Adam Brooks’ “Invisible Circus” finds the solution to searing personal questions through a tricky flashback structure. There are two stories here, involving an older sister’s disappearance and a younger sister’s quest, and either one would be better told as a straightforward narrative. When flashbacks tease us with bits of information, it has to be done well, or we feel toyed with. Here the mystery is solved by stomping in thick-soled narrative boots through the squishy marsh of contrivance.

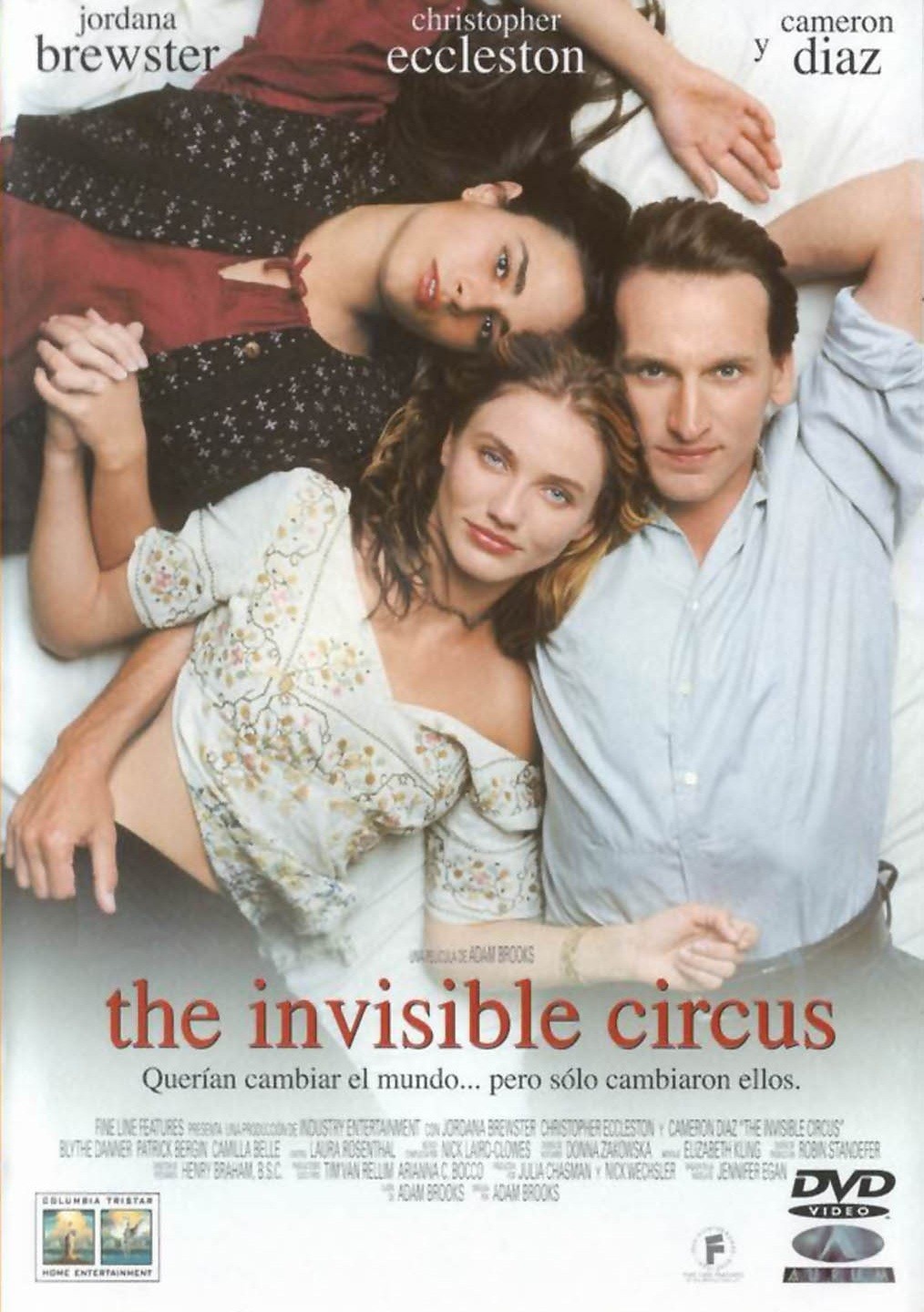

Jordana Brewster stars as Phoebe, 18 years old in 1976. In the summer of 1969, she tells us in her narration, her sister Faith went to Europe and never came back. The story was that Faith (Cameron Diaz) killed herself in Portugal. Phoebe doesn’t buy it. After a heart-to-heart with her mother (Blythe Danner), Phoebe sets off on a quest to solve the mystery, message, meaning, method, etc., of Faith’s disappearance.

The search begins with Wolf (Christopher Eccleston), Faith’s old boyfriend, now engaged and living in Paris. Since Wolf knows all the answers and that’s pretty clear to us (if not to Phoebe), he is required to be oblique to a tiresome degree. And there is another problem. In any movie where a lithesome 18-year-old confronts her older sister’s lover, there is the inescapable possibility that she will sleep with him. This danger, which increases alarmingly when the character is named Wolf, is to be avoided, since the resulting sex scene will usually play as gratuitous, introducing problems the screenplay is not really interested in exploring.

I cringe when a man and a woman pretend to be on a disinterested quest, and their unspoken sexual agenda makes everything they say sound coy.

Wolf and Faith, we learn, were involved in radical 1960s politics. Faith was driven by the death of her father, who died of leukemia caused by giant corporations (the science is a little murky here). Phoebe feels her dad always liked Faith more than herself. What was Dad’s reason? My theory: Filial tension is required to motivate the younger sister’s quest, so he was just helping out.

The movie follows Faith, sometimes with Wolf, sometimes without, as she joins the radical Red Army, becomes an anarchist, is allowed to help out on protest raids, fails one test, passes another and grows guilt-ridden when one demonstration has an unexpected result. Phoebe traces Faith’s activities during an odyssey/travelogue through Paris, Berlin and Portugal, until we arrive at the very parapet Faith jumped or fell from, and all is revealed.

I can understand the purpose of the film, and even sense the depth of feeling in the underlying story, based on a novel by Jennifer Egan. But the clunky flashback structure grinds along, doling out bits of information, and it doesn’t help that Wolf, as played by Eccleston, is less interested in truth than in Phoebe. He is a rat, which would be all right, if he were a charming one.

There is a better movie about a young woman who drops out of sight of those who love her and commits to radical politics. That movie is “Waking The Dead” (2000). It has its problems, too, but at least it is unclouded by extraneous sex and doesn’t have a character who withholds information simply for the convenience of the screenplay. And its Jennifer Connelly is much more persuasive than Cameron Diaz as a young woman who becomes a radical; she enters a kind of solemn holy trance, unlike Diaz, who seems more like a political tourist.