Claude Berri’s “The Housekeeper” opens with a leisurely survey of a Paris apartment. The place is a mess. Dirty laundry, unmade beds, clothes thrown anywhere, the man sleeping on a couch and then stumbling to his bed in the middle of the night. His wife has walked out, and he needs a housekeeper. He finds a notice in a store, calls the number on the little tag of paper, and finds himself in a cafe having coffee with a young woman who says she will be happy to take the job. She is young, sexy in a certain light, says she has not worked as a housekeeper before but needs the job and will work hard. He hires her. We might cynically assume he has erotic thoughts in the back of his mind, but apparently not: He scarcely seems to notice her, and at first arranges for her to work during hours when he is not at home.

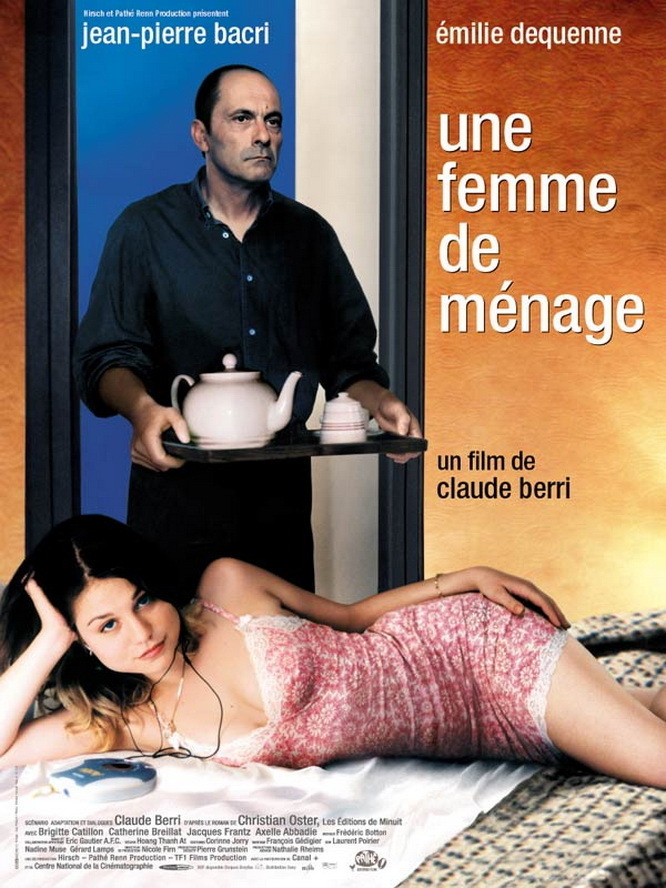

He is Jacques (Jean-Pierre Bacri), a serious man in his 50s, balding, good-looking, masculine, preoccupied, busy. She is Laura (Emilie Dequenne), has two-tone hair, the roots growing out, and seems a little sloppy, but she does a capable job of cleaning the apartment and very slowly, with instinctive craft, she expands her role in his life, insinuating herself, being useful in unexpected ways, doing some of the domestic things a wife might do–and eventually, all of the things a wife might do. That he sleeps with her is more a result of his capitulation than his lust. Soon he hears the momentous words “I love you,” and the crucial question, “Do you love me?” and the camera is looking directly at his face as he agrees, not with enthusiasm, that he does.

He doesn’t love her, of course; his emotions are a mixture of pity, gratitude, fondness and lust, but men have ineffective defenses against tears and sex. With the same application she brings to the housework, she elevates herself from housekeeper to that undefined sort of female companion that his friends think they understand, even though they do not.

There is a vacation trip to visit an old friend of his. She comes along. She is soon wearing a ring, and there is a story behind the ring, which I will not reveal, but which helps to define the gulf between his adult life and this accidental liaison that is almost certainly going to be more trouble than it’s worth. A confrontation with his friend reveals how much more important his wife is, even absent and despite his resentment, than the girl who shares his bed. (We get a few glimpses of the wife, played by Catherine Breillat, the director of such more harrowing examinations of sex as “Fat Girl” and “Romance.”) Many movies celebrate romances between older men and younger women. That is because most movie directors are older men, and find such stories congenial and plausible. In their eyes older men are more attractive, irresistible, fascinating, than the callow boys the same age as their young partners. What these movies often fail to observe is that their young lovers are callow, too. When you are 40 or 50 or 60, to sleep with a girl of 20 might indeed be delightful, but to live with her day in and day out might be an ordeal beyond all imagining.

There is, first of all, the business of dancing. Young girls want to stay out very late and dance endlessly to barbaric music. Mature men are amused to spent a little time on the dance floor–but not hours and hours and hours, surrounded by inexhaustible youth, the music so loud they can make no use of their treasured conversational abilities. They do not understand, or have forgotten, that the whole point of loud music is to make it possible to date without talking. There are other problems. Girls want to swim when the water is too cold. They want to sunbathe far beyond any reasonable period that a person with an active mind can abide remaining prone on the sand. They have limited interest in spending hours listening to the older man and his old friends remembering times and people they will never ever know for themselves.

“The Housekeeper” is wise and subtle in the way it presents its older man. A less interesting movie would make him lustful and self-deceiving, a man who believes his is the secret of eternal youth and virility. In the case of Jacques, however, he goes along, up to a point, indulges his weakness and his curiosity, up to a point, and then he finds that point–or, more poignantly, has it pointed out for him. The closing shots of the movie, which use Jean-Pierre Bacri’s face as their primary canvas, say all that needs to be said about what he has learned, and with what wry acceptance he has received the message.