Up until now, the Scottish writer/director Armando Iannucci has shown a deft, almost feral facility in depicting characters who act with both casual and calculated cruelty. And he’s placed these vulgar, coarse monsters and demi-monsters in the corridors of power, where they can inflict damage not only on each other but on the world at large.

His British series “The Thick of It” was a dizzying treatment of the spin doctors around Downing Street; the HBO series “Veep” took its horrific pleasure in the swamps of D.C. The 2009 movie “In the Loop,” spun off of “Thick of It,” brought the hammer down on U.S. and U.K. leaders unleashing the dogs of war mainly to satisfy their own vanity. As an indirect indictment of the war in Iraq it was in the end more heartbreaking than hilarious. And then there was 2017’s “The Death of Stalin,” perhaps his most mordant burlesque. Some might call Iannucci a cynic, but one need merely look about the world today to see he’s more of a realist with an edge. (And that his realism has been lapped by reality.)

So one of the things that’s most surprising about his new picture, which he co-wrote with Simon Blackwell—is its life-affirming sunniness. Yes, as you likely know if you know the source material, its hero, the most autobiographical in Charles Dickens’ body of work, does go through it. The narrative offers up two major villains, one David’s cruel stepfather, the other the sniveling cheat Uriah Heep. Neither of these figures, bad as they are, approach the near-gothic characteristics of the likes of Fagin and Bill Sykes of Oliver Twist, however. And “Copperfield” counters its malefactors with some of Dickens’ most delightfully eccentric characters. An amiably dotty aunt, a distracted cousin, the eternal optimist Mr. Micawber, and more.

