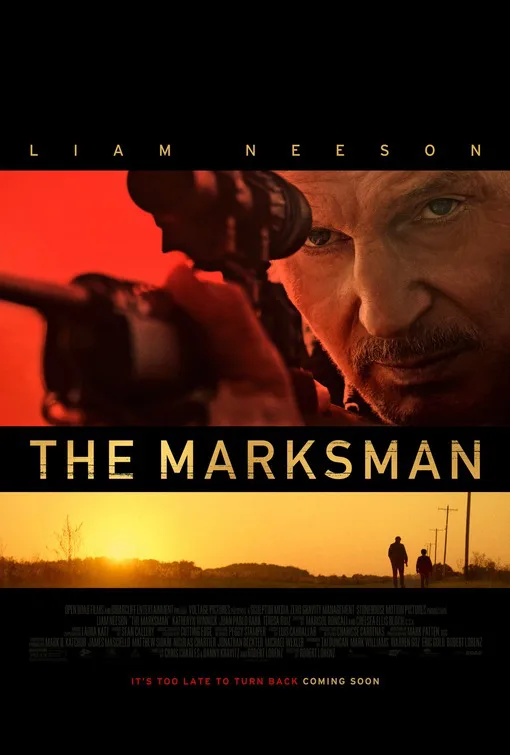

It’s time for your annual Liam Neesoning: that cinematic tradition in which the seasoned star plays a grizzled character with a particular set of skills, which come in handy to dispatch bad guys and rescue good ones. But this year’s entry in the subgenre, “The Marksman,” is particularly mediocre.

There’s not much to the character Neeson plays, or anyone else in the film, for that matter. The story is thin, the suspense is wan, and the action sequences are uninspired. Director Robert Lorenz seems to be aiming for the kind of cranky-old-man-on-a-mission movies Clint Eastwood has directed and stars in of late—which makes sense, given that Lorenz has produced several Eastwood films over the past two decades including “Million Dollar Baby” and “Gran Torino” and directed him in “Trouble With the Curve.” But while the sheen of such movies exists here—perhaps too much, given the subject matter—the substance is sorely missing. And despite his ever-formidable presence, Neeson seems to be going through the motions, even as he’s kicking ass.

Neeson stars as rancher Jim Hanson, a Marine and decorated Vietnam War veteran living a quiet life in southern Arizona along the Mexico border. It’s been a year since his wife died of cancer, and he spends his days with his trusty dog, Jackson, patrolling the property he’s in danger of losing to the bank. At the film’s start, we see him driving along dusty roads in his pickup with his pooch riding shotgun as the setting sun bathes the desert landscape in a warm glow. An American flag waves in the foreground as he approaches his modest house. Cinematographer Mark Patten shoots this patriotic imagery as if it were a commercial for Chevy trucks—all that’s missing is Bob Seger singing “Like a Rock.”

But Jim’s peace is shattered when a mother and son cross into the United States from Mexico through a section of fence that borders his land. They’re on the run from vicious cartel members, and when the mom is shot, Jim agrees to her dying wish that he take care of her tween boy, Miguel (Jacob Perez). Interestingly, Jim takes no political stance on whether they should have entered the country in this manner; ever the pragmatist, he’s more concerned about the prospect of dealing with dead bodies on his property when immigrants succumb to this arduous trek.

The kid is understandably shaken into stunned silence, but a Chicago address scribbled on a strip of paper dictates where Jim must take him to reunite him with his family. Somehow, Jim still speaks no Spanish after years of living along the Mexican border—literally, the extent of his vocabulary is “familia” and “comida”—which seems both unlikely and irresponsible. Instead, he talks to the boy in frustrated, exaggerated English and reluctantly agrees to this journey, thinking that the backpack full of cash the mother gave him could help him pay off his debts.

In contrast with the “Taken” films, this time he’s the one doing the taking, albeit for a good cause. The bulk of “The Marksman” finds Jim, Miguel, and Jackson making their way from Arizona to Illinois, the cartel villains on their tail, led by an especially over-the-top Juan Pablo Raba. Then again, all these characters are flat stereotypes of violent, Mexican thugs; the script from Lorenz, Chris Charles, and Danny Kravitz isn’t interested in exploring them any further. Even Miguel, who’s on screen nearly the entire time, isn’t developed beyond a few simple traits including sweetness, fear and a love of Pop Tarts. (He is thoughtful enough, however, to take Jackson for an early-morning walk while Jim is still sleeping off the whiskey from the night before. But be warned: A later scene involving the dog is the most stressful in the whole movie, and the most unnecessary, given that we’re already fully aware of how dangerous the pursuers are.)

There aren’t many surprises on this journey, and the fact that the old-school Jim proudly carries no cell phone allows for the few hiccups that do occur along the way. (Somehow he manages to pull into a small town in the Texas panhandle and find the gun store on Main Street without the help of Yelp.) Katheryn Winnick has a barely-there supporting role as his stepdaughter, a border patrol agent who shows up every once in a while to track down his whereabouts and try to talk him into turning himself in to authorities. As for the title, Jim doesn’t really get to use his sharpshooting skills until nearly the end, right around the time his gruff demeanor softens, just like we knew it would.