Andy Garcia’s “The Lost City” feels like the distillation of countless conversations and family legends, rehearsed from time immemorial by Cubans who fled their homeland and sought to re-create it in their memories. In every family such stories, repeated endlessly, can become tedious, but there is another sense in which they are a treasured ritual. There was a Cuba, remembered at firsthand only by those who are growing older now, that was a beloved place, and stopped existing when Castro came to power in 1959.

Garcia’s family lived in that older Cuba, and so did Guillermo Cabrera Infante, the Cuban writer and film critic who wrote this screenplay. (The project, long discussed, was not easy for Garcia to finance; Infante died in February 2005.) Infante and Garcia do not deceive themselves that the old Cuba was a paradise: It is seen as corrupt, controlled in key areas by the Mafia, and built on a class system in which many were poor so that a few could be rich. The problem is that Castro did not cure the ills so much as distribute them more evenly, so that more could be miserable. Garcia and Infante are against the old and the new, against both the rotten Batista regime and the disappointment of Castro and Che Guevara. There is a moment in the film when a senator agrees that Batista must be overthrown, but argues wistfully that it must be done “constitutionally.” Fat chance.

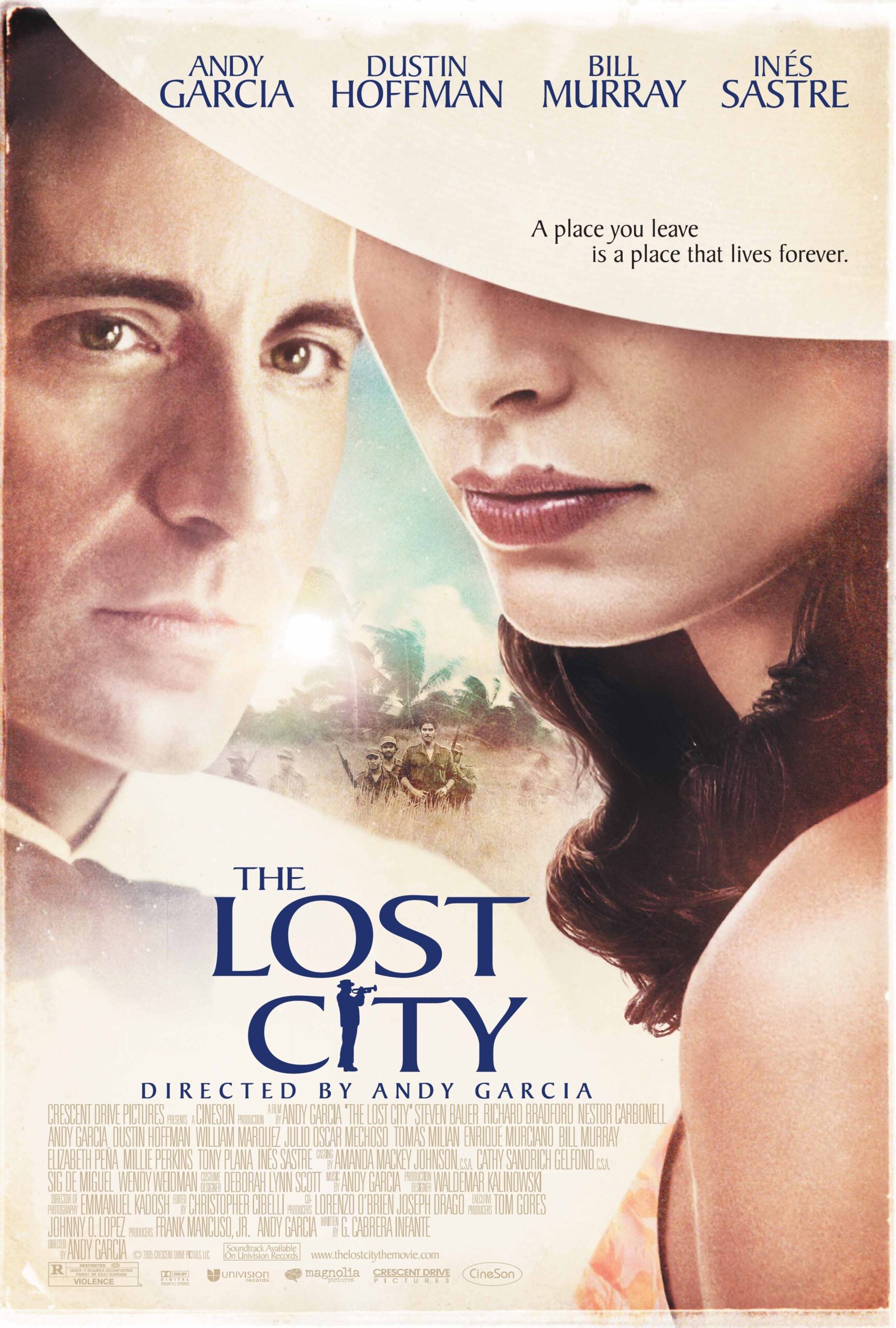

Garcia stars in the film as Fico Fellove, a suave operator who owns and runs a Havana nightclub named El Tropico. Showgirls perform a Vegas-style revue, the customers are elegant and intriguing, and at the door their big sleek American cars glisten in the neon lights. Fico wants this life to continue forever, and like Rick in “Casablanca” he is not particularly political. At a time when Batista’s grip seems to be weakening, when reports from the mountains magnify Castro’s popularity, he receives a visitor: The gangster Meyer Lansky (Dustin Hoffman), who wants to become Fico’s partner in turning El Tropico into a casino. It is the kind of offer Fico can refuse, although that might not be prudent.

Fico’s brothers have a different orientation in the dying days of the old regime. Luis (Nestor Carbonell) embraces the revolutionary cause, and Ricardo (Enrique Murciano) journeys into the mountains to fight with Castro. The rest of the family deplores their decisions; Fico comforts Aurora (Ines Sastre), Luis’ wife, who complains that her husband is away so much he must be cheating. He is not cheating but rebelling, but never mind: Fico ends by falling in love with her himself.

Commenting on all of these events is an enigmatic character named The Writer, played by Bill Murray as a jester who speaks in jokes that contain the truth. His running commentary on Lansky is bold to the point of recklessness. It is never quite explained who The Writer is, although some articles on the film claim he represents the screenwriter, Infante.