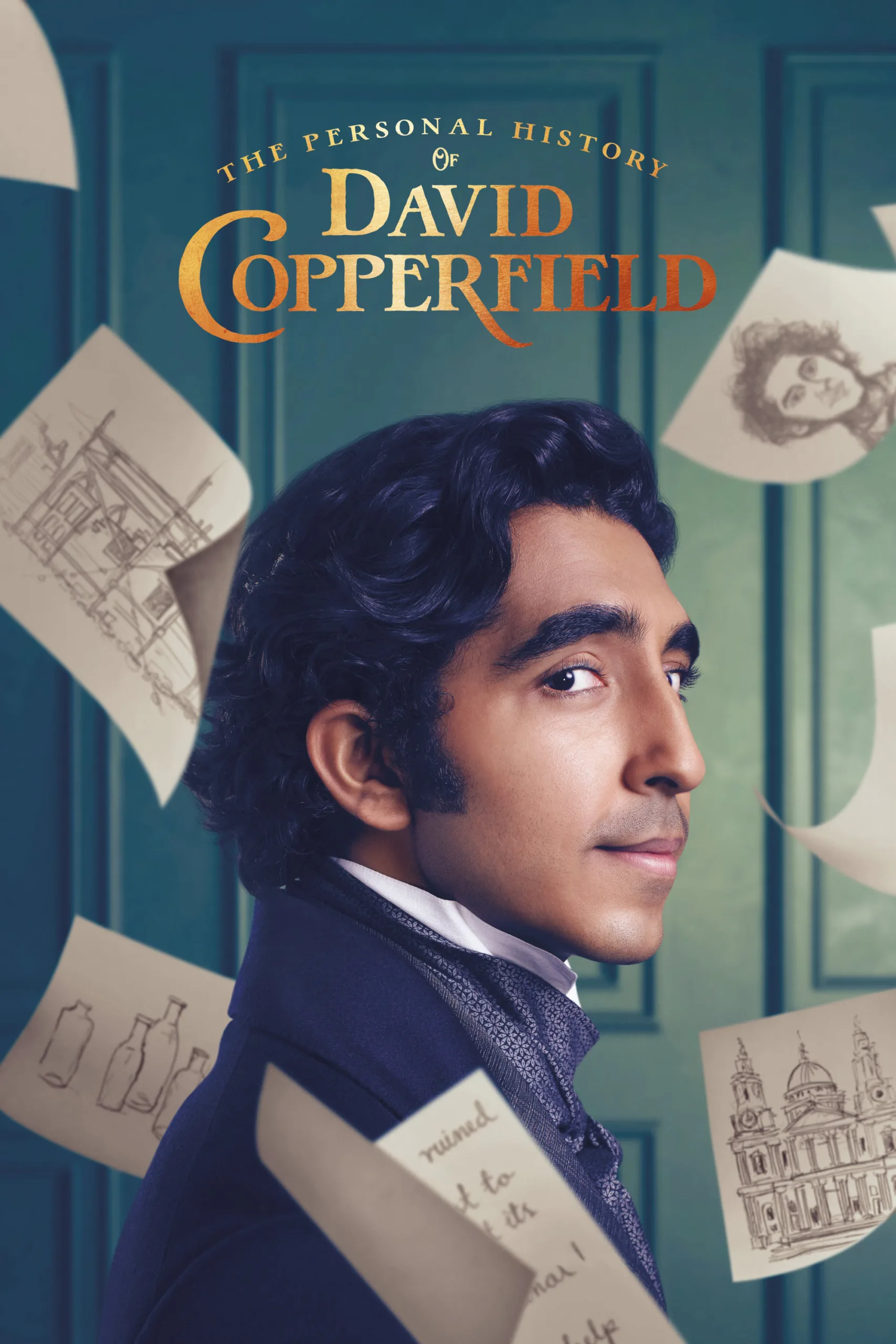

Iannucci begins by making it clear that, despite the casting of Hugh Laurie, Peter Capaldi, and other stalwarts of classic BBC fare—and of course Laurie and Capaldi are Iannucci veterans as well—this is not your “Masterpiece Theater” Dickens. Many will take special notice of the multi-ethnic casting, starting with Dev Patel in the title role. All I want to say about it is: why not? All fiction is circumscribed by its creator, or in this case by its adaptor, and why shouldn’t persons of color be able to see themselves portrayed as central characters in a fictionalized mid-19th-century England?

The other ways Iannucci breaks things out are more immediately noteworthy. As Copperfield is the narrator of his own story—the first scene shows Patel’s adult David delivering his story in a theater, as a monologist of sorts—so Patel’s David can turn up looking on as his mother gives birth to him. Moving camera, onscreen texts, drawings that almost come to life, slapstick that drags Dickens into Charlie Chapin territory—there’s a bit when Micawber’s creditors come to repossess his furniture, involving a long rug pulled from behind a door, dragging chairs and tables and dinner along with it—it’s all in there. “Copperfield” is a grand, long novel, and in reducing it to 120 minute scale, Iannucci has hewn it to something almost anecdotal.

It works a treat for the most part—and in no small part due to the contributions of cinematographer Zac Nicholson, costume designers Suzie Harman and Robert Worley, and a large production design/art direction team featuring Charlotte Dirickx. In a scene where David works with Hugh Laurie’s Mr. Dick to try and get him over his obsession with the beheading of Charles the Second, which interferes egregiously with Dick’s memoir-writing. David wears a deep aqua-blue vest and trousers of a particularly wide gray-and-tan check; Mr. Dick has a neckerchief striped pink, and so on. You almost miss the scene for being dazzled by such clothes. Once they’ve come up with an activity to alleviate Mr. Dick’s obsession, they go downstairs; the yellow fabric in front of the house’s two front windows almost upstages Betsey Trotwood, who’s played by Tilda Swinton—someone we all know is hard to upstage.

Iannucci’s conception feels breathtakingly original, until about an hour in, when he breaks out silent-movie style fast motion, and you realize, yes, he definitely looked at Tony Richardson’s “Tom Jones” before embarking on this project. No big deal—more period filmmakers should do likewise.

What it all builds up to is a boisterous hymn to the creative impulse—David does grow up to be a great writer, after all—and a celebration of memory and imagination. Of the place in the heart where, as David notes near the end, “loss and love live, forever side by side.”