The insidious, devastating effects of capitalism, colonialism, and the Church—the three big Cs—on indigenous communities are considered by director Maya Da-Rin in her quietly ruinous “The Fever.” “Quiet” does not mean “gentle.” Barely anyone in “The Fever” raises their voice or a hand to anyone else, nor is there any sort of grand moment when a character bravely speaks out against any of the big Cs. This is a film shaped by moments of silence, and by the realization of what we steadily lose every day: the time spent commuting to a job that doesn’t value its workers, the natural world destroyed by companies and corporations, the dignity stripped from us by casually cruel colleagues, neighbors, family, or friends. When progress stops feeling like progress is what Da-Rin captures in “The Fever,” and fantastic lead actor Regis Myrupu is a conduit for a calamity that builds and builds.

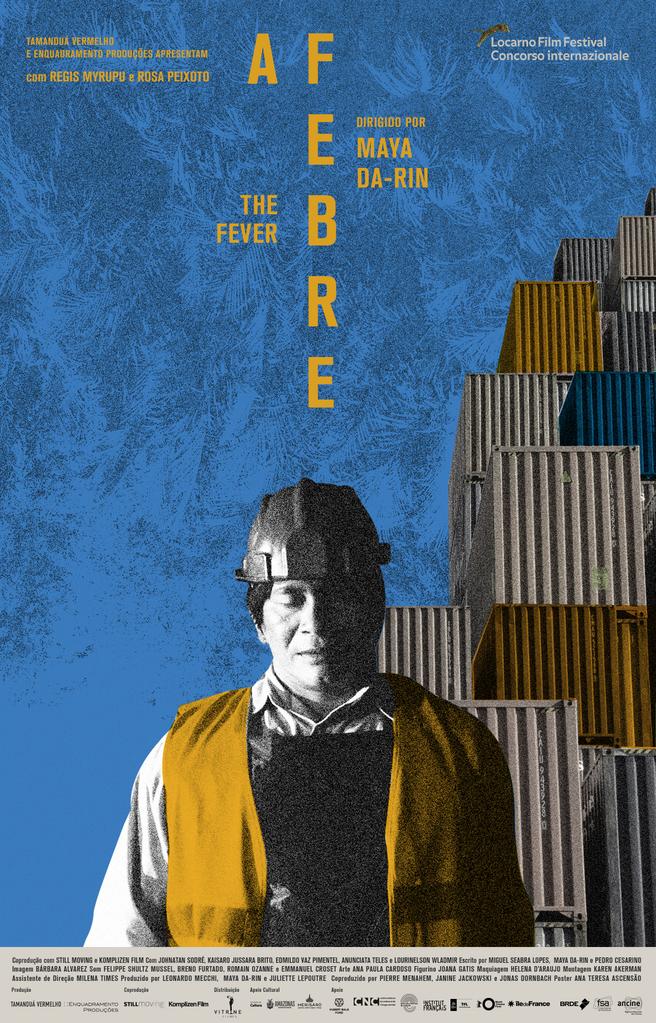

Da-Rin has spent years crafting films focused on the clash between industrialism and traditionalism in the Amazon rainforest, and the idea for “The Fever” arose out of the documentaries “Land” and “Margin.” “The Fever” is set in Manaus, the capital city of the Brazilian state Amazonas and the center of the Amazon Rainforest. In the late 1960s, the movie’s press notes explain, Brazil established Manaus as a Free Economic Zone, and along with the construction of new factories came stores, supermarkets, and open-air markets. The Manaus cargo port is a major stopping point for companies transporting goods not just to South America but around the world, and the shipping containers all stacked on top of each other like so many Lego blocks form a labyrinthine maze.

But the increased economic opportunity, as always, is double-edged. Manaus hasn’t grown with its population, resulting in urban sprawl and inadequate transportation and health care, and yet more people—in particular indigenous migrants relocating from villages destroyed by sustained deforestation—make it their home every day. That’s exactly what 45-year-old Justino (Myrupu) did. A member of the indigenous Desana people of the Upper Rio Negro region, which runs along the Brazil/Colombia border, he moved to Manaus decades ago to get a job. He started as a construction worker, then worked as a factory employee, then became a watchman, and for the past 20 years he’s held down employment as a security guard at the Manaus port.

