“Any comic who says they’ve never bombed onstage, they’re not being real about what we do.” – Cedric the Entertainer

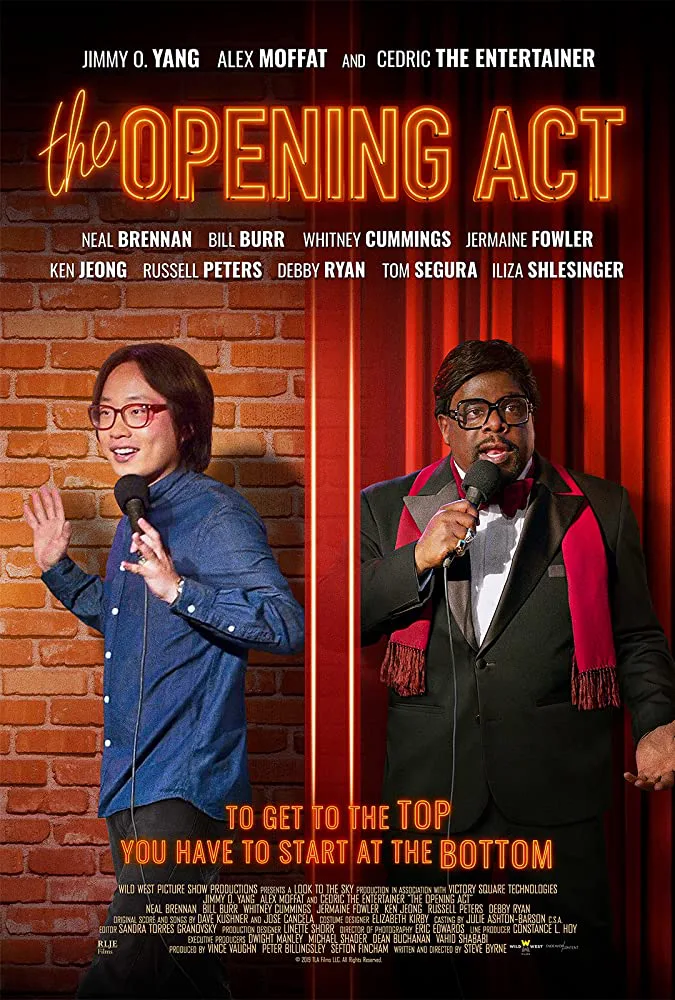

Some fathers and sons bond through sports. Some bond through fishing. Some bond about books, cars, opera. It doesn’t matter, as long as bonding happens! In “The Opening Act,” written and directed by comedian Steve Byrne, Will Chu (Jimmy O. Yang) and his dad bond through their love of standup comedy. The film starts with a montage of Will’s childhood, showing Will and his dad at various ages sitting on the couch and laughing uproariously at comedy specials. This is a beautiful way to start. A lot of different factors go in to making someone successful in comedy, but an aspect not often discussed is perhaps the most important: self-knowledge and self-awareness. Who are you and what is your point of view? “Opening Act” takes place over a four-day period where Will, during his first big paying gig, faces a steep learning curve about who he is, why he wants to “do comedy,” and what he needs to do to get better at it. It’s a very insightful insider-baseball look at the creative process.

Will works a nine to five job at an insurance company, he has a nice girlfriend (Debby Ryan), but he’s stagnating. A couple nights a week he goes to a local comedy club and begs for a slot in the night’s lineup. When he gets onstage, he does well, people laugh. He’s a good kid, maybe a little bit idealistic, but he’s hungry, too. When a break basically falls into his lap, he quits his job and heads to Pennsylvania to emcee a weekend of shows at a famous comedy club. The headliner—a comedian named Billy G. (Cedric the Entertainer)—is one of Will’s idols. Will can’t wait to meet him.

Things don’t go as planned.

The film is broken up over the next three days where Will is thrust into a very intimidating world. His name is spelled incorrectly on the marquee (“Will Chew”). He tells someone it’s wrong. Nobody cares. (This joke pays off at the end. Everything Byrne sets up in beginning scenes has its payoff in the end. “The Opening Act” is deeply satisfying on that level.) Will’s roommate for the weekend is another comedian on the bill, Chris (Alex Moffat), who may be a womanizing party-hound, but he also takes Will under his wing professionally, showing him the ropes. (He also involves Will in some drunken shenanigans, with disastrous results.) When Will nervously introduces himself to Billy G, ready to tell Billy G how much his work has meant to him, Billy G. cuts him off, giving him extremely specific instructions on how to introduce him to the stage. Will botches Billy G’s intro, and is so unnerved by the whole experience he then bombs during his own set. He bombs during a radio show interview. He keeps bombing. He has suddenly become the least funny person in any room, ever.

Getting over this isn’t easy, and getting over this, the film suggests, is what being a standup is all about. Every comedian bombs. You either recover and try again, or you give up. What is refreshing about “The Opening Act” is that it is about the process of “getting better” at something, through trial, error, trial again. The creative process is very difficult to show on film. Most of the creative process is boring and repetitive: a person writing at a desk for hours, a person practicing for hours, doing the same thing over and over again. It’s easier to show triumph magically arising out of, oh, a person “believing in themselves” all of a sudden. The reality is much more painstaking, and “The Opening Act” takes the time to get into it.

Byrne has filled the cast with standup comedians and writers: Bill Burr, Ken Jeong, Tom Segura, Neal Brennan, Alex Moffat, Bonnie Hellman, Russell Peters, all of whom play cameo roles. You can tell that “The Opening Act” was written by someone who knows the field intimately, and much of it feels semi-autobiographical. When comics sit around and “talk shop,” they don’t revel in their triumphs. They commiserate on the moments they bombed, or dealt with horrible hecklers, or didn’t have enough material to fill their time slot, of hearing “crickets” after you tell a joke you thought was a real banger. Those hard times help a comedian to toughen up, and—most importantly—listen to the audience, figure out why a joke didn’t work. It’s not the audience’s fault. It’s yours. The joke may be funny but you haven’t worked out how to tell it yet. This is the process “The Opening Act” takes time to show. For example: Since Will is from Ohio, rowdy hecklers chant “OHIO SUCKS, OHIO SUCKS” every time he starts his set. Will is completely dominated by the hecklers. He has no way to combat them. Until he figures out a way. This is one of the film’s many payoffs.

The biggest payoff though is the development of the relationship between Will and Billy G. Billy G is an industry giant, with a popular television show and a best-selling book. Will has to work to overcome the horrible first impression he made. This is the unofficial “cliffhanger” of “The Opening Act,” and when those two finally come together, it practically justifies the film’s whole existence. Cedric the Entertainer works at such a high level as an actor, with such specificity, and yet he does it without “showing” how hard he’s working. Nothing is random: every gesture, every ring, every hat, every expression, how he eats his soup, how he walks, is carefully chosen, and yet nothing feels artificial. He’s a great character actor. When Yang looks at him with awe, hanging on every word, you feel the same way. These moments of accord are hard-won, and that’s part of the point too.

The ending credits of “The Opening Act” features clips of the comedians in the film—as themselves—talking about times they bombed in their careers. (One says, “I bombed for two years straight.”) To go back to Cedric the Entertainer’s quote at the top of this review, “The Opening Act” is committed to being real about its subject. And in that environment of tough knocks, hostile “crickets,” and mean-spirited hecklers, triumph really means something.

Now in theaters and available on digital platforms