Even before the opening credits, I learned a terrifying new term in “The Last Sermon”—”organic shrapnel.” Director Jack Baxter points to a place on his arm where pieces of a suicide bomber’s body are still embedded. As he anxiously waits to meet the brother of one of the terrorists, we go back in time to the attack.

In 2003, Baxter was filming a documentary about Mike’s Place in Tel Aviv, a blues bar he saw as an oasis of music that transcended cultural and religious divisions, when two terrorists arrived. A waitress and two musicians were killed and 50 people were injured, including Baxter and the security guard who kept the bombers from entering the bar. That story became Baxter’s documentary, “Blues by the Beach.”

In this film, he continues to explore the people and issues behind the attack, from his own very personal efforts to meet the family of the bomber to geopolitical issues: immigration, refugees, extremism. The link between the forest and trees perspectives is uncertain and often awkward. The film introduces us to some intriguing characters, several of whom deserve their own movies, but it would benefit from a clearer focus.

The title of “The Last Sermon” comes from the Prophet Mohammed’s call for unity in his final words to his followers: “All mankind is from Adam and Eve, an Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab; also a white has no superiority over a black nor a black has any superiority over a white—except by piety and good action.”

Baxter wants to bring those words to people, through this film and very directly in one scene where he borrows a stepladder at London’s legendary Speaker’s Corner and starts to preach. As we see briefly earlier in the documentary, this is not the first time he has brought the words of prophets to a sidewalk pulpit. “I was a Jesus freak for seven years,” he tells us, including street proselytizing and fasting two days a week. “We would die for God,” he says, very aware of the parallels to the suicide bomber who is literally under his skin. The fervor within that led and kept him there and the skepticism that led him away are both reflected in his fascination with beliefs, those that bring us together and those that keep us apart. The film’s American-Israeli producer Joshua Faudem brings his own experiences as a former soldier in the Israeli army who worked at security checkpoints, who says it makes him sick now to remember their treatment of Muslims.

Baxter and Faudem travel around Europe to try to understand the forces promoting and fighting against terrorism. They meet with a benevolent Muslim religious leader in Serbia who dreams of a borderless world. He courteously asks if Faudem would like kosher food and gently chides him when he says he does not keep kosher. The Imam delights in Baxter’s New York accent, but thinks he sounds like Clint Eastwood, a comment in itself on cultural borderlessness. They visit a Berlin-based charity supporting refugees with “Trump-free Zone” signs, and a Hungarian official who points proudly to the electrified fence he had constructed to keep out refugees, explaining that he will welcome those from neighboring countries (i.e., white and Christian) but not Muslims. He says, “Hungarian culture is not comfortable with Islam” and “If I want to get some experience with Islam I can travel to Saudi Arabia.” I was especially taken with a musician named Aeham Ahmad, a refugee in Germany, who also carries shrapnel in his body. “I know Beethoven and I know Islam,” he says. He brings his own kind of preaching to the street, taking his piano into the local neighborhoods. When Baxter offers him a possible gig in the US, he cheerfully responds with a laugh, “Would Mr. Trump allow me?”