Every day is the same. Long hours on his feet watching the containers, walking through the narrow pathways left between them, and checking that they’re locked. He barely speaks to anyone else. He carries a gun and wears a bulletproof vest, which hint at the possibility for violence, but he seems to spend most days totally alone. He takes two buses to get from his small one-room home, where he lives with his youngest daughter Vanessa (Rosa Peixoto), to the port; is it any wonder he begins to nod off at work? Da-Rin’s unfussy camerawork captures the contrasts Justino experiences in these myriad spaces. At the cold port, where Justino is practically an automaton, and in the packed bus, where Justino naps alongside other workers forced into similarly gruelingly long commutes. In his house, where various plastic bottles hold clean water and a hammock in which Justino sleeps hangs from the ceiling, and in the rainforest only steps away, from where Justino cuts down bunches of bananas for his family to eat as a baked treat. These are two worlds in Manaus, and Justino travels—or perhaps is trapped—between them.

As “The Fever” continues, Justino’s ordered life begins to show little cracks. A literal one in his home’s cement foundation; if Justino doesn’t repair it, the home could be washed away in one of Manaus’ many rainstorms. At work, where he receives a formal HR citation for his exhaustion, and where his new coworker Wanderlei (Lourinelson Wladmir) thinks that racist jokes calling Justino the “Indian,” “squinty eyes,” and “tame” are perfectly fine. With Vanessa, whose acceptance into medical school in Brazil’s capital city Brasília means she’ll soon be leaving Justino alone. And in a fantastical subplot that nods to the Desana people’s belief in the relationships between humans, animals, and the natural world, the increasingly feverish Justino begins to wonder if he’s being haunted by something—some kind of dark, amorphous being that has been terrorizing the neighborhood. News briefs interrupt Justino and Vanessa’s meals, with grim-faced reporters reporting on the latest killed animals. Perhaps it’s that creature who is responsible for the mysterious rustling noise Justino keeps hearing in the underbrush, and for the footsteps he hears following him home.

Da-Rin and cowriter Miguel Seabra Lopes strike a solid balance with a script that doesn’t overemphasize any one reason for Justino’s growing sense of placelessness, but pays attention to how many dehumanizing factors can work in tandem. Vanessa, who works at a local health clinic treating indigenous people who speak dying languages and who travel from dying villages, sees what is happening to people in her community and thinks that becoming a doctor could at least allow her to help those who need it. But what she doesn’t quite grasp is how much her father might be one of those people.

“The Fever” is deliberate in its escalation. Justino has a horrible meeting with the port’s HR rep, who in one breath offers sympathy for his wife’s recent death and in another condescends to him regarding his retirement savings. (Her “It’s only what’s on the books that counts, not how long you’ve been alive” is a moment cutting enough for Ken Loach.) It’s in how Justino looks at a religious service led by missionaries in the village, who encourage the congregants to sing the hymn “New days are coming/These days we must be happy/God’s time is coming,” and then the surety with which he walks away. And most provocatively, in two scenes when Justino ventures into the rainforest, as its denseness and strangeness almost seem to wipe him of the identity he’s long associated with this place. He becomes unrecognizable to others, and perhaps even unrecognizable to himself. What about him has become lost in all these years away? What can never be regained?

The script is sometimes a little too on the nose, like when that same HR rep calls Justino’s indigenous heritage “your condition,” and when Justino and his brother tell their children about how different it was growing up in the village (“If you had to work the fields, you’d cry … You’d run away”). “The Fever” could have been a little clearer regarding the Desana people’s cosmological beliefs so that certain elements of Justino’s fear and trepidation hit harder. But Myrupu’s performance is difficult to resist: His natural physicality benefits scenes that require Justino to creep and skulk, his sly humor adds an obvious edge to exchanges with other characters who treat him like an alien, and his vulnerability strengthens the relationship he has with Peixoto. “Exotic invading species can adapt so well to a new ecosystem that they dominate the environment and end up eliminating the native species,” a reporter says in “The Fever.” Da-Rin’s film is an urgent portrait of a kind of life our desperate sprint toward modernity has incorrectly deemed as lesser-than.