“That’s what we’re good at – shopping and talking.” – Dialogue from “The New Age” Peter and Katherine Witner are conduits for vast amounts of money, which flow from their extravagant Beverly Hills salaries into the hands of the people they buy their lifestyle from. They live in a designer house with walls covered by “important” paintings, and their friends are as wealthy as themselves. Their personalities are made out of psychobabble and arrogance; they are obsessed with their toys, but, hey, you’re okay, I’m okay, and that’s okay.

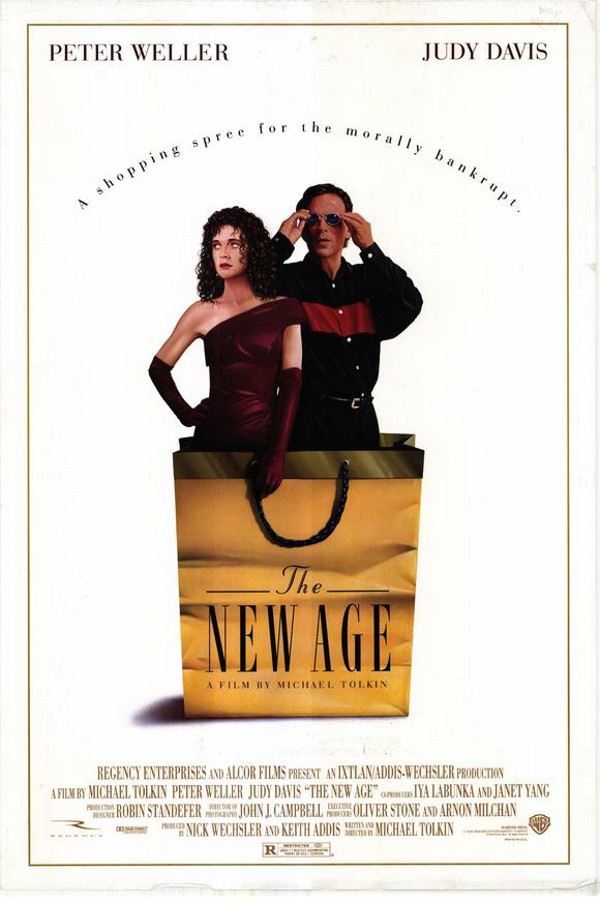

Then one day they both find themselves out of work, with only enough cash in the bank to finance about 30 more days of opulence before the whole structure of their lives comes crashing down. “The New Age,” Michael Tolkin’s film about their dilemma, is a satire, but it avoids making them into easy targets. They’re too vulnerable to really dislike; without their credit cards, they’re like Boy Scouts without any way to start a campfire.

Tolkin knows the world of Peter and Katherine from the inside out, as he showed in his screenplay for “The Player,” another X-ray of the lifestyles of the rich and famous. “The New Age” also has something in common with the 1992 film Tolkin wrote and directed, “The Rapture.” It shows his characters caught up in the search for quick spiritual fixes. As their bank account shrinks, the Witners (played with frightening accuracy by Peter Weller and Judy Davis) turn to a series of gurus whose prescriptions run from meditation in the desert to all-night pool orgies.

This need to believe in something is almost required by the hedonistic lifestyles of the characters. While many spiritual programs advocate humility, the New Age beliefs of the Witners allow them to star as the objects of their own worship. If you feel right about yourself, if you think positive, if you send out the right aura, then success, of course, will come to you. The catch is that failure and poverty are therefore somehow your own fault, too.

At one point in the movie, the Witners are encouraged to get in touch with their own fears, and Peter utters a classic line: “I know what I fear the most. Having to work to make money.” But work they do. The Witners pool their diminishing savings and borrow money to open a trendy boutique. One of their gurus (played by the droll voluptuary Patrick Bauchau) stands in the center of the empty storefront, tuning in to the space, before advising them where to place the dressing room. Opening night is a great party, but soon the store is failing, and the few customers who do wander in are not much encouraged by the Witners’ increasingly bizarre adaptation to the world of retail.

Tolkin gives us one richly detailed set piece after another, involving luncheons, openings, massages, telephone tag, psychic consultations, sex, heartfelt conversation, and pagan rituals led by a bald-headed woman who sees what others cannot see. Meanwhile, the material universe remains the one thing Peter and Katherine can really count on. This is the kind of movie where ancient Chinese sayings can find themselves in the same conversation with co-dependency.

For the Witners, everything centers on themselves. “We were born when the economy was expanding,” Peter says. But now that it’s contracting, there’s no room for people who consider their jobs primarily as a source of money to finance their “real” lives. Down and down they go, the Witners, auctioning their important paintings, losing their house and their cars, failing at business, all the time looking for spiritual fixes, as they wander through the New Age supermarket of Southern California. It’s as if they have a disease named Overdrawn. One former friend of Katherine is frank about why she didn’t invite them to her latest party: It makes people uncomfortable to be around failure.

The ending of the movie is perhaps a bit too manipulative.

Maybe not. Tolkin is a director who is not afraid to push stories to their limits, and the final situation in which the Witners find themselves is one which was a real possibility right from the first.

What’s best about the movie is that Peter and Katherine are so smart.

They understand everything that’s happening, they’re articulate, sardonic, witty and savage about it, and yet there’s not much they can do. “The reason you keep falling,” one spiritual adviser explains to them, “is because there’s no bottom.” Thanks a whole lot.