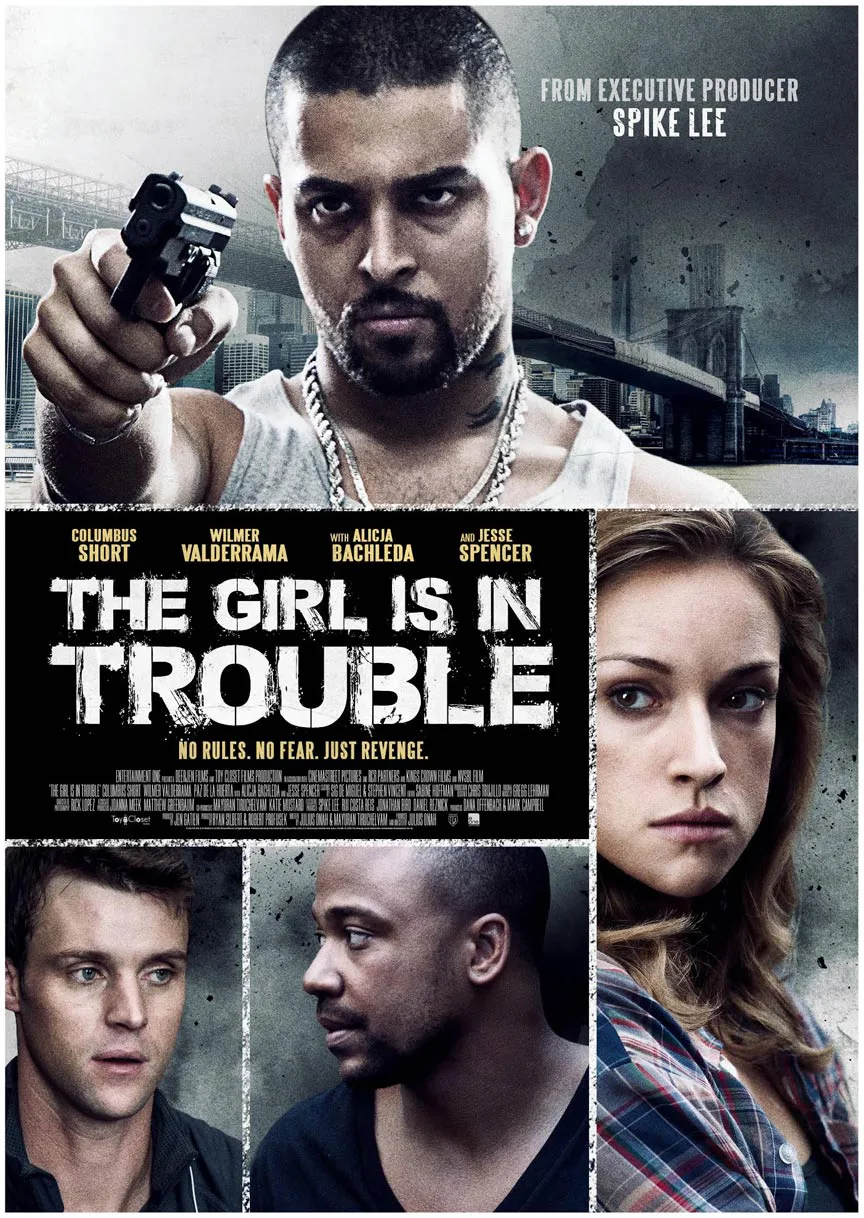

Filmmaker Julius Onah is a Nigerian-American who has lived in the Philippines, Nigeria, the United Kingdom, and now calls New York City his home. To say he has a unique socio-cultural perspective to offer the noir genre would be a massive understatement. However, the fact that he injects his remarkably promising debut “The Girl is in Trouble” with an undercurrent of commentary about class and race isn’t the only thing that makes it promising. It’s tightly directed and well-performed, particularly by Columbus Short and a career-redefining turn from Wilmer Valderrama. If anything—and trust me when I tell you this is the opposite of most independently produced noirs from debut directors—there’s an overabundance of ideas in “The Girl is in Trouble,” sometimes to a distracting degree. And Onah doesn’t quite stick the landing narratively, although he has such filmmaking energy that his work here merits comparison to that of the film’s executive producer, Spike Lee.

The most similar film in Lee’s filmography to this would be “Inside Man,” a highly underrated, brilliant piece of work in which Lee injected social commentary into what could have been merely another cookie-cutter thriller. Similarly, “The Girl is in Trouble” looks like just another Wrong Guy, Wrong Girl piece on first glance, but there’s much more beneath the surface. It’s no accident that the four central characters on which this thriller spins are from four vastly different backgrounds. There’s August (Short), a Nigerian-American struggling bartender/DJ, who gets what he thinks is just another booty call from a gorgeous Swede he met at a club named Signe (Alicja Bachleda). It’s no spoiler to say that Signe is the title character, as earlier that night she happened to be in a closet filming a murder on her cell phone, and she’s looking for a place to hide.

August wakes up from his night with Signe to find her going through his wallet. He responds understandably, grabbing her phone to call the police, and, of course, stumbles upon the smartphone version of a snuff film. The victim is a low-level dealer named Jesus (Kareem Savinon) and the murderer is the son of a powerful financial figure in New York named Nicholas (Jesse Spencer). Or is he? What exactly happened that night? And can August figure it out before either Nicholas or Jesus’ crazy brother Angel (Wilmer Valderrama) finds them?

The characters in “The Girl is in Trouble” may come from distinctly different backgrounds but Onah unites them in a vision of people trying to grab their part of the American dream, and he does so through the lens of noir. Onah never allows the social commentary to overtake the tension of the narrative, but he also never forgets about it. It’s a script that takes diversions for history lessons about immigration, asides about Nicholas not tipping his black server, who happened to be August. A memory of August being arrested three years ago for punching a yuppie who flicked a cigarette at him. The fact that he’s too broke to see a doctor. It’s a film about people not just looking for money, but a place in this world, and Onah is careful to mark what they have in common as much as how they’re different (it’s no coincidence that music plays a major part in the lives of August, Signe, and Nicholas).

One can feel Lee’s touch at different times throughout “The Girl is in Trouble” as Onah even cribs the trademark dolly shot in which his protagonists look like they’re floating—and he does so effectively given the themes of people detached, looking for solid ground. Onah also deserves credit for really paying off the big moment—the flashback to the night of the murder. It’s perfectly blocked, timed, and edited to produce maximum tension. We seem to rush too quickly from that memory to the credits, but that’s a minor complaint.

Cast is uniformly strong here, especially Short, who makes a likable leading man, and a surprisingly malevolent turn from Valderrama, an actor not really known for playing villains. He’s believably menacing to the point that you forget that this is casting against type after only a couple minutes. And he smartly imbues Angel with a sense of sadness at what he feels he has to do to avenge his brother. Like so many of these people, the predicaments of their life—whether it’s Signe’s drama, Nicholas’ Bernie Madoff-esque criminal father, or August’s job troubles—are not ones they have chosen. Although the end of “The Girl is in Trouble” spins even that on its head, arguing that responsibility and owning your life is the key to happiness. You don’t really find a place in this world, no matter where you come from, until you choose to take it.