Harold Pinter’s “The Homecoming” almost cried out to be filmed, unlike so many plays that seem stagy or claustrophobic as films. It works even better – because it IS stagy and claustrophobic. And because it depends for its effect on sometimes minute adjustments among a family at war, the camera helps by getting us so close we sometimes want to duck.

It’s a difficult play, one that has never been very popular with audiences – but seeing it as a movie helped me understand it better than I’ve ever been able to before. If this is what Ely Landau means when he says his American Film Theater will present movies based on stage plays – and not merely photographed plays – then the AFT has come through on its first try.

The play takes place during one interminable day and night in a drab Cockney flat in London. Drab is the word, all right; the movie is in color, but the sets are deliberately ugly variations on white, gray and black (and so are the souls of the characters). We’re introduced to a family: Max the patriarch, his sons, Lenny the pimp and Joey the would-be boxer, and his brother Sam the chauffeur. These people hate each other with a violence and depth that must have taken long, bitter years to perfect.

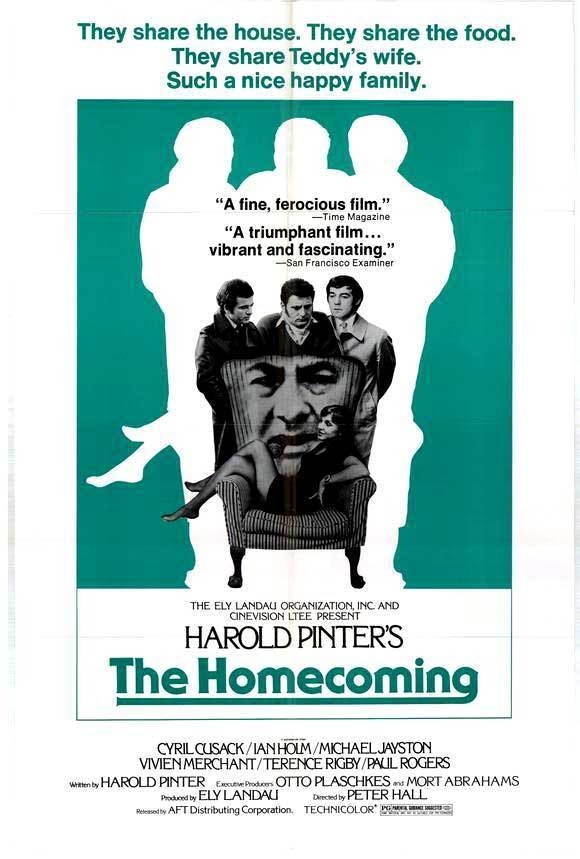

It’s literally a household: The house holds them in like a psychic prison. They turn on each other because there are no other targets. Distant reports are received from the outside world; a box of cigars, for example, is presented as a gift from one of Sam’s customers. But somehow we can’t believe there’s anyone outside; these are the last people alive, like Vladimir and Estragon in “Waiting for Godot.” Then, almost shockingly, two more characters appear: Teddy, a third son, who is a teacher of philosophy in America, and Ruth, his wife. The family has never met Ruth before, but they pounce on her with sadistic glee, accusing her of being a prostitute and not a very expensive one at that. Teddy halfheartedly defends his wife, but before the play is over (a) he has decided to return to America alone; (b) she has agreed to stay as the resident sex object for the other males in the family and turn a few tricks on the side, and (c) Sam has collapsed on the floor, making it necessary for the others to step around him while giving the final twists to their psychic thumbscrews. Peter Hall, who did the original production for the Royal Shakespeare Company, has assembled many of the original cast members (Cyril Cusack is new), and they are so fierce with Pinter’s words that even the silences hurt. No effort has been made to “open up” the play just because it’s a movie now; the two or three exterior shots aren’t for the scenery but to show us what we suspected all along: The London outside is an abandoned ruin bathed in a hellish red glow. So we admire the movie’s technical excellence but are left with the problem of what it all means.

The movie’s meaning is in the experience we have while we’re watching it. I think. Pinter has a single purpose: To create uncomfortable emotional states within us, to fabricate for us (against our will, if necessary) a cluster of painful feelings.

“The play is about love,” he explained, not very helpfully, back in 1967. When you think about it, he’s right. The play is about love the way night is about day. The one has no meaning without the other. The play is an enclosed sphere with love on the outside. Determined realists are still left with such questions as, why doesn’t Teddy object when Joey is having at Ruth on the living room couch while everybody watches?

The answer, I guess, is that if you expect Pinter characters to react decently, you’re a lot more of an optimist than he is. These people are so far beyond decency, they can’t even joke about it, because they’ve forgotten it.

It’s weird. The most improbable things happen in “The Homecoming,” and its characters treat each other with total contempt, and yet somehow we ARE moved.

We don’t think we will be; we spend the first half of the movie trying to reject its premises, but then Pinter sucks us in. We realize, consciously or not, that the people in that room have to care about each other very much, in order to hate each other so thoroughly. One aspect of love is, perhaps, to value another and what would these sadomasochists do without their laboriously maintained relationships? They’d be at a loss. Here’s a movie about dependence and need and . . . love?