Henry Lawson’s 1892 short story The Drover’s Wife is a core Australian text, the tale of a woman living in a remote rural cabin in the outback of the late 19th century. Her husband is away for months at a time, driving livestock, and when a snake approaches her cabin, she protects her children. For generations, it exemplified the resilience and determination of the white settlers.

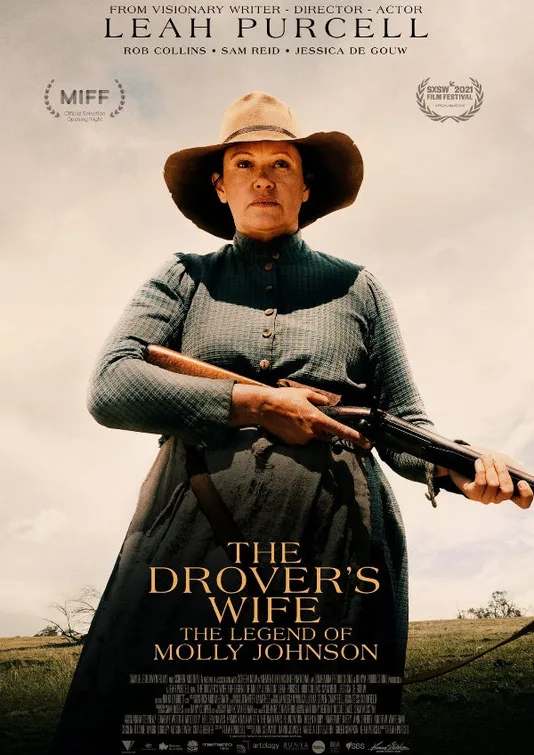

But Lawson’s story never told us the woman’s name. She is identified only by her relationship to her husband and her children—and the snake. Now, with “The Legend of Molly Johnson,” Leah Purcell has remixed the story, giving the central character a name, a history, and an inner life. Purcell first re-wrote the story as a novel and a play, and now she has written, directed, and starred in a film. Purcell does not just tell us the woman’s name is Molly; she show us that the story deserves to be claimed as a legend. She highlights the agency Molly wrests from a system that does its best to hold on to all the power.

The use of the word “legend” in the title and the Western-style setting in the Australian outback show the influence of classics like “Fort Apache,” “Rio Bravo,” and “The Searchers.” Like those films, there is a mythic tone to the story of the struggle of untamed settlers in an untamed wilderness. We hear a British military officer who is assigned to bring order to the area cautioned by his wife: “Whilst hunting savages in this land, please do not turn into one.” As that suggests, this film engages more critically with issues of masculinity, colonialism, injustice, and abuse than its mid-century predecessors. The military officer’s wife, a crisp but sympathetic Jessica De Gouw as Louisa Klintoff, is the closest we have to a representative of the filmmaker’s view and, she hopes, of ours. Skillfully weaving in themes of race, gender, abuse, and historic injustice while making each character authentically human, the film calls on us to consider the human strength and the human cost of history.

Molly lives in a remote cabin with her children. Her husband is gone for months at a time as a “drover,” moving livestock from one area to another. Purcell wisely lets close-ups of her own face convey more than any action or dialogue could about who Molly is, what matters most to her, and what made her the person whose expression shows the struggle between constant worry and resolute determination. We first see Molly aiming her gun at an intruder, as she does repeatedly throughout the story. She has reason to suspect that anyone coming near her property means to take something from her and her children. Her only option is to aim first and fast. “I will shoot you where you stand and bury you where you fall,” she threatens one trespasser.

In that first encounter, though, it is she who takes. A bull has wandered their way. She shoots it between the eyes with no hesitation to make dinner for her children. The next to come by, enticed by the aroma of the beef, are the Klintoffs, Louisa and her husband, Nate (Sam Reid), just arrived from London and a bit dazed by the vastness of Australia. They persuade Molly that they mean no harm and she allows them to stay. As they talk, she decides to entrust them with taking her children to town to get provisions. And there is another reason; she is about to give birth, and it is best for them not to be there.

Another intruder arrives as she goes into labor. He is Yadaka (Rob Collins), indigenous and an escaped prisoner. But she is vulnerable and he offers help. She puts down her shotgun. The baby girl does not survive, and he offers to make the coffin and dig the grave. In a film filled with beautifully framed and striking images, one of the most powerful is the baby’s grave. It lies next to two others, a child and a parent, both with crude crosses. The new one marked only with the name “Mary” painted on a rock.

Yadaka stays on to help and his scenes talking to Molly’s oldest son, Danny (Malachi Dower-Roberts) about manhood are among the film’s best. In the town, Nate struggles to impose British law in an environment that does not have the traditions and cultures that underly those laws. Louisa, who wants to write about her experiences and observations there, becomes ill. Conflicts arise in the town and some of them reach Molly’s cabin. She is implacable and resolute, but when her children are threatened, we see how fragile her situation is, and what kind of sacrifice she is willing to make.

The cinematic storytelling in this film would be exceptional by any director, and credit has to go to Director of Photography Mark Wareham and editor Dany Cooper. But it is remarkable that Purcell, who has already told this story as a novel and a play, was willing to jettison word-based storytelling to make this version rely so effectively on the visuals to communicate the emotions and details. Like John Ford and Howard Hawks, she understands the power of the landscape in framing the challenges of individuals struggling with the harsh environment, physical and cultural. Purcell has taken Lawson’s character and given her a name, a history, and a story worthy of the word “legend.”

Now playing in select theaters and available on digital platforms.