If so, he gives Infante an opening into the story that he can use to speak directly, if obliquely, of the absurdity of the times. Indeed Infante himself played such a role under both Batista and Castro, saying what he believed in such a way that no one could be quite certain he had gone too far. Batista nevertheless jailed him, and Castro uneasily made him a cultural attache in Belgium, not then a key posting. A lifelong communist, Infante felt Castro betrayed the party’s principles, and eventually chose exile. His Twentieth Century Job, a collection of his movie reviews, has some of the same wry dubious philosophy expressed by The Writer in the film.

I enjoyed Murray and his scenes, but the character doesn’t fit with the rest of the film. Fico Fellove is not a particularly witty or sunny character and does not suffer fools gladly. Why does he make an exception for The Writer? There are scenes where we almost wonder if The Writer is intended to be physically present at all; for all that Fico takes notice of him, perhaps he is a ghost visible only to us.

The main line of “The Lost City” involves the fall of Batista, Castro’s entry into Havana, the divisions that opens up in the family, and the quick disillusionment with the new regime, which is as arbitrary as the old, and more dogmatic. A musicians’ strike at the nightclub symbolizes the way power is misused by those who have only just possessed it. Fico’s loss is magnified by the heartbreak of the old musician who choreographed the shows and danced as a counterpoint to the girls; he has lost his whole world.

The movie evokes that long-ago world carefully and with a certain poetry; it was shot in the Dominican Republic. There is a lot of music, much of it from the period and performed by the same musicians or their successors. The costumes and the interiors set off the way the characters carry themselves, with grace and confidence.

At 143 minutes, the movie is too long, but it has a lot to cover and a lot to say, and I imagine Garcia has a reason for thinking every scene is necessary. There is romance and some action, but it is not a romance or an adventure film; it is a personal version of what happened in Cuba and what it felt like at the time. Communicating that effectively, it lacks a larger view; newsreel footage covers for historical events that another film might have tried to stage, and the implication is that for characters like Fico, the revolution took place more in the news than in his own life, and he was not quite prepared for such an upheaval. At the end he and a great many others leave Cuba for Miami or New York, where, for Fico, Meyer Lansky awaits.