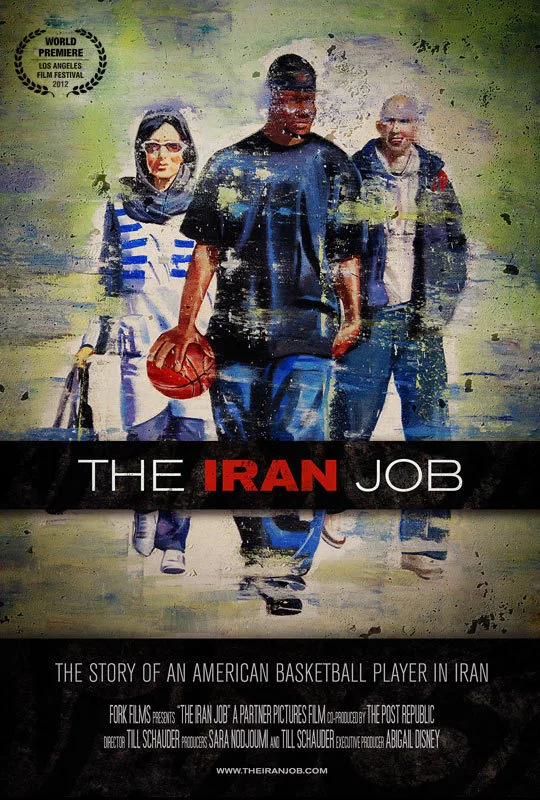

While in Poland last July, I learned of a film called “Czarodziej z Harlemu,” or “Magician From Harlem.” Its origins were Polish, but its plot was pure Hollywood: A foreign basketball team imports an African-American man named Abraham Lincoln to help them win a championship. Wackiness ensues, or so I’m told. The visions of “Magical Negro” dancing in my head kept me from seeking out “Magician From Harlem,” but its plot was the first thing I thought of when I heard about “The Iran Job.” The description sounds like a real-life fish-out-of-water tale crossed with a sports movie. But the film wants to be more than that, and I’m on the fence about how well it succeeds.

“The Iran Job” follows Kevin Sheppard, a St. Croix native who is recruited by an Iranian basketball team to help lead them to the playoffs. I don’t believe the team, A.S. Shiraz, hired Sheppard because of his skin color, but I did wonder if he had been the only candidate who accepted. It’s 2008, and as Sheppard’s relatives point out, Iran isn’t the safest place for Americans to be. “The Iran Job” never explicitly describes the recruiting process, but it clearly spells out the grounds for termination: If A.S. Shiraz doesn’t make the playoffs, Sheppard fouls out of the league.

I confess to being a sucker for sports movies, the ones with the “Big Game” at the end. “The Iran Job” has all the requisite elements of that cinematic subgenre, but strives for something deeper. A.S. Shiraz is the newest edition to the Iranian Basketball Super League, a promotion of sorts, so all eyes are on them to make history by becoming the first team to reach the playoffs in their first year. Iranian basketball rules allow for each team to recruit two foreign players from any country willing to send them. Sheppard is joined by a Serbian he calls Z; the two room together and are the most experienced members of the team.

The rest of the team is young and untrained. After their first practice session, Sheppard is stunned by their skill set, or lack thereof. “That was the worst [expletive] I’ve ever seen,” he tells the camera. The coach makes him team captain, but Sheppard soon realizes that the fans share his fired-up enthusiasm more than his teammates. Sheppard’s tenacity would play better in the league he failed to make after graduating Jacksonville University: the NBA. But here, “You get angry at them, and they play worse,” the coach basically tells him. Sheppard changes his captain’s plan of attack.

He also has to modulate his temper on the court; his angry tossing of a trash can after a close loss is carried by every channel in Iran and gets him in legal trouble. The fans can be rowdy, with the men on one side and the women on the other, but players are expected to play by the rules with no disciplinary issues. If the NBA had Iran’s strict rules of sportsmanlike conduct, half the players would be in jail.

As you’d expect, with Sheppard and Z’s help the team gets better. They start winning, and “The Iran Job” follows their peaks and valleys in brief vignettes. It’s comical how many games come down to last-minute shots or fouls, yet my sports loving Pavlovian responses sucked me into the suspense every time. The Iranian press and sportscasters take notice, especially of Sheppard, and the team’s fan base grows as they march toward a potential playoff spot. Helpful onscreen graphics chart the team’s rise and fall during the 24-game season, giving us the names of the other teams and their placement.

The top eight teams in the 13-team league will make the playoffs, a one-game elimination round much like the NFL’s. Documentaries don’t have spoiler warnings, so I can tell you A.S. Shiraz makes the playoffs. I can further tell you that, in continuing with real-life’s parallel track with sports movie cliché, A.S. Shiraz has to face last year’s champion and the toughest team in the league, Mahram Tehran. “We could get our asses blown OUT!” Sheppard tells the camera. I wouldn’t dream of telling you if they do.

“The Iran Job” is two documentaries in one: The sports aspect coexists with Sheppard’s observations of a foreign land. We know enough about basketball for those scenes to exist as shorthand while the Iranian elements are more fleshed out. Like Sheppard, the audience is learning about a country through dialogue and experiences. These two parts of “The Iran Job” complement each other, sometimes essentially so, but there are instances where there’s a jarring dissonance. Writer-director Till Schauder nicely underplays the outcome of the Big Game, but also mishandles a crucial news item revelation the movie had quietly been building toward.

Schauder keeps us at arm’s length from some of the people who populate “The Iran Job.” Sheppard remains something of an enigma the entire film, even though he’s talking to the camera. In fact, most of the men merely exist, with only occasional fleeting glimpses into their psyches. For example, Z talks to Sheppard about the horrors of being in Serbia during days and days of bombing, but the conversation is reduced to a few vague lines of narration. Sheppard plays matchmaker for a team member, and counsels another whose girlfriend has dumped him, but neither of these incidents are allowed to blossom into meaningful interactions between teammates.

“The Iran Job” gets much more mileage from its female subjects. Despite being a disembodied voice for most of her scenes, Sheppard’s girlfriend does a lot to define herself for viewers. Her discussions with Sheppard and, at the beginning of the film, with us, allow us to get to know her, and to see Sheppard through her eyes. “He tells me everything he’s going to do at the last minute,” she says, “so that I don’t have time to react, or to cuss him out.”

We also meet Elaheh and Laleh, two Iranian women and the most interesting people in the film, who befriend Sheppard and serve as vessels of information for us. Allowing them to describe how they feel about their homeland is the secret weapon of “The Iran Job.” Their navigation of the rules of male-female interactions, and their independent, outspoken views, keep “The Iran Job” from descending into another tale of The Other as seen through our eyes.

Sheppard is surprised (as are we) to discover how these women, who deal with so many rules about their conduct and appearance, manage to be anything but downtrodden and dejected. Reports of the unrest going on during Sheppard’s tenure seem destined to connect with the outspoken passions of Elaheh and Laleh; when they indirectly do, “The Iran Job” does a sloppy job handling it. It’s almost a throwaway moment in the film.

Like I said, I’m on the fence here. I’ve watched the film twice, and both times, I wished I’d gotten either the sports documentary or the life-in-Iran documentary. Combining them seems to give both halves short shrift, despite strong moments in each.