If “The Lighthorsemen” had been an American film, it would have been shot 40 years ago and directed by John Ford, and it would have starred Henry Fonda, James Stewart or John Wayne. It has the same kind of feeling and energy as Ford’s historical Westerns, which glorified the U.S. Cavalry in thundering horse charges, and then cut to Army politics back at Fort Apache. But “The Lighthorsemen” is an Australian film, sort of a companion piece to “Gallipoli,” and equally proud and chauvinistic.

It takes place during World War I, in the deserts of the Middle East, where an Australian light horse detachment, 800 strong, was stationed to join British troops on the front against Germans and Turks. The story is quickly summarized: Everything depends on the capture of Beersheba, which is held by the enemy along with its precious wells of fresh water. And the lighthorsemen do, of course, capture Beersheba.

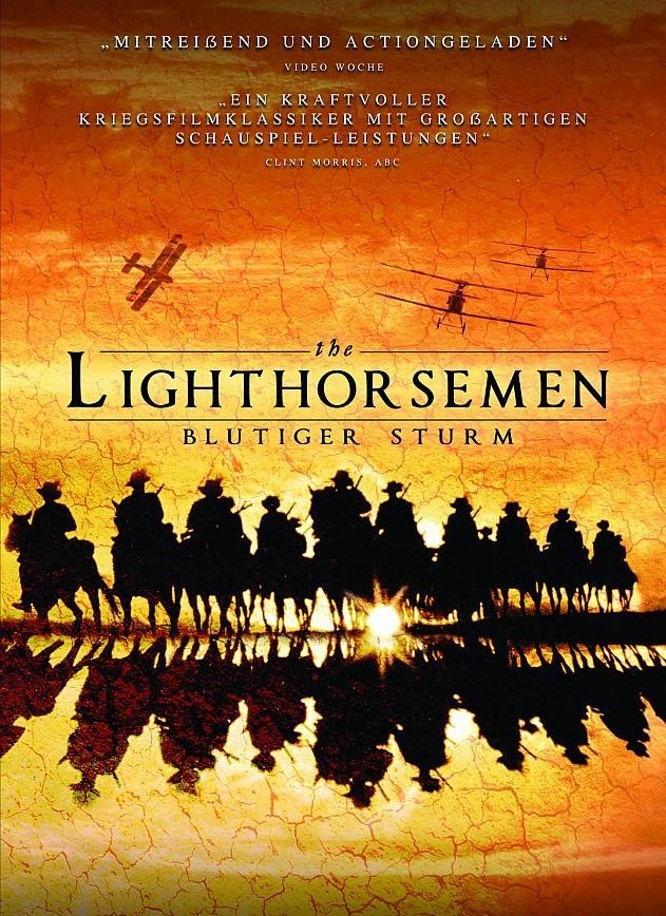

That’s the story. The rest of the movie is atmosphere, action and horses – lots of horses, wonderful horses, good-looking, high-spirited horses who star, finally, in one of the most thrilling cavalry charges ever filmed. The horses are so photogenic that the human actors hardly have a chance against them, especially considering that all of their dialogue has been heard countless times before in countless earlier movies, some of them no doubt actually directed by Ford.

We meet a four-man regiment of Australian lighthorsemen (following one of them, of course, all the way from the day he enlists as a greenhorn kid from the outback), and we get to know them, although not very well, because this movie is not a psychological drama. We witness several standard scenes, which include the usual military briefings, inspections of maps and moments when generals look at the horizon with field glasses. And we get the obligatory scenes in which characters explain the situation to each other, so that we can understand it, too. The only time this worked was when an elderly general (Bill Ware) explained why he wanted to take Beersheba, and how.

Unfortunately, despite all of the other briefings and countless subtitles identying various general’s headquarters, I was disoriented almost all the way through the movie. The only really lucid battle scene was the last one, in which Beersheba was over there and the lighthorsemen were over here, and then they attacked. It’s easy to ridicule old U.S. Cavalry potboilers, but at least they were simpleminded and dogged enough in their storytelling that you always knew what was happening. “The Lighthorsemen” could actually use a few more cliches; as it is, the only one we get is the obligatory scene where the young soldier is wounded and evacuated to a field hospital, where he falls in love with the nurse.

The film’s final cavalry charge redeems a lot, however. It comes as the German and Turkish commanders squabble over plans to blow up the water wells to keep them out of Allied hands. And it is a humdinger, a daring, flat-out, no-holds-barred charge across the desert and under the range of of the enemy cannon. I haven’t seen a better action scene with horses since “Ben Hur.” Whether it’s worth the price of admission depends, of course, on how much you like horses.