“The River Niger,” a film about a series of crises in an American black family, has good intentions and several very well-acted scenes. But its direction is a mess, and its story falls victim to what might be called the Billy Jack Syndrome. That’s the syndrome, inspired by the movie of the same name, requiring a serious film to be serious about everything – to grapple with all the social issues the author can possibly work in. “Billy Jack” ranged from civil rights to gun control to ecology, with many a stop in between, and “The River Niger” is scarcely less ambitious. We’ve had, by the time it’s over, so many confrontations, so many courageous stands, so much soul-searching and so many issues that we’re overwhelmed.

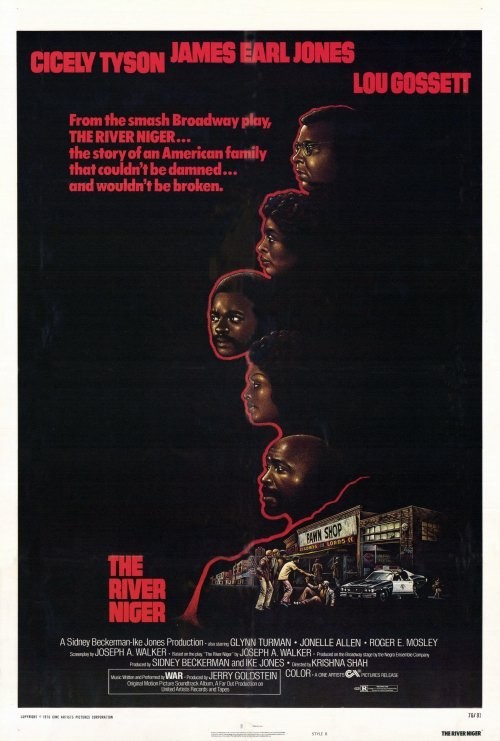

The movie concerns a few days in the life of the Williams family in the Los Angeles ghetto. The father (James Earl Jones) is a painter, enthusiastic drinker, visionary and poet. The mother (Cicely Tyson) is sensible and long-suffering. The grandmother (Hilda Haynes) has license to be a character: She sleep-walks in search of her bourbon bottle. And the son (Glenn Turman) is expected home any day from the Air Force. Before he returns, his fiancee arrives at the home and introduces herself. She’s from South Africa, she says – although she doesn’t explain how or why she got to the United States, and maybe that’s just as well. Given the weight of the other issues about to be considered, the movie’s not ready for the South African problem. Members of the son’s old pseudo-revolutionary street gang turn up, too, and one of them makes a half-hearted assault on the girl, apparently for no better reason than to inspire histrionics.

But we’re only getting warmed up. Before the movie’s over, the son will have revealed he flunked out of flying school, the father will have ranted and raved and gone on a five-day drunk, the mother will have discovered she has incurable cancer, the gang will have gotten into a confrontation with the police and holed up in the Williams’ living room, surrounded, and the father will have returned home in time to read an epic poem and sacrifice himself for either the revolution or his family, it’s not clear. As a play, “The River Niger” won a Tony and a Pulitzer, but the movie doesn’t show why. Events take place so arbitrarily and are considered so superficially that the movie looks more like a year of soap opera crowded into one film. That’s mostly the fault of playwright Joseph A. Walker’s screenplay I suppose, but the direction by Krishna Shah is just terrible. He has no feel for the tone of a scene, he encourages his performers in shameless overacting and he can’t tell his story confidently or clearly. The scenes that work best are the ones where the actors are left more or less alone. Jones and Cicely Tyson have a confrontation during the preparations for their son’s welcome home party, and we believe they know, love and tolerate each other. The family doctor (Lou Gossett) also has some fine, understated scenes with Miss Tyson. And Jones’ reading of a poem about the River Niger – comparing the African river to the black race – is eloquent in its simplicity. But for the rest, the film just doesn’t ring true to human experience; it’s all too obviously a showcase for its unbelievably complicated situations. Think how real, powerful and moving Jones was in a film like “Claudine” – and then see him here, trying to construct a character out of confusion.