There is a kind of movie sequence which Alfred Hitchcock always did well, and which most later directors have chosen not to do at all.

It involves the hero discovering information by being nosy. Little or no dialogue is used. Most of what the hero sees is in long shot, and we can sometimes not quite make out all of the details. Half-heard words float on the air. What is being spied on is none of the hero’s business, but he cannot resist the human need to be a spy, and neither can we.

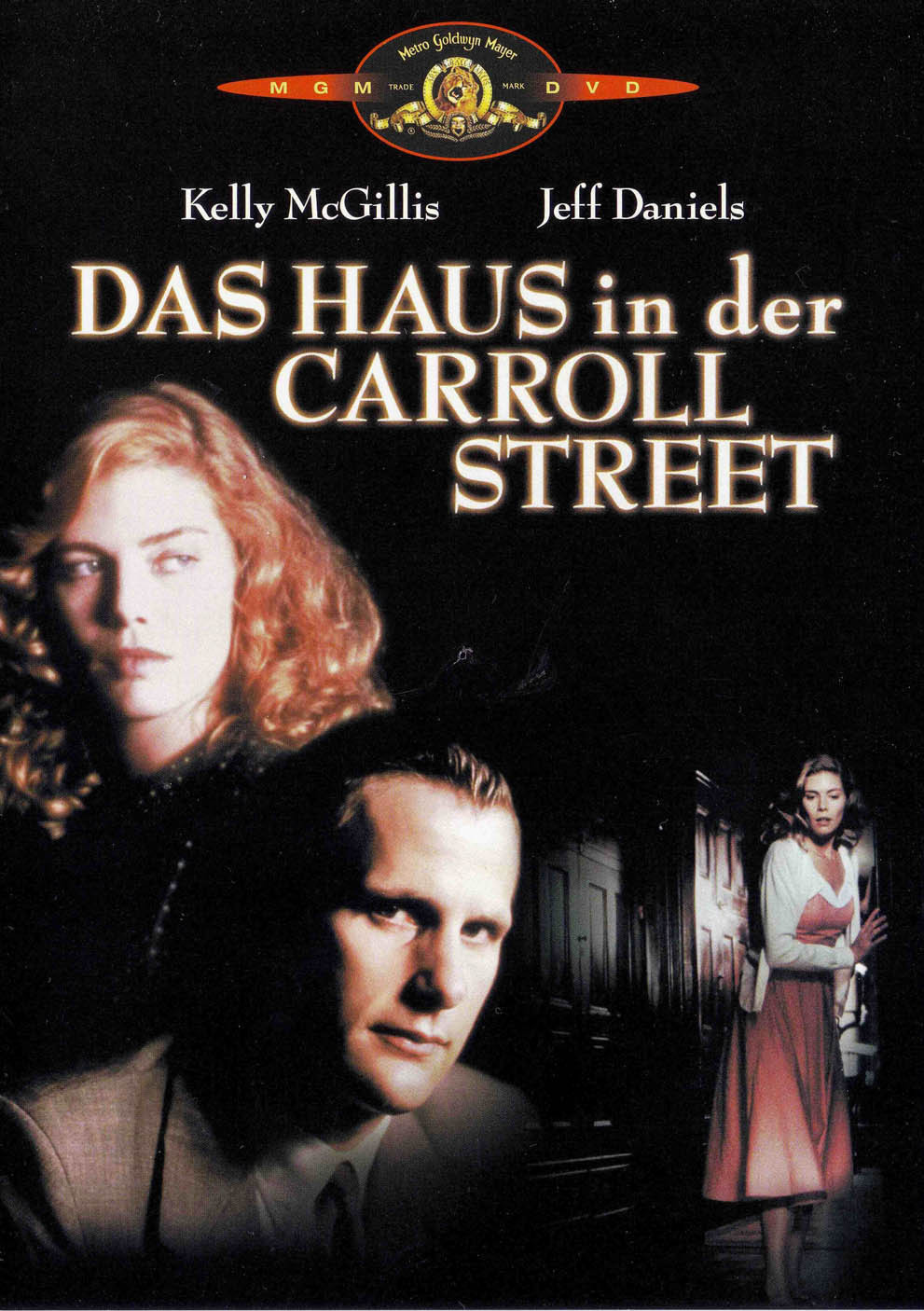

The crucial developments in “The House on Carroll Street” are established with such a sequence, and so well is it handled that it casts a sort of spell over the movie. The time is the early 1950s, the height of McCarthyism. The heroine (Kelly McGillis) is a young woman who has just lost her job at a magazine, after refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Desperate for work, she takes a job reading aloud to an old lady. One afternoon, walking in the lady’s garden, she sees some figures moving in the tall back windows of the house on the other side of the yard.

She is intrigued. She moves closer, hiding behind the branch of a tree. She overhears an argument. She can tell that something is wrong but does not know what it could be. Later, on the street, she sees a young man who was standing in the window. She tries to engage him in conversation, but he resists. Eventually, piecing together a clue here and a word there, she becomes convinced that the people in the house are smuggling Nazi war criminals into the United States and that they have friends in high places.

There is more. Because the McGillis character is presumably a dangerous radical, she is being tailed by the FBI (there is a hint here of the opening scenes of “Notorious”). The important friends of the Nazis might want to smear her as a Commie to confuse the trail. The Nazis begin to suspect what she knows. The old lady becomes a valuable ally. And in another echo from “Notorious,” she and one of the FBI men fall in love.

He’s played by Jeff Daniels, that dependable, open-faced middle American from “Something Wild” and “Terms of Endearment.” Hey, maybe she is a Commie, but she sure is pretty. He is attracted to her, is disturbed when she is harassed by a search of her home, begins to trust her, and eventually becomes her ally in the fight against the Nazis and their protectors.

As thriller plots go, “The House on Carroll Street” is fairly old-fashioned, which is one of its merits. This is a movie where casting is important, and it works primarily because McGillis, like Ingrid Bergman in “Notorious,” seems absolutely trustworthy. She becomes the island of trust and sanity in the midst of deceit and treachery. The movie advances slowly enough for us to figure it out along with McGillis (or sometimes ahead of her), and there is a nice, ironic double-reverse in the fact that the government is following a good person who seems evil, and discovers evil people who seem good.

What is particularly welcome about the movie is that it’s not high-tech. It not only takes place in the 1950s, but is happy there. We don’t get the slam-bang cynicism of most characters in modern movies, and after awhile I began to figure out why. This movie takes place so long ago that the characters in it have never had their imaginations boiled by full immersion in the thriller culture of recent decades.

They’re still sort of sweet and innocent, and believe everybody is basically good, and are shocked when they’re wrong. Maybe that’s the movie’s ultimate twist.