It’s said that European films are about adults, Hollywood films about adolescents. For evidence, compare two recent films: “The Legend of Rita” and “Invisible Circus.” Both are about young women who become involved with German terrorist gangs. The German film is told through the eyes of a woman who tries to remain true to her principles while her world crumbles around her. The American film is told through the eyes of a kid sister, who seeks the truth of her older sister’s death and ends up sleeping with her boyfriend, etc. The German woman is motivated by political beliefs. The American woman is motivated by family sentiment, lust and misguided idealism, in keeping with Hollywood’s belief that women are driven more by sex than ideas, and that radicalism is a character flaw.

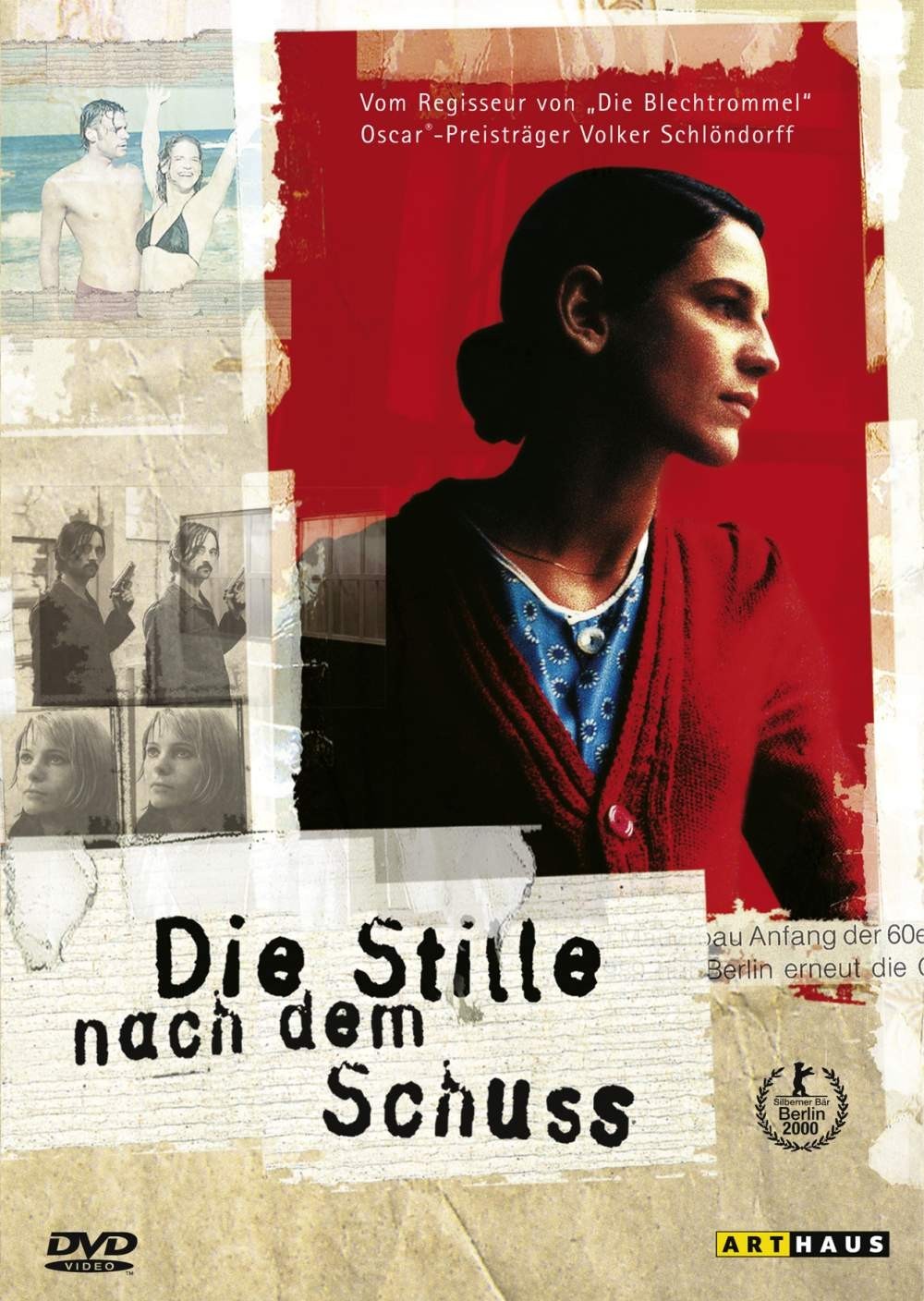

“The Legend of Rita,” directed by the gifted German Volker Schlondorff (“The Tin Drum“), won two acting prizes and the award as best European film at the 2000 Berlin Film Festival. It stars Bibiana Beglau as Rita, a West German who belongs to a left-wing terrorist group in the 1970s. The group robs banks, kills people and inspires a dragnet after a jailbreak. The movie doesn’t make it easy for us: Rita is not an innocent bystander and kills a policeman herself. But this isn’t a simplistic parable about her guilt or motivation; it’s about the collapse of belief during the last decade of the Cold War. Schlondorff believes his audience may be grown up enough to accept a story about a woman who is not a heroine. Imagine that.

The setup comes as Rita, who has been in Lebanon, attempts to enter East Germany with a revolver in her luggage. She is questioned by Hull (Martin Wuttke), an agent for Stasi, the East German secret police, and allowed to enter the country with the weapon but without her bullets. Later, because Hull (and Stasi, it is implied) sympathizes with her group’s opposition to capitalism, she is offered a new identity.

Cutting her ties with her name, her past and everyone she knows, Rita becomes a cog of the working class. This all right with her: She isn’t a naive hobbyist but seriously believes in socialism. With a new name and identity, she goes to work in a textile factory and becomes friendly with a fellow worker named Tatjana (Nadja Uhl); their affection nudges toward a love affair, but when her identity is discovered, Hull yanks her into another life, this time running a summer camp for the children of factory workers. Here she falls in love with a man. But can she marry a man who doesn’t know who she really is? The movie isn’t about love, unrequited or not. It’s about believing in a cause after the cause abandons you. Here the intriguing figure is Hull, who is not the evil East German spy of countless other movies, but a bureaucrat with ideals, who likes Rita and believes he is doing the right thing by protecting her. When the Berlin Wall collapses, there is an astonishing exchange between Hull and the general who is his superior. The general says West Germany demands the extradition of Rita and other terrorists.

“How did they know they were here?” asks Hull.

“They always knew,” says the general.

“How did they find out?” “From us, perhaps.” “The Legend of Rita” shows a lot of everyday East Germans, workers and bureaucrats, who seem unanimously disenchanted by the people’s paradise. Rita’s original cover story was that she moved to the East from Paris because of her ideals; not a single East German can believe that anyone from the West would voluntarily move to their country. In the last days of the East, as the wall is coming down, Rita makes a touching little speech in the factory cafeteria, saying the ideals of socialism were good, even if they were corrupted in practice. The East German workers look at her as if she’s crazy.

“The Legend of Rita” doesn’t adopt a simplistic political view. It’s not propaganda for either side, but the story of how the division and reunification of Germany swept individual lives away indifferently in its tide. In 1975, Schlondorff and his wife, Margarethe von Trotta, made another strong film, “The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum,” set in West Germany. It was about an innocent bystander caught in the aftermath of raids by the Baader-Meinhof Gang, the same group Rita presumably belongs to. From West or East, from right or left, his stories have the same message: When the state’s interests are at stake, individual rights and beliefs are irrelevant.