When you can’t escape and you depend on others, you learn to cry by smiling.

So says Ramon Sampedro, who has been in the same bed in the same room for 26 years, not counting trips to the hospital. He was paralyzed from the neck down in a diving accident as a young man. He has his music, his radio and television, his visitors, his window view. He can control a computer, and write using a pen he holds in his mouth. He is cared for by his family, which loves him, and welcomes the money they get from the government for his support. As “The Sea Inside” opens, Ramon demands the right to die.

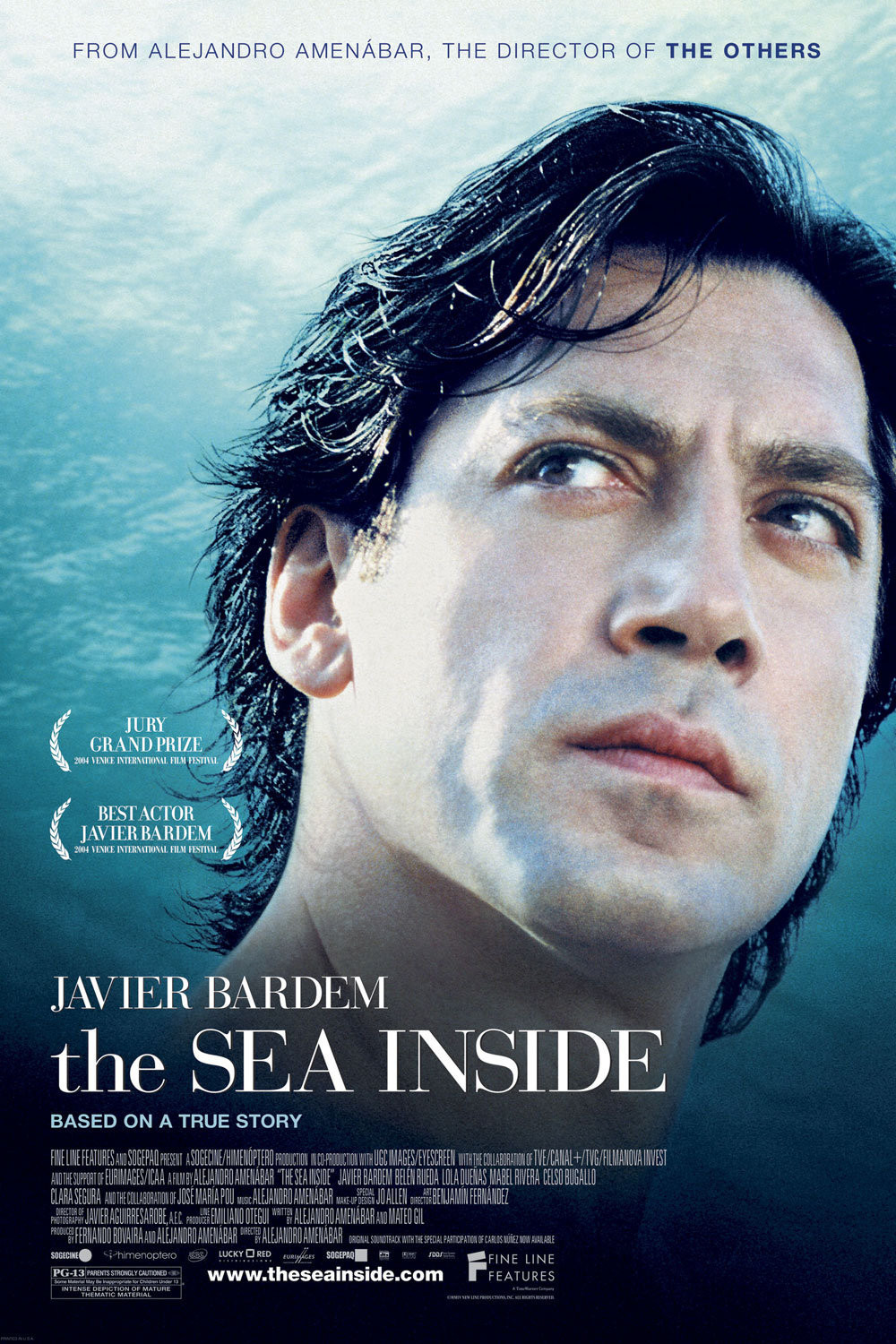

“A life in this condition has no dignity,” he says. He is tired of his bed, his limitations and his life. He argues his point with great conviction, aided above all by his smile. Ramon is played by Javier Bardem, that Spanish actor of charm and gentle masculine force, and the smile lights up his face in a way that isn’t forced or false, but sunny and with love. People truly care for him — his brother and sister-in-law, his nephew, the lawyer from a right-to-die organization, and Rosa, the woman from town who works as a disc jockey and pedals her bike out one day to meet him. Those who love me, he lets them all know, will help me to die.

“The Sea Inside” is based on the true story of a quadriplegic from Galicia, Spain, who in 1998 did succeed in dying, after planning his death in such an ingenious way that even if all the details were discovered no one could be legally charged with the crime. What we see in “The Sea Inside” is fiction, based on the final months. His lawyer, Julia (Belen Rueda), is herself suffering from a degenerative disease, and he feels that will make her more sympathetic to his cause. They fall in love with each other. The local woman Rosa certainly loves him. His family loves him and doesn’t complain about the burden; his brother, in fact, is adamantly opposed to euthanasia. Ramon waits in his bed, smiles, is charming, and figures out how this thing can be made to happen.

Bardem and Alejandro Amenabar, the film’s director, are adamant that they do not believe everyone in Ramon’s position should die. This is simply the story of one man. Yes, and on those terms I accept it, and was moved by the humanity and logic of the character. But it happens I know a few things about paraplegia, which I hope you will allow me to share.

