In watching a documentary that depends almost entirely on the testimony and self-presentation of its central subject, individual viewers ultimately have to decide whether or not they believe that person, or to what extent they believe him. In “The Last of the Unjust,” French documentarian Claude Lanzmann’s nearly four-hour addendum to his monumental Holocaust chronicle “Shoah,” the subject is Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein, the only survivor from a group of Jewish “Elders” who, in effect, helped the Nazis run some of their concentration camps and after the war were accused of collaboration.

My hunch is that most viewers, whatever their previous views on this fraught subject, will come away not only fascinated but largely convinced by Murmelstein, who comes across as extremely intelligent, self-aware, sincere and honest, and whose explanations of his actions at the Czech “show” camp Theresienstadt seem eminently sensible and defensible, even as they offer a window into a strange corner of the Nazi horror. If that view prevails, Lanzmann will have performed another great service of revisionist clarification to those concerned with Holocaust.

Although he later decided the footage didn’t fit “Shoah” and only recently fashioned it into a stand-alone film, Lanzmann interviewed Murmelstein in 1975 at his home in Rome. One of the bitter ironies of his story is that though Murmelstein loved Israel, he never visited there because of the suspicions visited on him and other camp elders, even though he might have helped considerably in the prosecution of Adolf Eichmann.

Indeed, it’s likely that no Jew ever had a closer view of Eichmann than Murmelstein, who, as a rabbi in Vienna in 1938, worked under the Nazi leader—and instructed him in Jewish culture—while managing to save 120,000 Jews by getting them out of the country. Repudiating Hannah Arendt, whose reporting of Eichmann’s post-war trial in Israel was so defamatory to wartime Jewish Elders like himself, he says the German commander was no embodiment of “the banality of evil” but rather a uniquely evil, sadistic and anti-Semitic “demon.”

The core of Murmelstein’s story, though, takes place at Theresienstadt, where he was the last of three Jewish Elders (his two predecessors were each killed by the Nazis with a bullet to the head) whose role was to organize the camp life of the Jews. To refuse the job would mean an instant death sentence, but Murmelstein clearly saw it as a opportunity to help his fellow inmates in ways large and small. No doubt the position was hugely uncomfortable—he describes it as being “between the hammer and the anvil”—but it’s easy to believe that, as a self-described “big mouth” who’d learned how to handle Eichmann, he was no pliant flunky for his evil overlords.

Thereseinstadt, in any case, had no gas chambers (indeed, he says its residents didn’t know what was going on at places like Birkenau and Auschwitz until they were sent there themselves, as many eventually were). Rather, as “Hitler’s gift to the Jews,” it was set up and maintained as a model ghetto where rare outside visitors like Red Cross representatives could be shown a healthy and safe Jewish population. When outsiders weren’t looking, of course, the conditions for the residents were unspeakably barbaric, full of the hardships, humiliations and terrors that were the Nazis’ special genius.

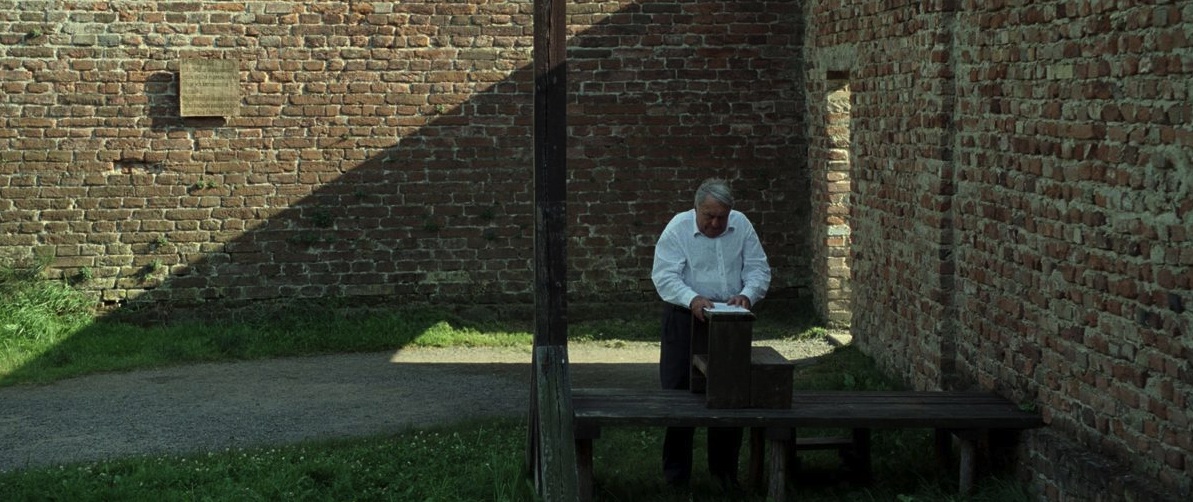

While relaying Murmelstein’s detailed and absorbing account of life in Thereinstradt, Lanzmann employs two sets of illuminating, and indeed quite amazing, visual aids. One is a group of drawings of the camp’s daily life—including carts hauling corpses and wraith-like humans straggling along the streets—that were created by expert artist-residents and hidden from the Nazis. Besides the terrible beauty of their mute testimony, these art works are additionally haunting due to the knowledge that their creators perished in the camps.

The other visuals belong to a Nazi propaganda film shot at Thereisenstadt during the war showing its residents, well-dressed (though all wear yellow stars) and apparently well-fed, going about their ostensibly wholesome daily routines. There are kids and old people and whole families, eating delicious-looking food, watching football matches and just relaxing. It makes a happy picture, unless you consider that most of the smiling actors were gassed not long after. (If the Nazis were bent on exterminating the Jews, why even bother making such a bizarre movie? Lanzmann’s film doesn’t address that, but in interviews he has said that it wasn’t aimed at the German public but rather at certain foreign audiences to whom the Nazis wanted to deny the reality of the Holocaust.)

Asked why he survived, Murmelstein, an erudite man who’s a fount of literary and mythological references, likens himself to Scheherazade, saying he was allowed to live because he had a tale to keep telling—the tale of “the paradise of the Jews.” He means the cruelly fictional paradise that the Nazis created at Thereisenstadt, but he perhaps was also spared to tell the stories he tells in this extraordinary and important film.

To be sure, the position of men like him was morally troubling and questionable. But it’s hard to argue with Murmelstein, who was tried by the Czechs after the war and acquitted of all charges, when he says, “An Elder of the Jews can be condemned. In fact, he must be condemned. But he can’t be judged, because one cannot take his place.”