In the Paris of the mob, during the French Revolution, a patrician British lady supports the monarchy and defies the citizens’ committees that rule the streets. She does this not in the kind of lame-brained action story we might fear, but with her intelligence and personality–outwitting the louts who come to search her bedroom, even as a wanted man cowers between her mattresses.

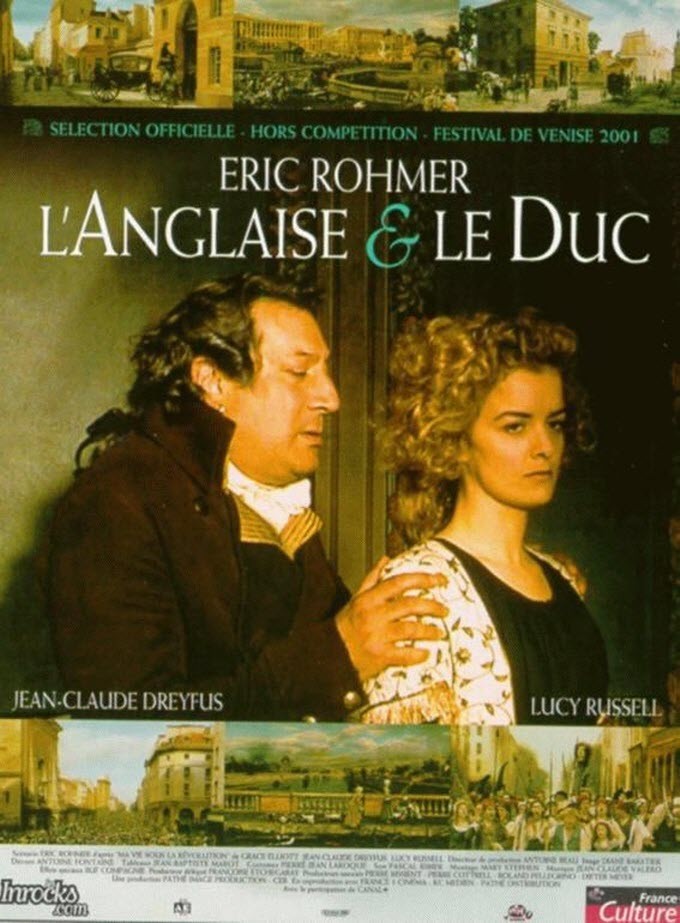

Eric Rohmer’s “The Lady and the Duke” is an elegant story about an elegant woman, told in an elegant visual style. It moves too slowly for those with impaired attention spans, but is fascinating in its style and mannerisms. Like all of the films in the long career of Rohmer, it centers on men and women talking about differences of moral opinion.

At 81, Rohmer has lost none of his zest and enthusiasm. The director, who runs up five flights of stairs to his office every morning, has devised a daring visual style in which the actors and foreground action are seen against artificial tableaux of Paris circa 1792. These are not “painted backdrops,” but meticulously constructed perspective drawings, which are digitally combined with the action in a way that is both artificial and intriguing.

His story is about a real woman, Grace Elliott (Lucy Russell), who told her story in a forgotten autobiography Rohmer found 10 years ago. She was a woman uninhibited in her behavior and conservative in her politics, at onetime the lover of the Prince of Wales (later King George IV), then of Phillipe, the Duke of Orleans (father of the future king Louis Phillipe). Leaving England for France and living in a Paris townhouse paid for by the Duke (who remains her close friend even after their ardor has cooled), she refuses to leave France as the storm clouds of revolution gather, and survives those dangerous days even while making little secret of her monarchist loyalties.

She is stubbornly a woman of principle. She dislikes the man she hides between her mattresses, but faces down an unruly citizens’ search committee after every single member crowds into her bedroom to gawk at a fine lady in her nightgown. After she gets away with it, her exhilaration is clear: She likes living on the edge, and later falsely obtains a pass allowing her to take another endangered aristocrat out of the city to her country house.

Her conversations with the Duke of Orleans (attentive, courtly Jean-Claude Dreyfus) suggest why he and other men found her fascinating. She defends his cousin the king even while the Duke is mealy-mouthed in explaining why it might benefit the nation for a few aristocrats to die; by siding with the mob, he hopes to save himself, and she is devastated when he breaks his promise to her and votes in favor of the king’s execution.

Now consider the scene where Grace Elliott and a maid stand on a hillside outside Paris and use a spyglass to observe the execution of the king and his family, while distant cheering floats toward them on the wind. Everything they survey is a painted perspective drawing–the roads, streams, hills, trees and the distant city. It doesn’t look real, but it has a kind of heightened presence, and Rohmer’s method allows the shot to exist at all. Other kinds of special effects could not compress so much information into seeable form.

Rohmer’s movies are always about moral choices. His characters debate them, try to bargain with them, look for loopholes. But there is always clearly a correct way. Rohmer, one of the fathers of the New Wave, is Catholic in religion and conservative in politics, and here his heroine believes strongly in the divine right of kings and the need to risk your life, if necessary, for what you believe in.

Lucy Russell, a British actress speaking proper French we imagine her character learned as a child, plays Grace Elliott as a woman of great confidence and verve. As a woman she must sit at home and wait for news; events are decided by men and reported to women. We sense her imagination placing her in the middle of the action, and we are struck by how much more clearly she sees the real issues than does the muddled Duke.

“The Lady and the Duke” is the kind of movie one imagines could have been made in 1792. It centers its action in personal, everyday experience–an observant woman watches from the center of the maelstrom–and has time and attention for the conversational styles of an age when evenings were not spent stultified in front of the television. Watching it, we wonder if people did not live more keenly then. Certainly Grace Elliott was seldom bored.