At the University of Illinois, my alma mater, there are more students in wheelchairs than at any other university in the country (the campus is completely lacking in hills, a great convenience), and they were in all my classes; when I was editor of the student paper, our photo editor was in a chair. The most outspoken student radical on campus could walk only with an exoskeleton of braces and crutches — it would have been easier in a chair, but not for him. Among other paraplegics I have known, a lifelong friend recently retired as a sportscaster; a young woman was largely responsible for getting the Americans with Disabilities Act passed, and I once joined a dozen wheelchair athletes on a teaching tour of South Africa. A high school classmate was paralyzed in his senior year; a few years ago I got news of his romance and marriage. Some of these people have had children, and have raised them competently, lovingly, and well. I remember the remarkable Heather Rose, whose condition limited her to the use of one finger, which she used to tap on a voice synthesizer. She wrote and starred in “Dance Me to My Song,” and flew from Australia to attend my first Overlooked Film Festival. Only recently I got an e-mail from a fellow film critic I have been in communication with for years; discussing this movie, he revealed to me that he is a quadriplegic.

These people are all functioning usefully, and it is clear they have happy and productive days, no doubt interrupted sometimes by pain, doubt and despair. To be sure, most of them are not quads. But whatever their reality, they deal with it. Ramon, on the other hand, refuses to be fitted with a breath-controlled wheelchair because he finds it a parody of the freedom he once had.

What would I do in the same situation as the man in Spain? I am reminded of something written by another Spaniard, the director Luis Bunuel. What made him angriest about dying, he said, was that he would be unable to read tomorrow’s newspaper. I believe I would want to live as long as I could, assuming I had my sanity and some way to communicate. If I were trapped inside my mind, like the hero of Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun, that would be another matter — although consider the life of Helen Keller.

In “The Sea Inside,” Ramon Sampedro has considered all these notions, and is not persuaded. He does not care to live any longer. Julia, the woman from the right to die agency, supports him, and so do “backers” from around the country. Rosa, the local girl, desperately wants him to live. A quadriplegic priest visits to talk Ramon out of his decision, and there is a macabre scene in which messages are carried up and down stairs between the two men. Julia’s own health becomes an issue.

What finally happens to Ramon Sampedro I will not say. The movie invites us to decide if we are pleased or not. I agree with Ramon that, in the last analysis, the decision should be his to make: to be or not to be. But if a man is of sound mind and not in pain, how in the world can he decide he no longer wants to read tomorrow’s newspaper?

My friend the sportscaster has written an autobiography, The Real Tom Jones: Handicapped? Not Me, available at online bookstores.