Like “Danny Deckchair,” “The Last Shot” is inspired by a real story that provides the inspiration for otherwise unbelievable events. Yes, the FBI really did once produce a phony movie as a sting operation. And yes, the filmmakers had no idea their producer was an undercover agent. Directors get screwed all the time by phony money men, but this was one time they couldn’t go to the FBI.

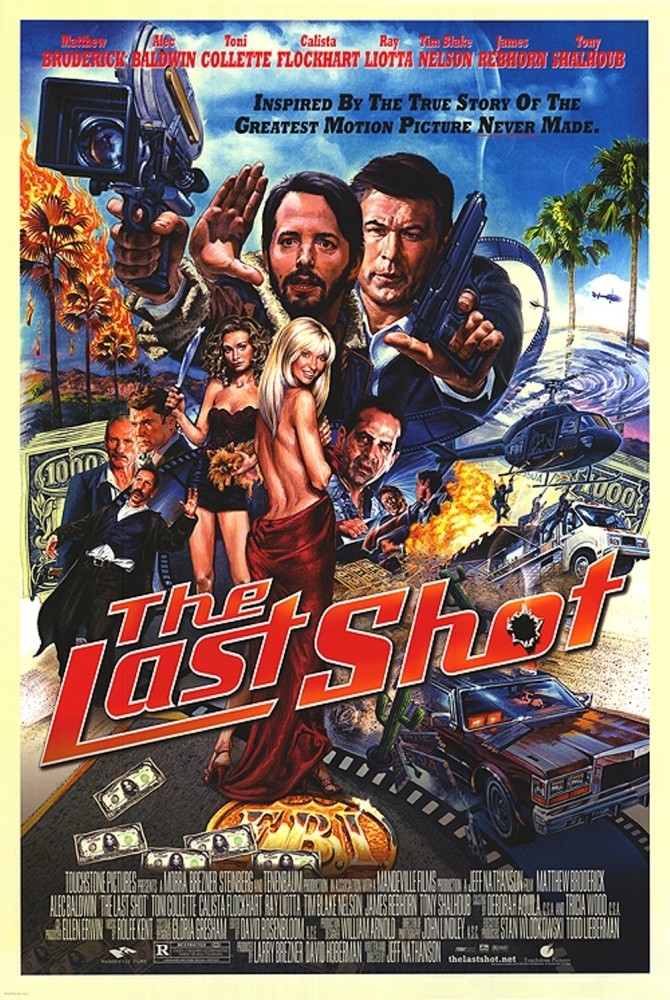

The movie stars Matthew Broderick and Alec Baldwin as two men who desperately want to escape dead-end jobs. Broderick plays Steven Schats, an usher at Mann’s Chinese Theater, who like almost everyone with even the most tenuous connection to the movie industry, has a screenplay he’d like to make into a movie. Baldwin plays Joe Devine, an FBI agent trapped in a low-level job in Rhode Island, and hungry to move up. When he learns that mob-connected firms are muscling in on show-biz jobs in Providence, he has a brainstorm: He will set a trap by producing a movie that will tempt mobsters into incriminating themselves.

But first he needs a screenplay, probably from a would-be filmmaker so naive he could be deceived by Devine’s lack of credentials and, for that matter, his blissful ignorance of the movie business. Steven Schats is his pigeon. With the innocent enthusiasm which Broderick specializes in, the usher pitches a screenplay set in Arizona, about a tragic heroine who staggers out of the desert and into a series of murky flashbacks.

Devine green-lights “Arizona,” but has one stipulation: The movie has to be shot in Providence. Schats is thunderstruck: How can he shoot a location Western in Rhode Island? Devine says it’s necessary for “production reasons,” and talks about backdrops, special effects and fake cacti. Schats needs a Hopi Indian cave for a sacred ceremony. Devine suggests a storage locker.

“The Last Shot” is not a well-oiled enterprise but more of a series of laughs separated by waits for more laughs. It has a kind of earnest, eager quality, and it’s so screwy you feel affection for it; it creates completely gratuitous characters like the production executive played by an unbilled Joan Cusack, who barks into her intercom, “Bring me my back brace and my banjo!” There is no reason for the Cusack character except that she is relentlessly hilarious.

The screenplay, by the director Jeff Nathanson, has a nice line in funny free-standing dialogue. My favorite is probably, “Your dog is dead. She killed herself.” I also like Tony Shaloub, as a gangster, saying “I see you noticed my face. My wife set me on fire. Six months later, our marriage fell apart.” And Devine boasting to Schats, “My wife did the hair on ‘Jaws’.” She must have been very young at the time, but never mind. I also liked the moment when Schats talks about “the business” and Devine thinks he means prostitution. A mistake anyone could make.

Toni Collette is funny as a ditzy would-be sex bomb who desperately needs the lead and desperately plays it, staggering out of the Rhode Island desert on cue and stabbing herself in the leg to generate a Method “sense memory” of anguish. Familiar actors like Tim Blake Nelson, Buck Henry and Ray Liotta work their supporting roles for everything they can get out of them.

I had the sense that one more trip through the word processor might have done the screenplay some good, but at the same time I enjoyed “The Last Shot” almost unreasonably, considering its rough edges. If a comedy makes you laugh, you can forgive its imperfections. What is seductive about this one is the way Joe Devine begins to think of himself as a real movie producer, and gets caught up in the struggle to bring “Arizona” to the screen. What the movie gets right is the way even the most hopeless production can engender love and loyalty from its cast and crew, who talk themselves into believing it could be great. Nobody ever sets out to make a bad movie, and that’s the lesson Joe Devine learns in spite of himself.