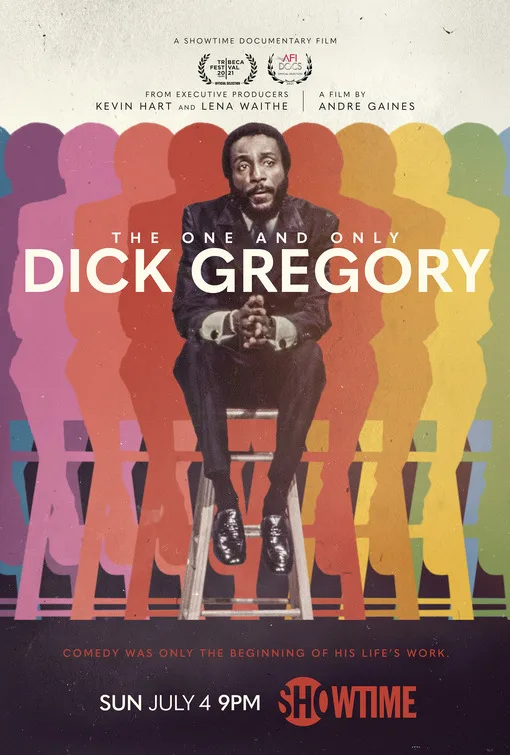

The uncanny confidence of Dick Gregory comes through from the opening minutes of “The One and Only Dick Gregory,” and he becomes more formidable as the film unfolds.

As recounted by New York Times sports columnist Robert Lipsyte, who ghostwrote Gregory’s first book, Gregory’s legend was born in Chicago in 1960 when he was hired as a comic at the Playboy Club. One night, Gregory was told that his audience consisted of visiting white Southern businessmen and that considering the racial tension surrounding the Civil Rights movement at that moment, management wouldn’t blame him if he canceled. Gregory went onstage anyway, and ran the room with such confidence that Time magazine wrote glowingly of his performance, predicting that he was “just getting started on what may be one of the more significant careers in American show business.”

It was the start of something grand. The office of Jack Paar, then the host of NBCs “The Tonight Show,” tried to book Gregory, but Gregory told the booker that he wasn’t interested if it meant he would come onstage, do a few minutes of material, and leave. Gregory wanted to sit next to Paar afterward and have a proper conversation, something no Black comedian had done on “The Tonight Show” until that point. Paar was so stunned by Gregory’s principled refusal that he personally phoned him and gave him what he asked for. The “Tonight Show” appearance made Gregory’s asking price jump. In the space of a few weeks, he went from barely surviving to earning half a million dollars a year.

As writer-director-producer Andre Gaines lovingly chronicles, the biggest and best was still to come—and the truly amazing thing about Gregory’s story was that he didn’t just keep breaking down barriers and becoming richer and more famous. He became legendary for having convictions and acting on them, even when it cost him money, friendships, the intimacy of his family, and the goodwill of white audiences that would’ve preferred a Black performer bring the funny and leave current events behind.

The most moving section of the film focuses on Gregory’s work in the Jim Crow-era South as an organizer and entertainer, motivating marchers, facilitating donations, and lending his name to the cause of Civil Rights. The more bluntly Gregory critiqued the white power structure, including the police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the federal government, the more it impeded his career opportunities, but he didn’t care. He considered it the necessary price for being able to look at himself in the mirror. An audio recording finds him quoting his wife Lillian telling him, “The true test of a rich man is, you strip him of his wealth and see how much he’s worth.”

To that end, Gregory put his life, not just his career, on the line, enduring multiple arrests and a savage beating with bats while marching in Birmingham, and being targeted by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI as an enemy of the United States. Like many prominent individuals who got involved with the movement, he lost friends to murder, including Medgar Evers, who was shot to death in his driveway while Gregory was at home in Chicago grieving the demise of his own infant son, and Martin Luther King, pictured in photographs roaring with laughter at Gregory’s routines and listening attentively to his comments during private conversations.

Nothing that follows that section of the movie has nearly the same emotional power, so it’s questionable whether the documentary needed to spend quite as much time as it does on Gregory’s legal and financial troubles or his work as a nutritionist (which was important, too, of course, but less inherently cinematic). A good portion of the final third of “The One and Only Dick Gregory” takes so much of its structure and information from an Ed Bradley-hosted “60 Minutes” profile that it starts to feel as if you’re watching “60 Minutes.”

Despite these miscalculations, “The One and Only Dick Gregory” is a thoughtful film about a politically committed artist that doesn’t short the politics or the art, but instead examines how one fueled the other, and shows us that Gregory was always political even before he started marching for Civil Rights and becoming friends with soon-to-be-martyred heroes of the movement. Modern-day artists and surviving historical personages from the ’60s contribute deeply-felt observations on Gregory’s craft and substance, including Lipsyte, Chris Rock, Wanda Sykes, Harry Belafonte, and Evers’s widow Myrlie Evers-Williams. Sykes, and Rock are particularly astute, breaking down Gregory’s matter-of-fact tone and relaxed pace (a contrast to other Black comics from the period) and going deep on specific choices, such as the way he used a cigarette to time his setups and punchlines.

Among the film’s most notable achievements is its revival of classic Gregory one-liners that describe America in the 1960s but could just as easily apply to the present. He calls American football “the only place where a Negro can chase a white man and 40,000 people stand up and cheer,” and tells a talk show crowd, “Never clap for me. Just take me to lunch when it’s not Brotherhood Week.”

Gregory’s analysis of modes of performance by Black entertainers hasn’t aged a second. He puts things in perspective (for the past and the present) with more simplicity and elegance, and greater awareness of the complexity of audience response, than most academics and editorialists can manage on their best days. “We weren’t saying take Amos n’ Andy off,” he says in one of many reel-to-reel audio recordings. “We were saying, ‘Balance it out.’ Put the man on [TV] splitting the verbs. But also, let me see my Ralph Bunche. Let me hear my Marian Anderson.”

The editing, by Cinque Norton, Ron Eigen, and Patrick Murphy, achieves an essay-film suppleness and subtlety, making arguments through clever arrangement of images, not just by illustrating whatever a person happens to be talking about. The score, by Kyle Townsend, covers an impressive array of genres, variously situating Gregory within the contexts of blues, funk, Americana/folk, even symphonic classical, and musically driving home the idea that he was not simply a Black American but an American, and a citizen of the world. This approach resonates with King’s comment that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.