If “The Grief of Others” were a person, it would be the kind that always replies, “Nothing,” when you ask what’s wrong, even when it’s obvious that something is very wrong.

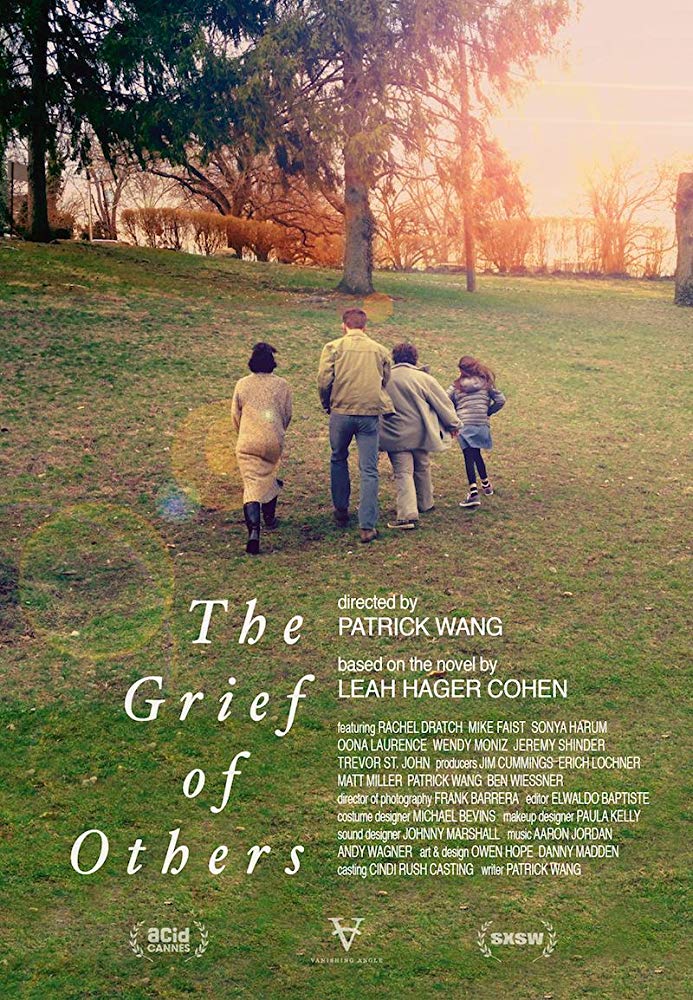

Adapted and directed by Patrick Wang from the same-titled novel by Leah Hager Cohen, the film is about a suburban family in upstate New York dealing with a sudden death in the family. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that they aren’t dealing with it—that might be the real root of the problem, of course. But it’s also an inevitable response to trauma, and Wang’s movie is empathetic enough not to pass negative judgment on the characters as they muddle through their experience.

Ricky and John Ryrie (Wendy Moniz and Trevor St. John) are a married couple with two kids, an elementary school-aged daughter named Biscuit (Oona Laurence) and her older brother Paul (Jeremy Shinder). The film tells us what happened to them a bit more quickly than you might expect, considering the story is told in a restrained, elliptical, at times obscure way. A lifetime of moviegoing primes you to think this’ll be another one of those films that withhold the most important facts until the very end, to fuel a cathartic moment, or just to keep you on the hook emotionally. But that’s not what Wang has in mind. He uses the event the way a surgeon uses a scalpel, cutting up the narrative according to what characters realize about each other and themselves—and when they realized it.

The movie begins with an orange-tinted, first-person deathbed flashback where you don’t know who died, then moves immediately to an oddly framed scene of Biscuit skipping school on a rainy day and falling into a river. From there, we get a series of scenes covering the arrival of teenaged Jess (Sonya Harum), John’s daughter from his previous marriage, as well as the simultaneous introduction of 19-year artist Gordie Joiner (Mike Faist), who rescued Biscuit from the river, feels guilty that his dog accidentally bumped her into the water in the first place, and is still in grief himself from losing his dad.

“The Grief of Others” is most fascinating when it shows what the suppression of pain does to relationships. This is partly expressed through the art that some of the characters create—John is a set painter and Paul an aspiring comics illustrator, while Gordie makes dioramas—but mainly through scenes of people avoiding the most pressing issues in their lives, talking around them, or engaging in diversionary acts of self-destruction.

