Peter Parlow’s “The Plagiarists” is a strange cat indeed. There’s enough provocative material here to warrant a recommendation, yet none of it quite works in the way it was intended. The film is an intellectual exercise masquerading as an indie comedy, and though it didn’t make me laugh once, it sure gave me plenty to contemplate. This is the sort of picture that is more fun to discuss afterward than it is to actively watch. I got more enjoyment from reading Parlow’s exceptional interview in the production notes than I did from any given scene in the movie, some of which are so murky, they border on incoherent.

Lensed by editor/co-writer James N. Kienitz Wilkins on a Sony BVW-200 camera equipped with a Betacam SP videotape, the film deliberately utilizes outdated technology from the 1980s to mimic micro-budget productions routinely praised for their authenticity, from Dogme 95 classics to the diverse array of character studies notoriously labeled as “mumblecore.” According to its official synopsis, Parlow’s feature was conceived as “a playful critique of the mannerisms” that characterize indie filmmaking, allegedly resulting in “the casual perpetuation of stereotypes.” It executes this premise by inviting us to guffaw at its own shallow caricatures of self-involved millennials, whose incessant whining makes the slim 76-minute running time feel at least twice as long.

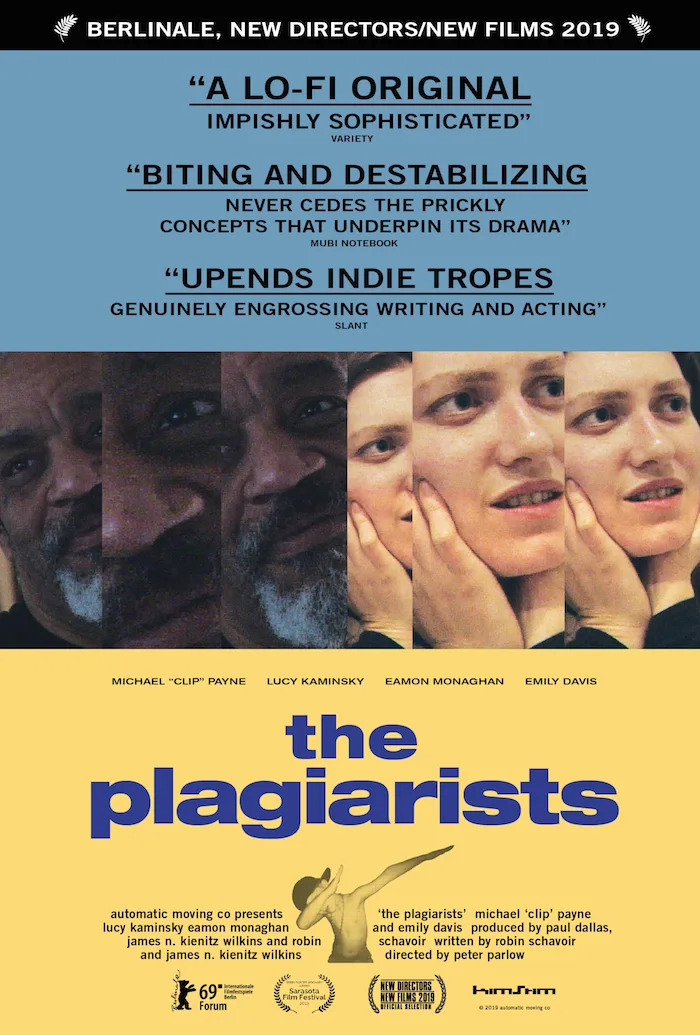

“You gonna roll your eyes,” says Clip (Michael “Clip” Payne) to the unidentified youngster glued to an iPad upstairs in the seconds before he invites two strangers, would-be filmmaker Tyler (Eamon Monaghan) and aspiring novelist Anna (Lucy Kaminsky), into his home. Since the kid still has his headphones on, Clip’s line seems to be directed more at us, the audience, in the first of numerous on-the-nose instances where the script co-authored by Wilkins and fellow visual artist Robin Schavoir breaks the fourth wall. No sooner has Clip made this promise than the young couple bursts through the door, sardonically dubbing themselves “the city people everyone complains about.” With their car broken down, Tyler and Anna are only too happy to take Clip up on his offer to spend the night at his place, despite their racially fueled trepidation.

