Soft summer nights, the moon low above the river, “Alice Blue Gown” drifting on the breeze, a rich Southern girl who tastes freedom in Paris and now pretends to desire Memphis society, a poor but honest boy, bitchy debutantes in pastel gowns, wary old ladies in wide-brimmed hats, an opium addict in agony, a good but drunken father, and down by the levee, the ghosts of sharecroppers drowned by a rich man’s dynamite.

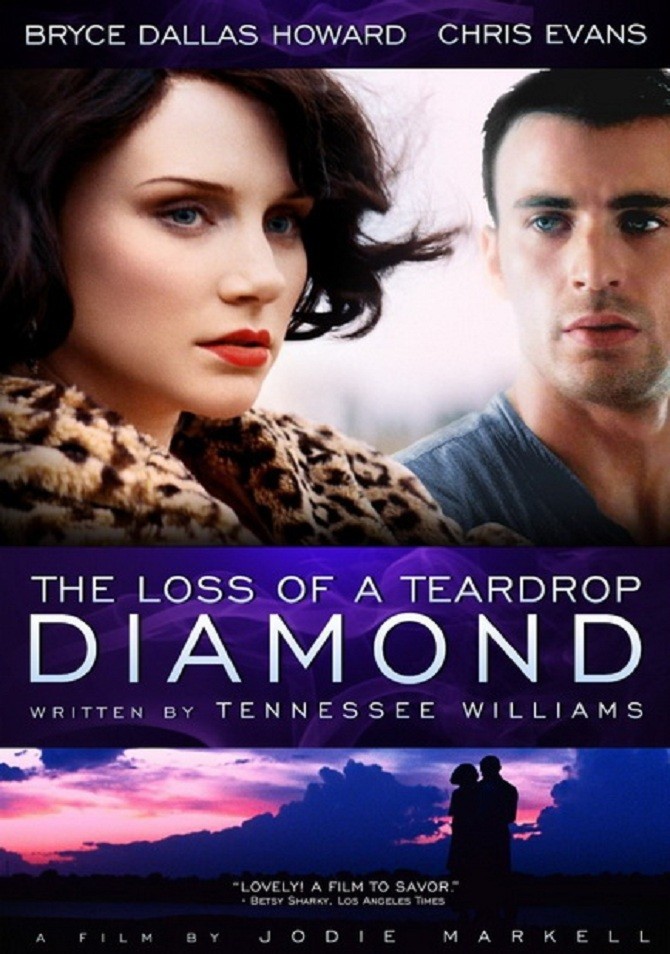

The voice of Tennessee Williams calls to us across the years since his death. It is not strong and fierce, but it is his. “The Loss of a Teardrop Diamond” is an original script he wrote in the ’50s, never produced, long forgotten. It has been filmed in a respectful manner that evokes a touring production of an only moderately successful Broadway play. Understand that, accept it, and the film has its rewards and one performance of great passion.

That would be by Ellen Burstyn, as Miss Addie, who plays it all in her sick bed in a Tennessee country mansion with a debutante party going on downstairs. She has snared Fisher Willow (Bryce Dallas Howard) away from the party and ordered her to lock the doors. Addie lived for many years in Hong Kong, consoled by opium for her lost dreams. She remembers Fisher from a brief visit home. The girl struck her as hard and brave. Now she asks her to do something for her. Give her the pills that will allow her to die.

Fisher is very — agitated — a word Tennessee might have liked. She has hired Jimmy Dobyne (Chris Evans), the good-looking poor boy whose alcoholic father manages her father’s commissary, to be her escort to the party. She even measured him for his evening wear. Jimmy’s grandfather was governor, but the family has fallen back to its knees. Addie senses all has not gone well on their date, discovers Jimmy didn’t want to kiss Fisher when she parked on the riverbank, advises her to escape and go back to Europe.

These are all Williams tropes. The paralyzing stupidity of genteel society. The lure of Europe and the “arts,” and escape itself. The drink, the drugs, the decay. The not-as-young woman hiring a gentleman caller and hoping for the kindness of strangers. Bryce Dallas Howard is affecting as Fisher, but not electrifying, because the material doesn’t have it in it. As Jimmy, Chris Evans is reserved to the point of oddness: a straight arrow without the arrowhead. He may think he’s channeling Paul Newman but he evokes instead the new male lead on a soap opera.

There are extended scenes involving the party downstairs, with everyone perfectly dressed. No one talks unless they have specific dialogue provided. They stand around murmuring like extras. Remember the party scene in Visconti’s “The Leopard,” establishing characters and relationships? This party is as lifeless as the “pageant” staged earlier in a garden by drilled girls for bored old ladies.

And yet I relax and take it for what it is. I feel Tennessee’s yearnings. I saw something of his life indirectly, at a remove. His brother Dakin lived in Chicago and was a frequent player on the newspaper drinking circuit; he announced his candidacy for governor at a press conference at Riccardo’s. He had a platform, but the only plank you ever heard about was that he was the brother of Tennessee — and of Rose, you remember, the sister. He was a friendly man, courteous, sharing I suspect the joke of his several runs for office. He was the comedy, Rose was the tragedy, and Tennessee was the recording angel.

You will want to see this film if Tennessee means anything to you. Does he, to most people, anymore? And do Albee and Miller? A non-musical play can hardly open on Broadway these days. But this is a Tennessee Williams screenplay. And in it, one of the great Williams women, Miss Addie, and one of the great Williams actresses, Ellen Burstyn. That ought got mean something. Well, shouldn’t it?