The spine of the tale is the marriage of Ricky and John, which was apparently chugging along pretty well until the loss detonated within it, sweeping away ordinary rituals and affirmations that held the couple and their kids together, and exposing basic differences in personality and worldview that might be irreconcilable. Specifically, John is angry about secrets that Ricky has withheld from him, as well as the way she tends to make major decisions for both of them without consulting him first. Ricky defends this tendency by saying that she knows John well enough to predict what he might’ve done or wanted. She’s not wrong about this, and John even admits as much in one of the film’s many heated arguments.

But John is also correct to say that knowing or not knowing isn’t the point—that it’s about being considerate and making the other person feel like a full partner. Anybody who’s been in a long-term relationship will relate to the way that John and Ricky talk over and past each other, not just to each other, as well as they way they tend to answer what they believe to be the passive-aggressive subtext of a question, rather than simply answering the question.

This is pretty ordinary partnership stuff, but it acquires a frustrated, at times agonized edge in this context, with parents and their kids trying not to fall into the abyss of mourning that follows them everywhere. “The Grief of Others” is unerring when it’s sticking to the main couple, and they’re incarnated with great skill by Wang’s lead actors. Moniz is wizardly at playing moments where her character seems to have no idea that she’s even made a mistake, much less how devastating it was. In the many scenes that involve alcohol, St. John plays one of the most realistic drunks I’ve seen in a long time, stumbling through his thoughts and realizing that he made an incorrect or nonsensical statement several seconds after the words leave his lips. He also captures that specific type of cultured and “sensitive” man who often blurts out hurtful remarks the second they enter his head, falsely assuming that if he apologizes quickly enough, it’ll neutralize the pain he just inflicted.

But “The Grief of Others” falters whenever it tries to flesh out the supporting cast. And that’s unfortunate, because the movie seems to be shifting its attention away from John and Rickie because it’s genuinely curious about the other characters and looks at drama as a democratic exercise, where the point is to take as many points-of-view into consideration as possible. This is a relatively brief movie to carry such weighty themes, clocking in at less than two hours; but there are many moments where it feels as if it should have been longer or shorter, because the marvelous, stand-alone scenes (such as Paul staring silently into space while a past conversation plays on the soundtrack, or Gordie showing Jess the elaborate dioramas he made to deal with his father’s death) seem to hint at a wealth of detail and nuance that the movie’s not equipped to provide. As a result, we end up thinking of these secondary players in very general terms: Paul and Biscuit as troubled kids (him acting out, her internalizing), for instance, and Jess and Gordie as genuinely nice people with healing instincts, and so on.

It also doesn’t help that the movie’s arms-length direction keeps us from fully connecting with the characters. This is admittedly deliberate on Wang’s part; it makes it seem as if the film itself is in denial, constantly averting its own gaze from the truth, but gradually sorting its issues out as it moves towards some kind of breakthrough, however messy. But the framing, while admirable from a philosophical standpoint, makes the movie feel more fragmented and schematic than it really is—as if it’s an intellectual exercise rather than the thoughtful and kindhearted movie Wang has made. Most of the scenes consist of just one angle that plays out in a long take with no cuts; a lot of the time you only get a good look at the face of one character in the scene, even though two or more might be talking. There are entire scenes that play out in a wide shot, where we’re seeing characters argue from a distance. An intense confrontation between Biscuit and her father is staged in a bathroom, with the girl framed by an open doorway and John yelling offscreen.

I admit this is a case where I wanted something from a movie that it simply wasn’t going to give me, and that your mileage might vary a lot. But that doesn’t change the fact that (in contrast to two Wang’s other two features, “In the Family” and the two part “A Bread Factory,” which I adored, and which are shot in a similar manner) there were stretches where it felt as if the style was a delicately embroidered pillow that the story was crying (or screaming) into, long after the film had earned the right to just let it rip.

Nevertheless, this is an unusual and involving if sometimes demanding and difficult movie, as well as one where form and function are matched with crystalline precision. Fans of the director’s other movies will want to see it regardless, to watch an American master’s style in the process of evolving.