light strip. Part of a larger exhibition concocted by an artist/sociologist, it’s meant to represent a communal “safe space,” so to speak. “The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring,” says the artist’s statement. “Within it, we all share equal rights and obligations.” The museum’s chief curator, Christian, is now hard-pressed to sell the message, and the exhibition, to the public.

But Christian, a handsome, clearly accomplished professional played by Claes Bang in a consistently committed performance that’s probably the best thing in this largely misbegotten movie, is distracted. He’s distracted by Modern Life, or Postmodern Life, or whatever you want to call it. In a scene depicting Christian’s commute to work, writer/director Östlund unveils his on-the-nose approach to social satire via sledgehammer. He opens with a shot of a homeless man lying on a clean Stockholm sidewalk. On the soundtrack, a voice keeps asking, “Would you like to save a life today?” The voice, we see in a wider shot, belongs to one of those on-the-street clipboard-holding solicitors for subscriptions to social services. Yes, once again it’s “WHAT INCREDIBLE IRONY” time—that guy is maybe dying just feet away, and here’s this person asking passersby, who are both indifferent to her and the homeless guy, if they are interested in saving a life! Whoa!

The street scene resolves with Christian discovering he’s been robbed of wallet, phone, and cufflinks. He can’t believe the last part. With the help of a computer-savvy subordinate named Michael (Christopher Læssø), Christian manages to track the phone, and he and Michael hatch an inane scheme to get it back by circulating a threatening letter in the housing project where the device has alit. This ploy actually works, but there are consequences, and while dealing with these consequences, Christian unthinkingly signs off on a marketing campaign concocted by a couple of cartoon Millennials. And this almost literally blows up in his face.

This is not a terribly plot-driven movie; indeed, at two hours and twenty minutes it’s rather a ramble. The movie has to accommodate other anecdotes commenting on Modern Life, including Christian’s one-night-stand with an American journalist (Elisabeth Moss) who inexplicably keeps a chimpanzee in her apartment and engages in a surprising game of tug-of-war with a condom post-coitus. There’s also an issue with one of the exhibitions, an installation of piles of gravel that the museum’s clean-up crew keeps inadvertently subtracting from after hours.

Östlund has a particular stylistic strategy for creating and ratcheting up tension in his scenes. He establishes the parameters of a given exchange and then deliberately withholds reverse shots. A character will ask a question, and one expects the other character to answer, and instead, Östlund holds the shot. The character waits. The answer comes, but there’s no cutaway. In the scene in which Christian and Michael go to the housing project with their letters, Michael nervously waits in the car, and he’s approached by people on the street who knock on the windows, ask him about the car, and vaguely menace him. The camera never leaves the car, keeping Michael in anxious medium-close-up the whole time. This method is effective except when it’s not; then it’s just irritating.

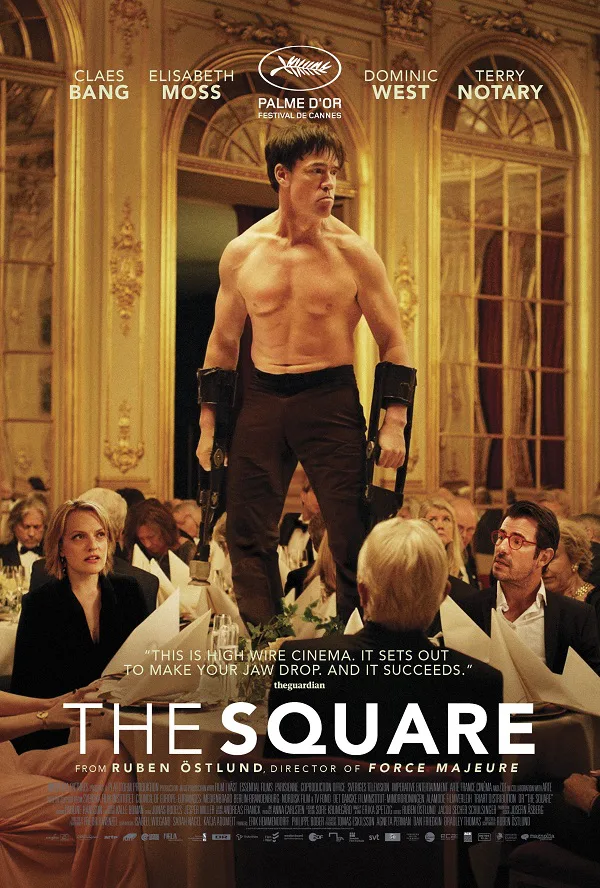

If you are asking why Christian did not just report the stolen phone to the police, well, that’s interesting: the Sweden of this movie seems to have no police, or security guards, or doormen. When a performance art stunt at a gala dinner—the movie’s signature set piece, I suppose—goes horribly wrong on account of the artist’s unstoppable aggression, it’s up to the dinner guests to put a stop to it. Which of course they take an unconscionably long time to do, because, you know, Modern Life. Similarly, an irritated recipient of Christian’s letter, seeking payback, gets into Christian’s apartment building no problem, and creates large hassles therein.

Okay, then, if that’s the society Östlund envisions, that’s his privilege. Except the movie doesn’t even obey its internal logic. The museum’s snooty overboss, Elna, played by Swedish musician Marina Schiptjenko, is depicted in one scene as appalled by the “viral” video advertising for The Square exhibition; she’s worried about funding, among other things. In almost the very next scene she sits placidly and appreciatively while some of her benefactors are assaulted in the name of art.

The conceptual-fish-in-a-barrel potshots at contemporary art alternate with an ostensible critique of masculinity and privilege, building to a climax that endorses a compassion that’s mealy-mouthed and insufficient. For all the skill and polish on display, “The Square” is never anything beyond facile and pleased with itself.

It says something unsettling about the times that the Palme d’Or was awarded this year at Cannes to a work so flat-out reactionary.