The couple’s whiteness quickly emerges as one of their most glaring features, causing them to flinch at the mere sight of a black man later on in the film, simply because he reminds them of Clip, even with his back turned to them. As played by Payne, a longtime member of the Parliament-Funkadelic collective, Clip is endowed with a soothing voice that both draws us in and heightens our suspicion, playing into our expectations molded from endless contrived plots where lovers are lured into a trap by a kindly elder. The disconnect between Payne and his co-stars is apparent from the get-go, since he never shares the same frame with them. That’s because his scenes were shot separately, thus preventing him from ever developing a natural chemistry with Monaghan and Kaminsky, who often appear as if they are talking to themselves.

Adding to the nagging strangeness of the proceedings is a monologue delivered by Clip toward the end of the first act to an awe-struck Anna. It is jarring not because its sublimely articulated recollection of youth is, as Anna judgmentally notes, “uncharacteristic” of Clip’s language, but because Payne’s affect is so flat that he appears to be reading off a teleprompter (and apparently was, according to Parlow). This choice, while audacious, strikes me as a miscalculation since it further renders what could’ve been an intriguing character into an enigmatic prop. We get little sense of what meaning these words held for him or why he bothered committing them to memory, since it’s revealed months later, at the top of the second act, that Clip lifted them directly from Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle, Book 3: Boyhood. The inclusion of halo-like backlighting and hokey stock music found on Pond5.com, the non-diegetic nature of which breaks Dogme 95’s vow of chastity, only adds to the surreal quality of Clip’s plagiarized speechifying.

I couldn’t help being reminded of a friend who became disillusioned upon learning that her high school mentor took credit for a pre-existing monologue, seeking unearned validation from her students by making it seem as if she had written it herself. This breach of trust can lead to a shattering sense of betrayal, especially when it is triggered by the deceptions of an adult role model. Yet in the case of Anna and Tyler, why are they so alarmed by a lie as harmless as Clip’s? Is it the realization that they may never be capable of creating work as vivid and profound as what he chose to recite? Or is it a more insidious sense of indignation over a black man feigning ownership of a white author’s thoughts? Since cultural appropriation reverberates through the entire history of American life, the couple’s moral outrage boils down to sheer hypocrisy.

Suddenly, Clip is blamed for all the couple’s subsequent misfortunes, prompted by Tyler’s loss of an Evian contract after his busted car caused him to lose a day of filming on their latest commercial. Outraged that Clip fell short of embodying the angelic, oft-recycled trope referred to by Spike Lee as the Magical Negro, Tyler claims they’ve been cursed by a “black magician” who runs a “DIY daycare center executive produced by Morgan Freeman.” This is one of many lines Tyler punctuates with a self-satisfied chuckle, while faced with deadening silence, not to mention consternation from their friend Alison (Emily C. Davis), who insists that she is only a casual acquaintance of Clip.

This assertion is somewhat refuted by the imagery that materializes during the film’s epilogue, as we hear Alison in voice-over, reading a letter she has penned to Anna, encouraging her to complete her memoir. Though her words have been largely borrowed from a Guardian essay arguing that books are better than cinema, unlike Payne’s stilted reading of the Knausgård text, Davis infuses the lines with such conviction that we barely realize in the moment just how inane they are, particularly when the revelations contained within the footage result in a sensory overload. As Wilkins noted during an interview with Filmmaker Magazine, “A very vapid assessment of film versus literature can take on depth if you’re steamrolled by it.”

“The Plagiarists” is a deeply frustrated film that is often frustrating to watch, yet it is most rewarding as a meditation on the obstacles modern day artists must contend with when living paycheck to paycheck. Among Parlow’s chief targets is the delusion that a corporation can assist in realizing a director’s dreams, as evidenced by the laughable Coca-Cola Regal Films shorts preceding the public screenings at Regal Cinemas, where student filmmakers are invited to “showcase their talent” with a 30-second ode to the joys of coughing up spare change for overpriced concessions. Concerns of a fiscal nature, rather than an ethical one, are what Parlow believes guide all aspects of the marketplace, and that includes the criminalization of plagiaristic acts, even those committed without monetary gain.

A great many questions are left unanswered here, and that is obviously by design, since Clip is used primarily as a scrim upon which Anna and Tyler can project their preconceptions. After all, what motivates the choices made by someone we don’t know are not for us to define. It’s also no accident that the film’s title is a plural noun, not only since Alison appears to have inherited her friend’s knack for copying and pasting, but because Parlow ultimately suggests that as members of the 21st century, we are all plagiarists feeding into an online pool of co-opted ideas. It’s a powerful statement that is worth exploring. If only the film had characters on the level of its thesis. So aggravating are these Gen Y Bickersons that when Justin Chang’s review of “You Were Never Really Here” began playing on their radio, it upstaged their banter to the point that I wished they’d simply shut up and savor the analysis.