Set mostly in a hyper-desolate Native American reservation town in Minnesota, Jack Pettibone Riccobono’s “The Seventh Fire” centers on two sometimes reprehensible but extraordinarily vivid men. Rob Brown, whose tribal name is Two Thunderbirds, has spent many of his 37 years incarcerated and will soon head back to prison, leaving behind a pregnant girlfriend. Kevin Fineday Jr., approaching his 18th birthday, looks up to Rob and almost seems like his younger self: by all indications, he’s headed for a life of crime, prison and gang activity. He too has a pregnant girlfriend.

Roger Ebert famously described movies as “empathy machines,” and Riccobono’s film is a powerful example of cinema’s ability to grant even the diciest of characters their full humanity. Described in a newspaper article or crime report, Rob and Kevin would inevitably be reduced to two-dimensional types, self-serving lowlifes who contribute nothing to society and are held in contempt even by some closest to them. While not excusing their behavior, “The Seventh Fire” lets us see both men as complex figures with recognizable feelings and a poignant sense of their own failings and aspirations.

The film has three credited writers (Riccobono along with co-cinematographer Shane Omar Slattery-Quintanilla and editor Andrew Ford), yet it is also nominally a work of nonfiction. Though that may seem a bit contradictory, it captures the film’s sense of comprising a work of “faction,” forging a drama out of real-life materials. Filmed in catch-as-catch-can verite style, it dispenses with documentary techniques such as titles and narration in order to immerse us into its subjects’ lives.

One result of this approach is that its early sections especially feel a bit scattershot. It takes a while of weaving into Rob and Kevin’s intertwined lives over a period of months to begin getting a sense of what makes them tick. Yet the dead-end quality of life in Pine Point village—or “P-Town” as it’s known—on the White Earth Indian Reservation is evident from the outset. It’s a bleak place of identical cheaply made houses, where residents who want dispense with unwanted furniture simply put it on the curbside and set it on fire.

No wonder the main recreational activity for many locals seems to be taking drugs. This is where Kevin intersects with the community professionally. He’s a new, aspiring part-time dealer, who buys and sells and partakes himself. (The film contains several scenes of drug taking.) Though one motivation may be financial, this also seems a matter of image and identity: it gives him a macho role to play around his peers, and Kevin, with his shades, fancy haircuts and hip-hop threads, is nothing if not image-conscious. The ubiquitous posters of De Palma’s “Scarface” here provide an archetype for the narco-thug as a role model for dispossessed young men.

Kevin’s home decorations and taste in tattoo imagery show he also has an awareness of his Native heritage, which in turn suggests that, culturally and perhaps morally, he exists in a divided, conflicted mental space. And indeed, he says he can imagine himself going straight and building a normal life. Yet these words seem like wistful daydreams, while reality is pulling him in a darker, easier direction. His father, evidently having been betrayed too many times, damns him as a liar beyond the pale. “Even when he tells the truth, he’s lying,” Kevin Sr. bitterly scoffs.

Rob leads a similarly divided life, one that shows the unhappy destination that Kevin will reach if he continues on the same road. He’s the product of a ruinous upbringing, and here the reviewer must note one of the peculiar advantages of reviewing films on DVD. In a scene where the film very briefly glimpses a document concerning Rob’s criminal history, I paused the image and read the document’s detailed account of the sexual abuse he suffered as a child, and his subsequent misfortunes in being shuttled through a long succession of foster homes. While this history hardly justifies his criminal career, it does point to reasons he would have been involved with a criminal gang called the Native Gangster Disciples from an early age.

(A side note: Gang activity is alluded to frequently in “The Seventh Fire” but seldom shown. This is presumably because the filmmakers couldn’t gain access to other gang members that they did to Kevin and Rob.)

Up close, Rob seems a solid guy, never malicious or overtly menacing. Photos of him in Native costume as a young man suggest pride, geniality and hopefulness, qualities which have been hardened but not erased by the time he’s facing his fifth trip to prison, for a stay that will keep him inside for over two years. When we follow Rob into the joint, we get to see a facet of his personality that we’ve only heard mentioned before: He’s an aspiring writer, and his words have the power of conviction and a keen awareness of his life’s tremendous challenges and painful lessons.

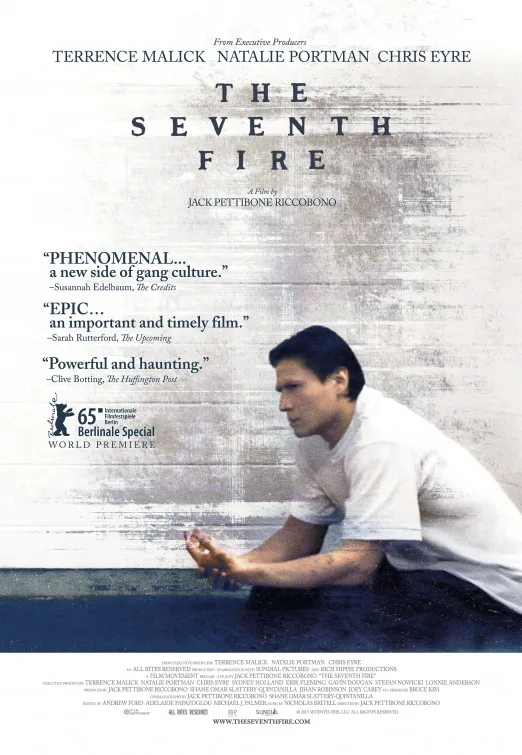

“The Seventh Fire” (the title refers a prophecy of the Ojibwe tribe) has a list of executive producers that includes Natalie Portman and Terrence Malick. The latter’s influence can perhaps be discerned in the film’s disjunctive, impressionistic narrative and its visual vocabulary, which mixes lyrical views of snow and fields with sternly realistic looks at this world’s grim disarray. But whatever other filmmakers may have had an impact on Riccobono, the film’s indelible depiction of current Native life is an achievement that belongs to him alone.