‘The Gospel” is the first mainstream movie I can remember that deals knowledgeably with the role of the church in African-American communities. It is not a particularly religious movie; the characters are believers, but the movie is not so much about faith and prayer as about the economic and social function of a church: How it operates as a stabilizing force, a stage for personalities, an arena for power struggles, and an enterprise which must cover its costs or go out of business.

The counterpoint for all of this drama is gospel music, a lot of it, performed by such well-known singers as Yolanda Adams, Fred Hammond, Martha Munizzi, the “American Idol” finalist Tamyra Gray, and by inspired gospel choirs in full praise mode. If the plot wanders through several predictable situations, and it does, the movie never lingers too long on those developments before cutting back to the best gospel music I’ve seen on film since “Say Amen, Somebody.” Like an Astaire and Rogers musical, this is a movie you don’t go to for the dialogue.

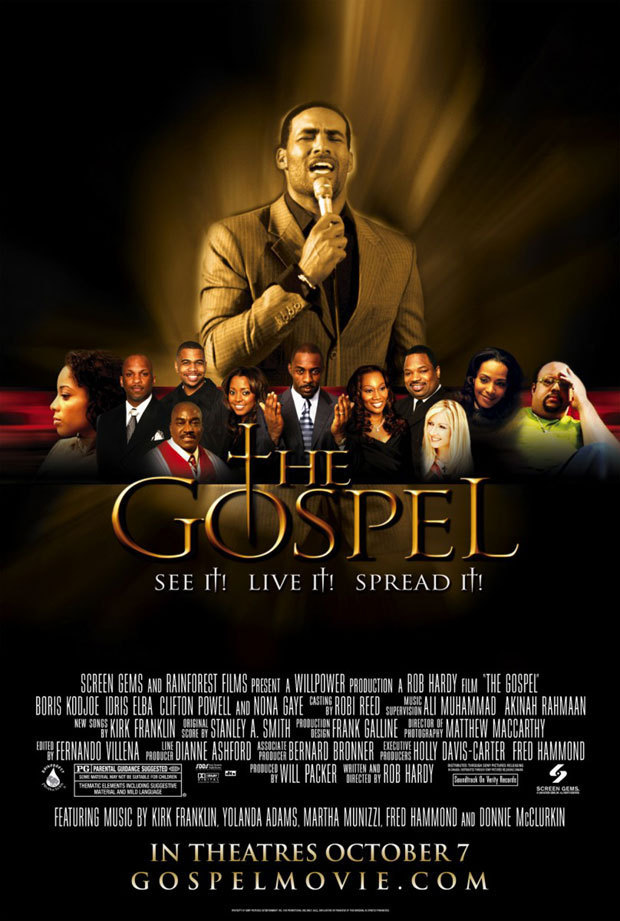

As the story opens, Pastor Fred Taylor (Clifton Powell) presides over a thriving church in Atlanta. His son David and David’s best friend Frank are both in the youth ministry. Flash forward 15 years. David, now played by Boris Kodjoe, is a rising hip-hop star with a hit on the charts: “Let Me Undress You.” Frank (Idris Elba) is an associate minister. The church is having financial problems, and must close in 30 days unless funds can be found. At a meeting of a board of church overseers, Pastor Fred collapses. His son flies home to be at his bedside, gets the bad news, and is soon enough at his funeral.

Before his death the old pastor turned the pulpit over to Frank. There was some jealousy among more veteran pastors, but that’s nothing compared to the way David feels when he sees the big billboard out in front of his father’s church, showing David with the motto: “A new church, a new man, a new vision!” It doesn’t help that Frank has married Charlene (Nona Gaye), David’s cousin.

Will David return to his concert tour? His friend and manager Wesley (Omar Gooding) certainly hopes so: They’ve struggled a long time to get on the charts, to get the limousines and the hotel suites and the big crowds and such perks as the groupie David wakes up with the morning he gets the bad news about his father’s health. Yes, David is a sinner, but he’s not into drugs or booze, and it becomes clear, as his brief trip to Atlanta stretches to a week and then longer, that his spiritual life is calling to him. For Ernestine (Aloma Wright), his father’s church secretary for many years, Frank is an interloper, and David belongs in the pulpit.

The plot plays out in terms of David and Frank’s personal and professional rivalries, with the deadline for foreclosure looming always closer. None of these details, in themselves, are particularly new or interesting. What is new is the way the church is seen not in purely spiritual terms, but as a social institution. Rob Hardy, who wrote and directed “The Gospel,” obviously knows a lot about black churches, their services, their music, their traditions and the way the congregation interacts with the people on the altar. There are times here where call-and-response shades into put up or shut up.

I am not an expert on African-American church services, but I have attended some, at Bishop Arthur Brazier’s Apostolic Church of God and at the Rev. Michael Pfleger’s St. Sabina’s, and I appreciate the way the choir acts as a soundtrack for the service, softly coming up under the preacher’s exhortation, taking over, backing down for more preaching, its body language expressing as much joy as the music, the congregation fully involved. It is accurate that you see some white faces in the congregations in this film: To recycle an old British advertising slogan, these services refresh parts the others do not reach.