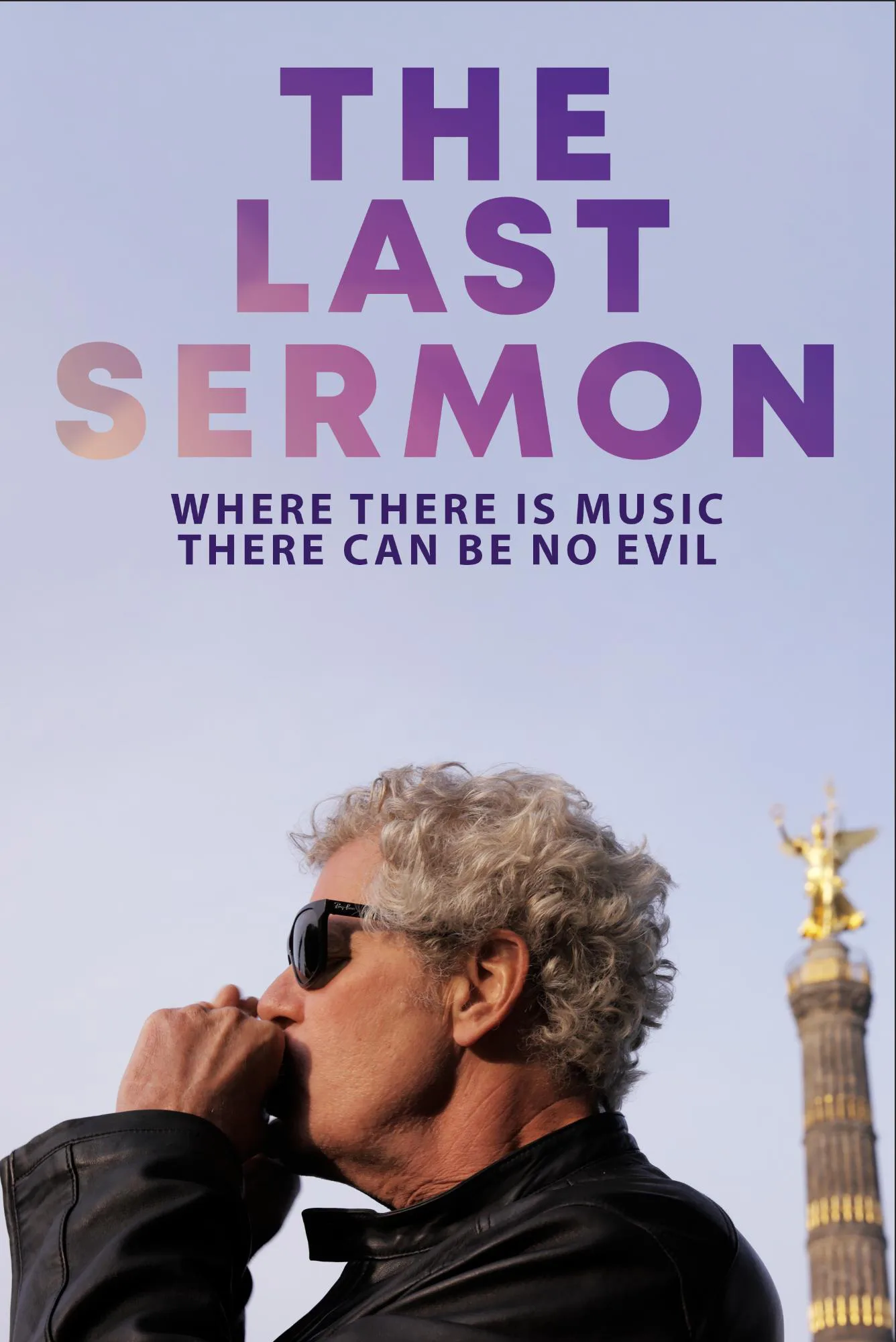

We see a graffiti artist who creates a mural with “peace be upon you” in exquisite Arabic calligraphy, a Parisian “radicalization consultant” (actually a more of a de-radicalization counselor), a Serbian refugee fashion designer who wears a hijab, and Olivie Žižková, a Czech actress, singer, and political candidate who represents an “attractive figure to represent the anti-refugee voices.” We hear one of her songs, the catchy, up-tempo melody making the casually hateful lyrics even more chilling, in sharp contrast to the quote at the beginning of the film that “where there is music there can be no evil.” But the man quoted is known more for aspiration than reality, so much so that his very name has become an adjective for a fanciful vision of a better world: Don Quixote.

Baxter travels in time, too, as we all do. The world goes on while he is making the movie, and more terrorist attacks occur, including one at a London train station and one at an Ariana Grande concert in Manchester. Perhaps it is the overwhelming impact of these events that shrink the movie’s scope down to the very personal moments where he finally, surprisingly loses his temper with a mild-mannered community leader, and when he sobs, concluding that “I don’t really want to know what we wanted to know.” Perhaps he feels that his quest has been Quixotic.