The first ten minutes of “The Final Conflict” are such a masterful job of storytelling that I dared to hope that the “The Omen” trilogy had pulled itself out of the bag. The story is told in images without dialogue. An earth-moving machine in Chicago digs up seven ancient daggers. A workman carries the daggers home and pawns them. An antique dealer buys the daggers from the pawnshop. They go on auction and are eventually carried to an old monastery in Italy, where the abbot solemnly prays before them. These are the daggers, we learn, that are necessary to kill the antichrist.

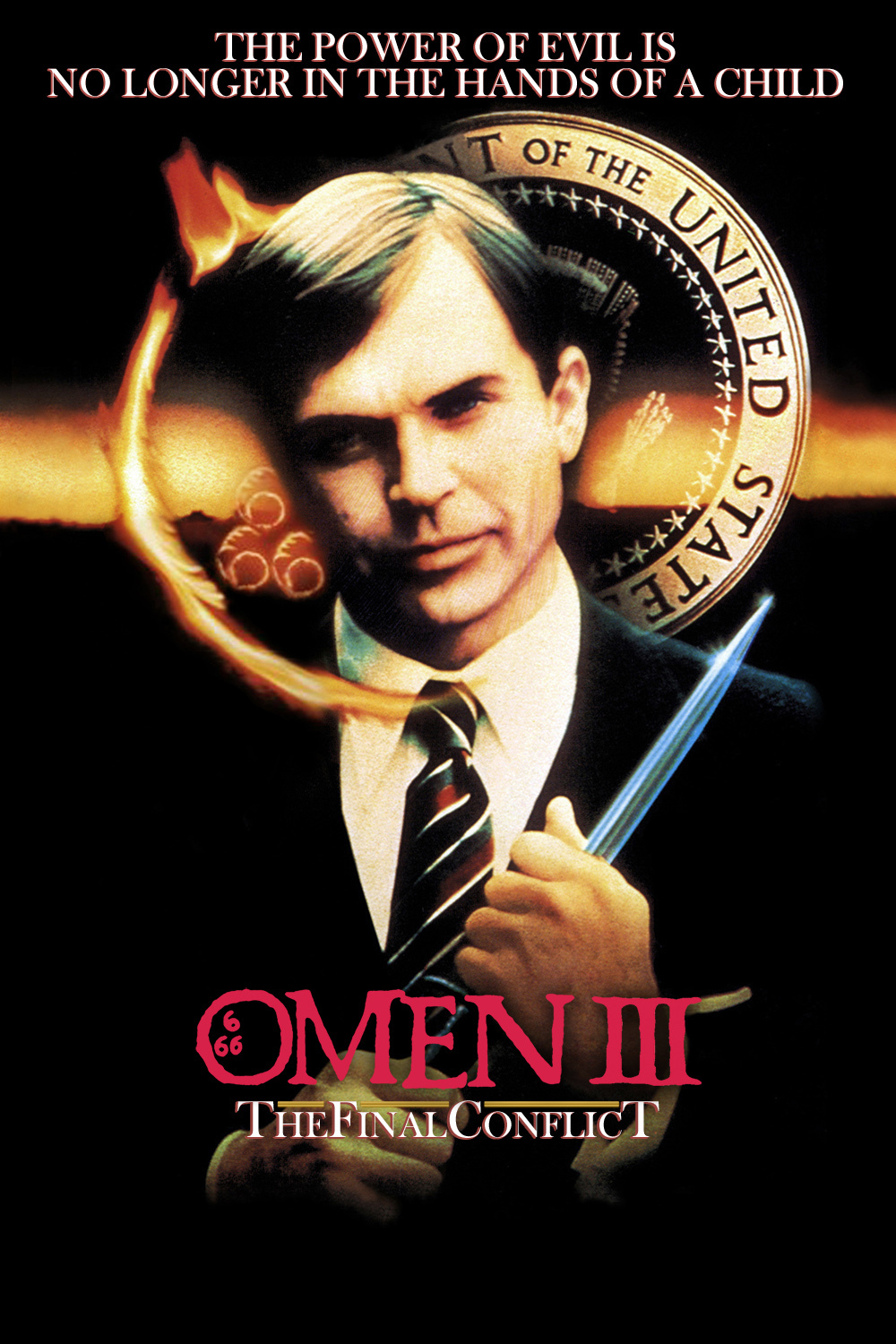

This is a terrific opening. But, alas, the moment “The Final Conflict” turns to dialogue and a plot, it loses its inspiration. If Armageddon is as boring as this movie, we’ll need a program to tell the players. Loyal students of the “The Omen” trilogy will know, of course, that this final conflict has been brewing for a long time, ever since 1976, when the original and rather effective “The Omen” was released. In that one, the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain adopted a child who, we learned, was the devil reincarnate. In “Damien: Omen II” (1978), the kid grew up, went to a military school, and set the stage for his eventual confrontation with the forces of good. A subplot was introduced, involving Thorne Industries, a multinational conglomerate with plans to dominate mankind by controlling the Third World’s food supply. As “The Final Conflict” opens, the adopted son (now played by Sam Neill) is in command of Thorne Industries, and is himself named ambassador to Great Britain, as well as chairman of the United Nations Youth Committee.

He does not make a very good youth chairman. Shortly after moving to England he learns that Christ has been reborn, and orders his flunkies at Thorne to kill all the male children born between midnight and 6 A.M. on the suspected day. That includes the son of his most trusted assistant, but so carelessly is this movie assembled that we’re never quite sure if the associate (a) knows and believes his boss is the son of Satan, (b) is a diabolical creation himself, or (c) is just on the payroll. Somebody on the staff must be in full sympathy with Damien, however, because in the attic of the U.S. Embassy in London’s Berkeley Square he has a room devoted to the Black Mass, including a grotesque wooden effigy of the crucifixion. I found myself thinking irreverent thoughts, like, what did they tell the movers as they were carting that crucifix upstairs?

So it goes. In addition to its opening sequence, “The Final Conflict” has one other great scene involving a fox hunt and a plot by the priests of the Italian monastery to lure Damien away from the hunt and kill him. This scene is wonderfully staged and edited. But the movie is otherwise a growing disappointment, as we realize that the apocalyptic confrontation between the forces of good and evil is being reduced to a bunch of guys with Italian accents running around trying to stab Damien in the back.

I would not, of course, dream of revealing this movie’s ending. But it’s not cheating to say how disappointed I was, as Damien slinks through an abandoned cathedral screaming the equivalent of “Come on out, Nazarene! Come out and fight!” And the last scenes are a disappointing anticlimax that raise once again the ancient question: Why is evil always so much more colorful than good in the movies?