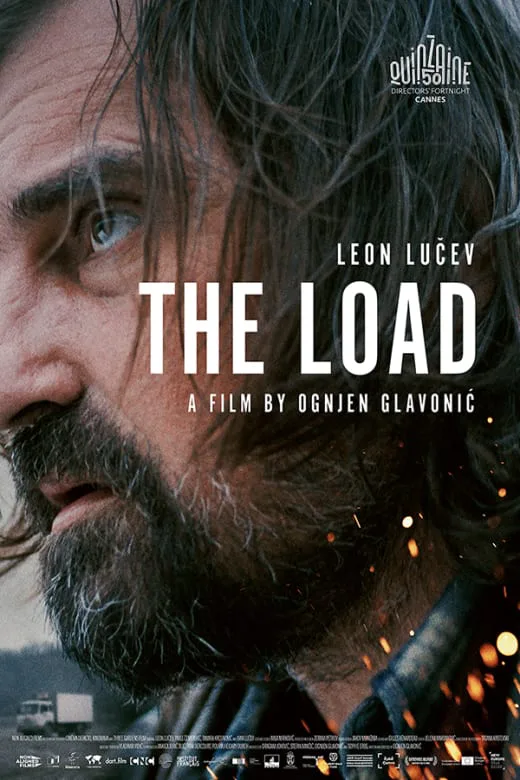

It’s in the midst of a tense phone call that the dog first catches our eye. A truck driver, Vlada (Leon Lučev), has been tasked with transporting an unidentified shipment from Kosovo to Belgrade during the NATO bombings of 1999. No information is granted to Vlada about the contents he’s carrying, but with his factory job axed and his country thrust into chaos, this gig promises a secure source of income. As he speaks on the phone with his wife (Tamara Krcunović) about some impending medical test results, a stray dog materializes outside the window, racing between the buildings before disappearing around a corner. In an intriguing move, the camera chooses to track the canine’s whereabouts, inviting us to hone in on details that might otherwise be overlooked. When Vlada steps outside, he encounters the dog and finds a sucker embedded in its fur, the remnant of its owner who appears to have vanished, like many residents in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

This pre-title sequence in Serbian filmmaker Ognjen Glavonić’s mesmerizing narrative feature debut, “The Load,” prepares us for how the background will function throughout the picture, upping the suspense with imagery glimpsed solely in side mirrors or through the dense branches of trees. Since the premise directly evokes Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 nerve-shredding classic, “The Wages of Fear,” we find ourselves flinching along with Vlada every time we hear a suspicious noise emanating from his truck. Like Clouzot’s doomed protagonists, is he transporting nitroglycerine that could blow his vehicle into smithereens if it hits a pothole? Though Glavonić keeps the shipment a mystery for as long as possible, there are many indications early on that his film doesn’t aspire to be a remake a la William Friedkin’s 1977 “Sorcerer.” Just as a blocked bridge forces Vlada to reroute his journey, the narrative consistently veers off into unexpected territory, and the more it frustrates our expectations, the more it has us hooked. This is a film hinging not on cathartic explosions but rather, the gradual discovery of horrifying, self-implicating secrets.

Tatjana Krstevski’s deep-focus photography casts its ominous spell from the very opening shot, as a van carrying Vlada and his fellow drivers glides along an inky black hillside as the fire of warfare sets the sky ablaze just beyond the horizon. There are no onscreen casualties in “The Load,” and yet every frame reeks of death, not just in the sense of fallen civilians, but in the decay of a culture that has become the very thing it once fought against. Adding to the pervasive unease is the lack of a score, lending each scene a post-apocalyptic aura in line with Hitchcock’s “The Birds” (whenever songs do emerge, they fulfill the role of a Greek chorus). Little by little, we learn more about our central character as he warms up to Paja (Pavle Čemerikić), a young stowaway who reminds the driver of his own teenage offspring, Ivan (played by Lučev’s actual son, Ivan). Turns out the fathers of both Vlada and Paja fought in the Yugoslav Army, the history of which haunts various pit stops that they encounter, particularly the towering WWII monument where two young pickpockets hide within its vast circular orifices. This sequence is among a handful of occasions where Glanović boldly breaks from his primary plot line and allows us to linger in the lives of those existing on its periphery. We follow the thief only after Vlada charges after him, thinking he’s Paja—who we eventually see, in a deftly subtle reveal, urinating in the distance.

