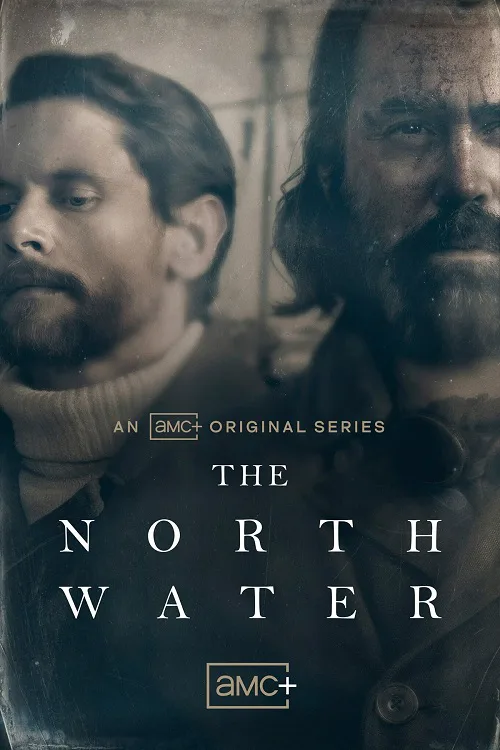

Patrick Sumner (Jack O'Connell) is a disgraced ex-army doctor. Henry Drax (Colin Farrell) is a master harpoonist. The two disparate men, guided by opposing moral compasses, unmoored by uncontrollable vices, are thrown together on a whaling ship bound for the bottom of the ocean. Set in 1859 (eight years after the publication of Moby Dick), Andrew Haigh’s five-episode series “The North Water,” adapted from Ian McGuire’s same-titled novel, begins as a tense high-seas whodunit but later flounders as a survivalist drama.

With films like “Weekend,” “45 Years,” and “Lean on Pete,” Haigh has extracted the profound from the modest. Much as he tries, in “The North Water,” the profound does not exist. At least, not in the way Haigh wants it to.

Sumner arrives in Hull, England—a muddy, grim backwater filled with drunk, horny sailors, testy barkeeps hoisting billy clubs, and ramshackled sex workers—searching for his next job. Weeks ago, while at a hotel bar, the whaling ship magnate Baxter (Tom Courtenay) heard of his predicament: After Sumner’s discharge from fighting with the British Army in India, the young army doctor learned of a tidy inheritance left to him by his recently deceased uncle. It’s just enough land to sell and to form his own practice. Claimants have come out of the woodwork, unfortunately, tying up his estate in court. He needs a gig until his legal woes have passed, something to get him back on his feet. Despite his sincerity, his story is a load of bunk.

Even so, Baxter offers him a job on The Volunteer, helmed by the assured Captain Brownlee (Stephen Graham), supported by the conniving firstmate Cavendish (Sam Spruell). With the help of the two men, Baxter intends to sink The Volunteer, take the insurance money, and leave the fledgling whaling business behind to become an industrialist. No one else on the ship knows about the plan but them. Only Drax might have an inkling.

The problem: Henry Drax is the last man you want with or against you. He’s a cold-blooded opportunist governed by a primordial instinct to kill. A hulking mass of muscle and mangy hair, hidden underneath a bleak brown coat, when Drax walks his breathing heaves like a locomotive. Much as Farrell tries to portray this man of few words, lumbering with a heavy step, the physicality of the oversized character doesn’t come naturally to him. Whenever he walks, it looks like he’s bound to a muscle-constrained suit. Whenever he talks, there’s an eagerness to cover the thin characterization he’s been handed.

For their doomed voyage, Haigh arranges several compelling storylines. Sumner, for example, haunted by the war in India, takes the addictive drug laudanum to dull the mental anguish. For these scenes, a hazy veil washes over the composition. A cabin boy is also brutally raped onboard, an incident Sumner takes upon himself to investigate. Drax and Cavendish plot to kill Sumner, robbing him of his precious emerald-set Indian ring. And Otto (Roland Møller), an autumn-aged deckhand, has a premonition that the boat will sink, and Sumner will live inside of a bear.

The first half of “The North Water” thrives on these intriguing pieces, elucidating the boundaries between good and evil, the saved and the damned, as the crew careens toward disaster like a Greek tragedy. It further hums with an exceptional soundscape, as pinching synths squeal with a whale’s register, and find gruesome contours in the pursuit of whaling and sealing. The hunting sequences, for example, are filled with copious blood as Drax and crew rampage on an icy tundra after unsuspecting seals. First, shooting them to wound. Then bludgeoning them with a pickaxe. Then skinning them. The three-act structure isn’t for those with gentle constitutions. The same goes for Drax’s harpooning skills, which produce plumes of carnage. Throughout, the psychological untethering required for the job shows: How the killing of animals has whittled these men down to total monsters, whose only solace comes when they’re on the hunt.

Other themes explored include the era’s homophobia, the class restrictions that keep men like Sumner and Drax, no matter their respective education levels, down on lower economic rungs, and the “White Man’s Burden” that dominated the 19th century British Empire into believing all people of color were savages and brutes (a theme that recurs in episode four to devastating effect). Likewise, O’Connell, Graham, and Spruell give wonderfully tactile performances as men fighting for their piece of the pie when there is no pie to be had.

“The North Water,” unfortunately, loses steam once the men are trapped on an ice cap. That’s when the series takes many of its beats from Werner Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” as the brutish Cavendish, in particular, fights for leadership. His struggle for power would carry greater weight, as would Sumner’s journey toward peace and redemption, if Drax weren’t so flatly drawn. He is pure evil. And as much as Farrell tries, there are no layers he can add to the character. Instead the series runs aground into Haigh trying to pull profound elements from Sumner when none exists. He’s merely a broken, drug addled man cheated out of the cozy, honorable life he thought was meant for him.

The show’s final shot left me cold. Haigh’s “The North Water” possesses every psychological and humanist component required to elucidate the nature of good and evil, including all of the shades in between, but wastes too much effort trying to discover profound significance rather than fortifying its lackluster characters.

Premieres on AMC+ on July 15th.