“The Hospital” is a better movie than you may have been led to believe. It has been criticized for switching tone in midstream, but maybe it’s only heading for deeper, swifter waters. It begins as a farce, and one of the tricky things about farce is its tendency to get hysterical while trying to top itself. Paddy Chayevsky has worked around this neatly by keeping his farcical elements as a subplot while steering his main story down a long, lonely night with a strange doctor and an even stranger woman.

The movie opens with hospital scenes that seem to suggest the “MASH” gang was demobilized and went into private practice. For starters, a diabetic intern is unlucky enough to fall into a snooze after making love to a nurse on a hospital bed. He is assumed to be the late occupant of that bed, and is inadvertently killed by an intravenous feeding. That is only a beginning. By the next morning, a nurse and two doctors will also be dead, mostly because they were wearing the wrong ID bracelets at the wrong time.

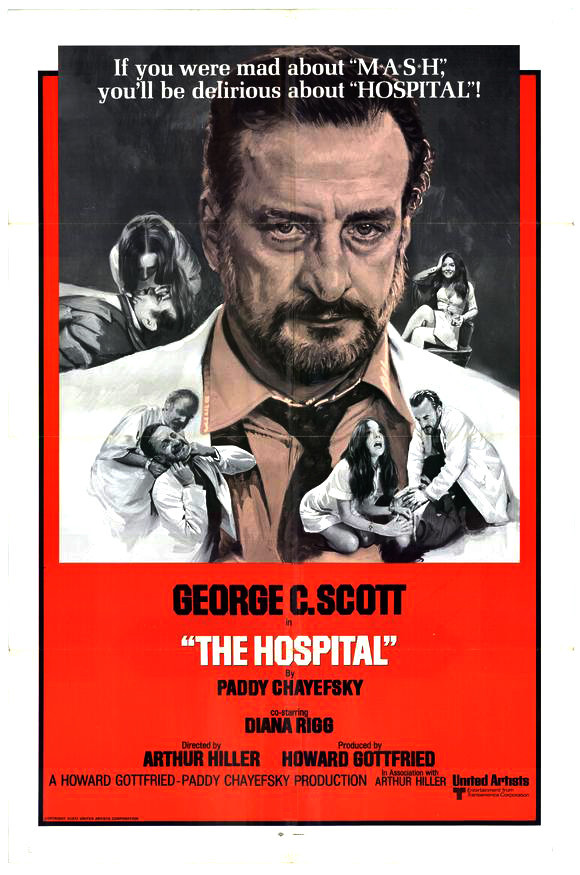

Presiding over this mess as chief of staff, George C. Scott hardly cares. He has left his wife, thrown his “shaggy-maned Maoist” son out of the house, entertains suicidal fantasies, and spends his nights in dour communion with a quart of vodka. During the movie’s first half, he is a character something like the Jack Davis cartoon caricatures in the ads, but by the movie’s middle, as the hospital falls to pieces about him, a strange thing happens.

He meets a girl. Not just any girl, but Diana Rigg, an ex-SDS, ex-acidhead, ex-nurse who lives with her dotty father among a tribe of Indians in Arizona. The moment she opens her mouth, we’re sure she’s going to be another of those dime-a-dozen eccentric young girls who clutter up otherwise sensible plots these days. But no, she is there to lead the plot into its long, lonely night, which contains some of the best writing Chayevsky has ever done.

Failed in a suicide attempt as in (it seems) everything else, Scott listens to the girl’s story and then tells his own. Their monologues, told in the dimly lit and claustrophobic doctor’s office, use good writing, acting and direction to move the movie away from the farce of the day and into the nighttime of fear that farce sometimes conceals. Their meeting may seem at first like just another case of Lonely Man Meets Right Girl, but before long it gets a lot more complicated than that.

The morning after is filled with crackpot mystical revelations; neighborhood activist demonstrations and strange coincidences that are explained in somewhat arthritic flashbacks. It’s here that we begin wishing again that Chayevsky and director Arthur Hiller had stayed with the farce – had let Science murder the victims, instead of Art.

But in a way, the movie’s ending is part of its beauty. If we were left believing the hospital had mindlessly and inadvertently committed murder, we’d be back on the humanist team in the war against expertise. As it is, Chayevsky’s bizarre and unexpected ending suggests that men – even madmen – can still use institutions for their own private purpose.