After outwitting Vlada, the kid shares with his pal what he took from the truck: its stash of cigarettes along with a decades-old lighter commemorating the fifteenth anniversary of a landmark battle in the Yugoslav Partisan War. The personal significance of the lighter and its sudden absence isn’t indicated until a chilling monologue delivered by Vlada to Ivan in the film’s closing moments, as the camera pans up to a tree. It’s only after reflecting on the tree that we realize how it simultaneously serves as a key symbol in the war story, an illustration of the film’s plot structure as it branches off into various directions and an apt metaphor for the underlying conspiracy reverberating beneath the surface of Glanović’s narrative, tying back to the final shot of his 2016 documentary, “Depth Two.” Juxtaposing audio testimonials with Krstevski’s footage of the locations where the recounted events once occurred, Glanović’s previous feature dealt frankly with the crimes committed by Serbian president Slobodan Milošević, whose bust Vlada stumbles upon in the shadows of a police compound. Milošević’s genocidal “cleansing,” a term directly evocative of Hitler, required the involvement of the military, police and numerous citizens to aid in the burying of its evidence, an atrocity the filmmaker believes his country still has yet to adequately address.

Caught within the branches of the tree are balloons reminiscent of those released into the sky much earlier by the hostile celebrants at a wedding reception, one of many instances in which the film circles back on itself. Circular shapes are among the film’s most striking visual motifs, emerging in the form of not only the sucker and war monument, but a marble Vlada finds upon cleaning the truck, and the flaming graffiti created by a group of kids outside the wedding, after one of them swipes body spray gifted for the newlyweds. All three of the film’s disconnected story threads concerning youth rhyme in provocative ways, with the first two linked by theft. Whereas the youngest of the kids stumble upon a relic of their ancestor’s past, their somewhat older peers relish an act of anarchy mirrored by the burned residue of NATO fliers later arranged by Ivan, a budding young man, and his pals to resemble the shape of a penis, thus satirizing the phallic symbols of patriarchal nationalism. It seems hardly a coincidence that Ivan’s name is one letter removed from that of the titular subject in Glavonić’s first feature doc, 2014’s “Zivan Makes a Punk Festival,” whose determination to provide a platform for vital work inspired the director to found a film festival in his hometown of Pančevo. His choice to have Vlada live in Pančevo is a pointed one, demonstrating how those who enabled forces of evil and subsequently chose to live in denial of them exist in all corners of Serbia, and the world as a whole.

Viewers unschooled in Milošević’s reign of terror likely won’t pick up on these historical nuances during their initial viewing of “The Load,” and that is by design. Keeping us in the dark along with Vlada about his enigmatic plight allows its timely themes to resonate on a level that is poetic, intuitive and utterly universal. While his father’s generation fought against fascism, Vlada has found history cycling backward—only this time, it’s his country submitting to and covering up the inhuman orders of a tyrant. His story may have taken place two decades ago, but it’s also occurring at this exact moment in every country run by chauvinists who prioritize their own self-interests above all else, including the future of their species. The estimated 500 civilian deaths that reportedly occurred as a result of the 1999 NATO bombings were never investigated by international courts, affirming that the blood spilled during this period is on American hands as well. Paja and Ivan’s shared desire to form a band represents the urgent need of Glavonić’s generation to learn from the past by unearthing truths their parents had kept concealed deep beneath the ground. This is one of the year’s best films.