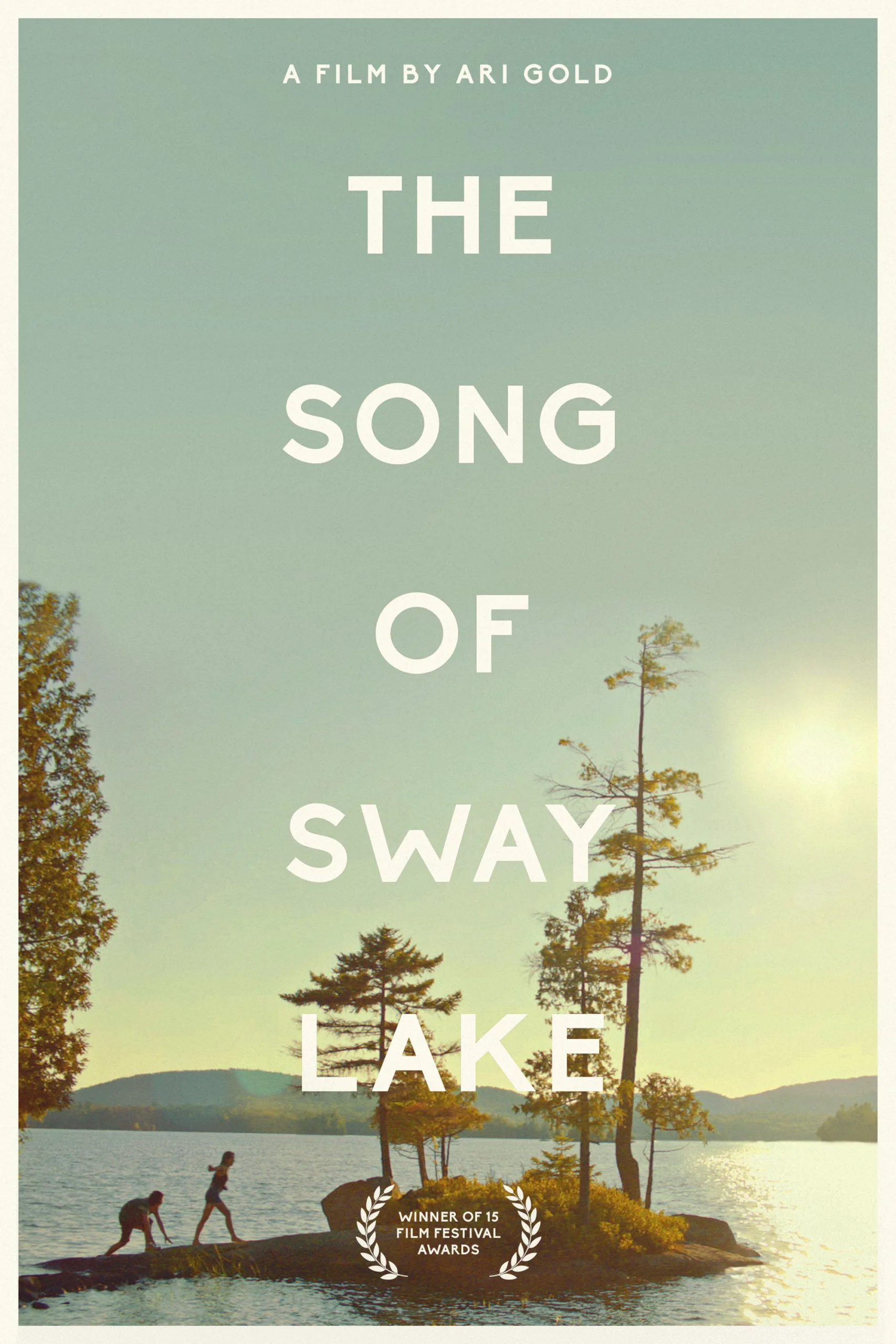

This movie is suffused with golden and near-emerald hues, from its very beginning. There’s an idyllic skinny-dipping scene, set, the viewer will infer, in Sway Lake. And the beauty of the bodies, a male and a female, and the quality of the sunlight coming through the green but hardly sickly water is intoxicating indeed.

“The Song of Sway Lake” never gets anywhere near that heady again. In narration, it tells of both the lake and the song, a catchy tune made popular by a female vocal group in the era of 78s. The family after which the lake is named is, over the years, an unhappy one, and, in 1992, young man Ollie Sway (Rory Culkin), accompanied by a feisty Russian pal named Nikolai (Robert Sheehan), plans to storm the family’s magnificent lake house, from which he intends to steal a rare recording of the song.

Sounds like a flimsy pretext for a movie plot and it is, even if writer/director Ari Gold (yeah, that’s his real name; his father was the novelist Herbert Gold, who was also an academic colleague of Vladimir Nabokov) uses it to wax peripherally philosophical on the lures of recorded music, and Ari’s musician brother Ethan, responsible for the soundtrack, uses it to construct some reasonably credible pastiches of period music.

In most other respects, the movie comes off like a severely unfocused coming-of-age story. Thinking they’re breaking into an abandoned home, Ollie and Nikolai find some attractive locals on the property, whom they shoo off, but not before making note of one of the most attractive of them, a young woman who calls herself Isadora (Isabelle McNally), after whom you’ll never guess.

Then Ollie’s grandmother (Mary Beth Peil) and housekeeper (Elizabeth Peña) show up. The grandmother seems a hardy old goat, one making vocal opposition to the noisy jet skis and rapacious land development plans overrunning the lake that bears her family name. But she’s also snooty, secretive, genuinely contemptuous of the locals. The movie veers listlessly between the poles of its story, never alighting satisfactorily on any of them.

Gold seems most enthusiastic about the record-collector wonk stuff. Ollie fondly remembers his suicide father’s analog enthusiasm: when the needle hit the groove, dad used to say, there was a “crackle you could live in.” When Ollie slaps a 78 on the hi-fi, he raves, “Listen! Just listen! His voice is off key—it’s not perfect—that’s why it’s better!” You know, there are dozens of vinyl fanatic internet forums where I could read a higher grade of this kind of fulsome blather. I don’t need a movie to experience it.

In addition, I think there should be an indefinite moratorium on male filmmakers building shrines to the wounded-puppy look they got on their faces when they went to a party once when they were teenagers, and walked in on the girl they “liked” making out with another guy. In “The Song of Sway Lake” and so many other pictures, such a scene serves no other purpose except to underscore, finally, not so much the pain of awkward adolescence but the perpetual obnoxiousness of teenage boy entitlement. “How dare she?!”

The attractiveness of the scenery, and a quiet, dignified performance by Ms. Peña in what could now be her last movie appearance, wind up being the main redeeming values here.