I recalled his arrest and trial. Ironically, Ellsberg’s case was dismissed because the White House plumbers broke into his psychiatrist’s office and Nixon offered to make Ellsberg’s judge head of the FBI. Said Judge William Matthew Byrne Jr.: “The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.”

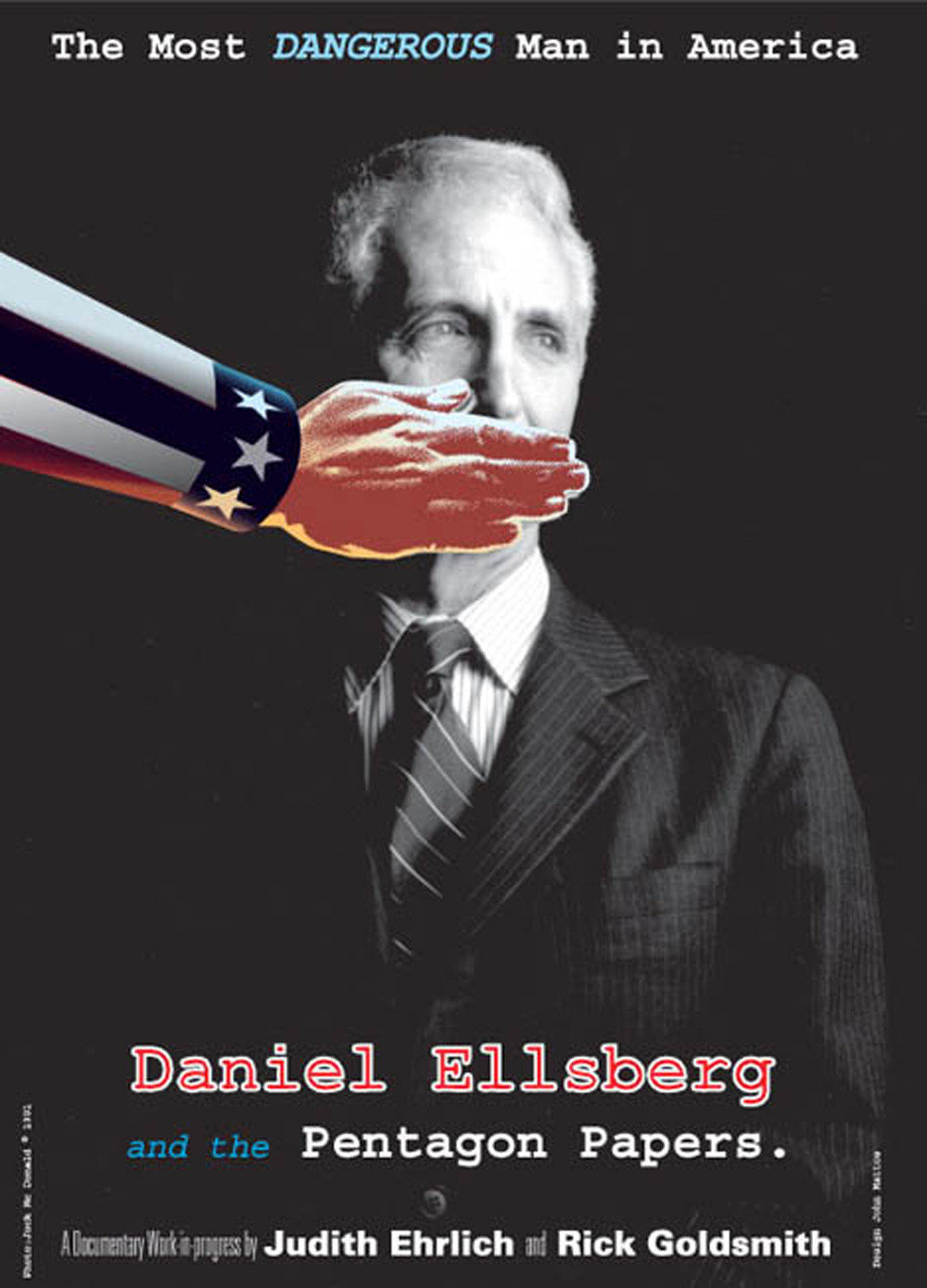

I knew all that. What I never realized was what a high-ranking employee really Ellsberg was and how secret the Pentagon Papers really were. “The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers,” a documentary by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith, explains all this. Locked in safes, the papers’ existence was a secret even from President Lyndon B. Johnson, who, it was believed, would have been infuriated by such a history. Ellsberg didn’t merely leak the papers, he played a key role in contributing to them.

On his first day on the job, cables came in from the celebrated Gulf of Tonkin incident, used by LBJ to justify escalating the war in Vietnam. Later the same day, cables from the commodore in command over the “attacked” ships said there was a “problem” with the reports — which turned out to be false. Johnson, however, didn’t want to hear it. He was ready to escalate the war, and he escalated.

His was the latest in a series of presidential decisions beginning with Truman, and continuing through Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, who financed France in its Indochinese war, propped up corrupt regimes in South Vietnam, prevented free elections and eventually wreaked destruction in an unwinnable war.

Ellsberg, a Marine company commander in the 1950s, wanted first-hand information. He went to Vietnam personally, shouldered a weapon and led a patrol. What he learned convinced him that a false portrait of U.S. success was being painted. On a flight back to Washington with Robert McNamara, the defense secretary agreed that the war could not be won; we see the two men leaving the aircraft together before McNamara lied to the press that America was winning it. Later, McNamara resigned, for reasons he didn’t make clear at the time, and not even later in the confessional documentary, “The Fog of War,” directed by Errol Morris.

Ellsberg, in short, could not be dismissed as merely a sneak and a snitch, but a man who had direct knowledge of how the American public had been misled. He saw himself not as a peacenik war protester, but as a government servant exercising a higher moral duty. “The Most Dangerous Man in America” traces Ellsberg’s doubts about authority back to a childhood tragedy and forward to the influence of young men who went to prison for their convictions.

It is a skillful, well-made film, although, since Ellsberg is the narrator, it doesn’t probe him very deeply. We see his version of himself. A great deal of relevant footage has been assembled and is intercut with stage re-creations, animations and the White House tapes of Richard Nixon, who fully advocated the nuclear bombing of Hanoi. Kissinger was apparently a voice of restraint.

If you can think of another war justified by fabricated evidence and another Cabinet secretary who resigned without being very clear about his reasons, you’re free to, but the film draws no parallels.